Varieties of Far Rights

The global surge of far-right political parties and social movements has brought about a “reactionary international” with its own organic intellectuals. At its regular gatherings, participants have the opportunity to share their experiences, hone their rhetoric, borrow from each other’s programs, and define common causes. Solidarity and emulation notwithstanding, differences between the various strands of illiberalism should not be overlooked. While often compelled to cohabitate, promoters of a nativist welfare state financed by customs tariffs and purged of its non-native beneficiaries do not see eye to eye with libertarian slashers of state agencies. Similarly, nostalgia for traditional hierarchies does not necessarily mesh with a defense of the “little guy” subjected to the yoke of arrogant technocratic elites

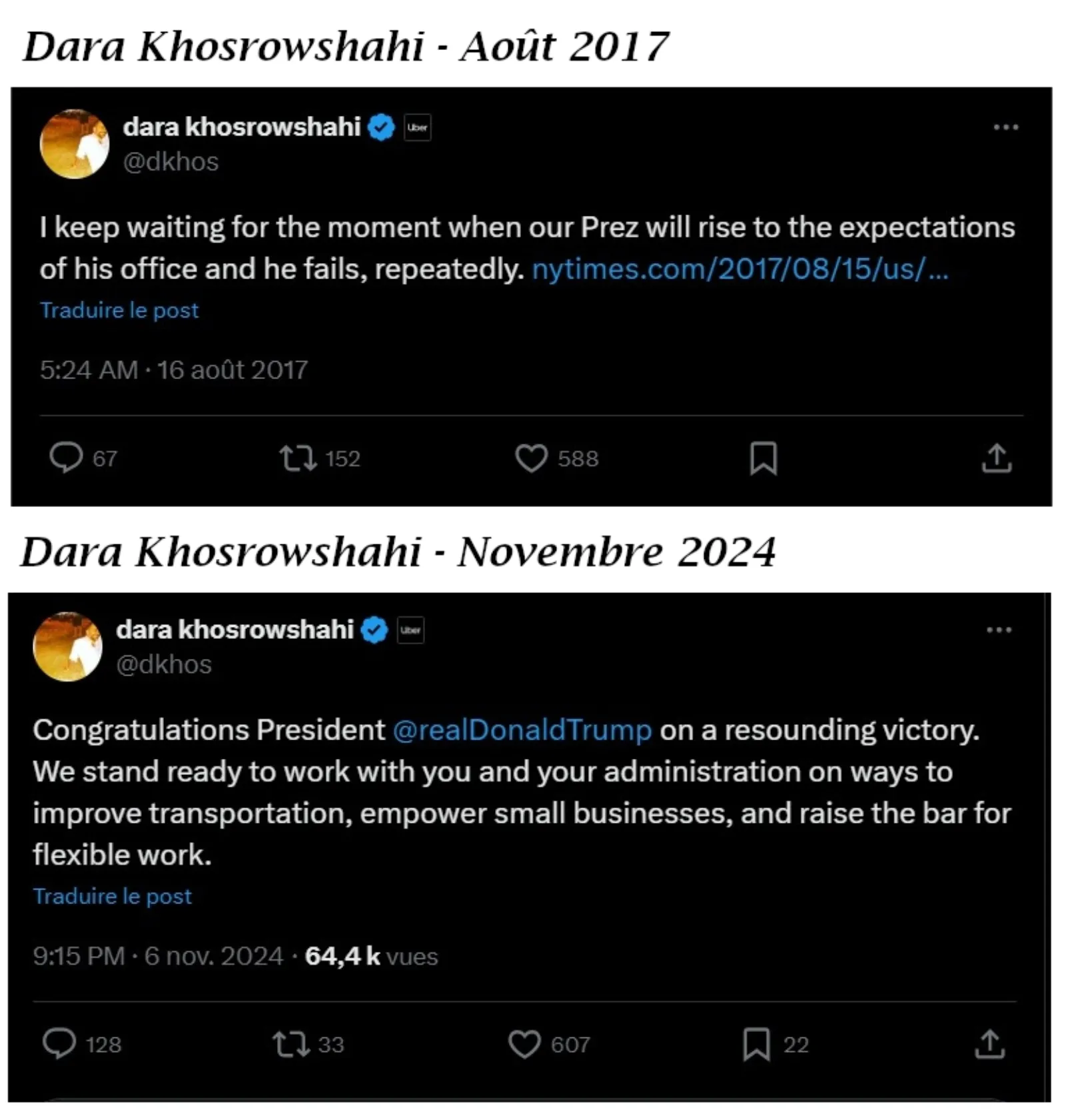

The promise of national regeneration through sorting and cleansing undoubtedly serves as a powerful glue for all the formations occupying the far-right of the political spectrum. However, the criteria for selecting parasitical groups tend to vary from one country to another, and also from one political sensibility to another. Foreign-born minorities may not all be treated equally - as shown by the Spanish far right's preference for immigrants from the former colonial empire. Sometimes, xenophobia may even conflict with racism - as illustrated in the US by the dispute between MAGA's nativist wing and IQ-obsessed tech oligarchs over whether to offer visas to ‘highly qualified’ internationals.

Far-right imaginaries also vary according to the importance they attach to the religious legitimization of their programs and the phobic obsession with matters of gender and sexuality. In France, for example, the National Rally seeks to legitimize Islamophobia by trumpeting its allegiance to secularism and castigating Muslims for their alleged mistreatment of women and homosexuality. In Italy, by contrast, the damage supposedly caused to masculinity and the traditional family by feminism and LGTBQI+ activism features prominently in the moral panics stirred up by so-called post-fascists.

Equally worthy of attention is the conquest of state power by the far right, which follows different paths according to the institutional and national context. Where a two-party system is the norm, as in the United States, the takeover is necessarily premised on the capture of one of the traditional parties. In countries where the political field is more fragmented, as is generally the case within the European Union, forming a coalition with traditional neoliberal parties, whether conservative or centrist, is typically how their illiberal counterparts manage to access governmental responsibilities.

Despite their acute awareness of belonging to a large family and their willingness to pool their resources, the members of the reactionary international are not all cut from the same cloth. It is therefore important to stress and analyze their distinctive features, for at least two reasons: to figure out how they adapt their strategies and doctrines to the constraints of their specific environment; and to understand how their mode of managing commonalities and differences contributes to their overall growth.

How Italy Lost its Antifascist Compass

Interview conducted on 13 October 2025

“The movements we're dealing with today in Italy, the cradle of fascism, never disappeared. There is no point in talking about the return of fascism; it has always been there.”

The Manufacture of Denial

Interview conducted on 24 September 2025

“If you take away the agencies that play a crucial role in measuring climate change, you don't even have to deny science anymore. You just destroy it. There is something particularly aggressive and tragic about all this. It's really moving into Orwellian territory.”

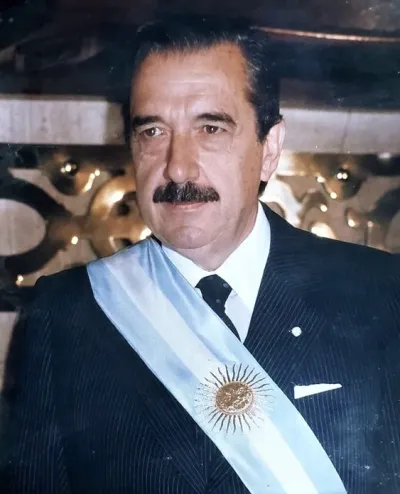

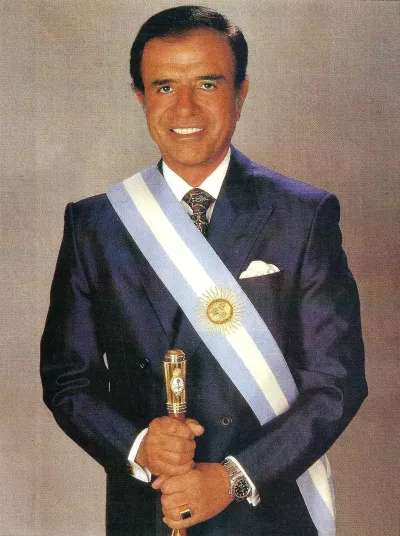

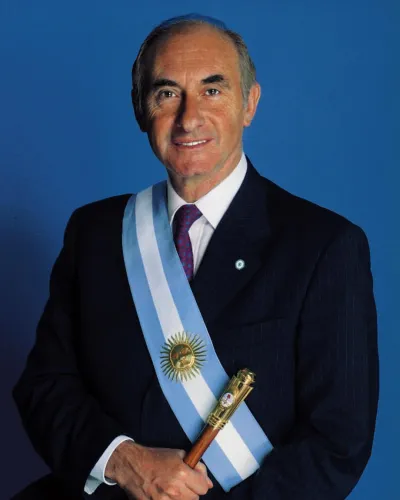

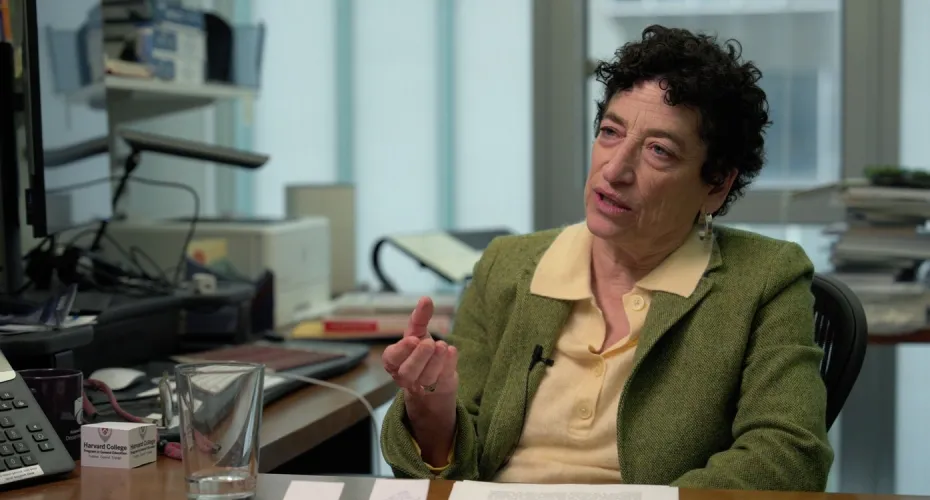

THE ARGENTINIAN LABORATORY

Interview conducted on 01 April 2025

"Milei presented himself as the final outcome of the representational crisis of the system."

REVOLUTIONARY CONSERVATISM

Interview conducted on 14 March 2025

"There has always been a kind of anti-capitalism of the far right. That's true of all far right. What's distinctive about the American version is that there's a current within it that is deeply libertarian, deeply attached to the idea of free markets. And this produces a particular kind of anti-capitalism or pseudo anti-capitalism, because they're attacking one faction of capitalism to elevate another, which is their own."

POSTDEMOCRACY IN AMERICA

Interview conducted on 23 February 2025

“Race has always been used, in American politics, as a battering ram against every public good, any redistributive impulse, any idea of collective freedom or social freedom. If you go in there with race, saying that what you’re doing is protecting white people from black people, then you end up protecting capitalists from social provision.”

LATE NEOLIBERALISM

Interview conducted on 01 February 2025

"If you think about neoliberalism as a kind of ongoing project to protect capitalism from democracy, then the enemies and the threats to capitalism transform from decade to decade."

Portraits

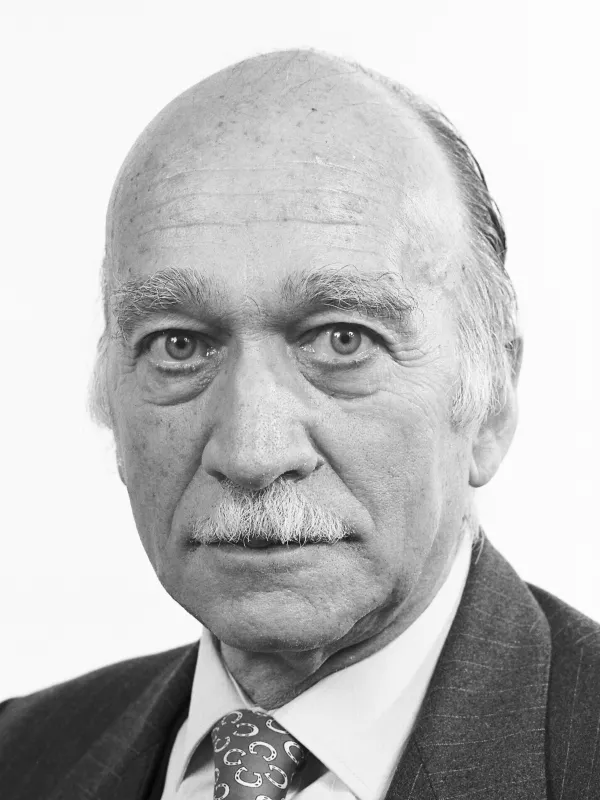

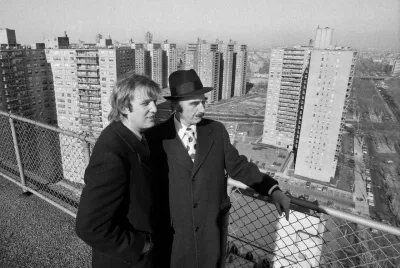

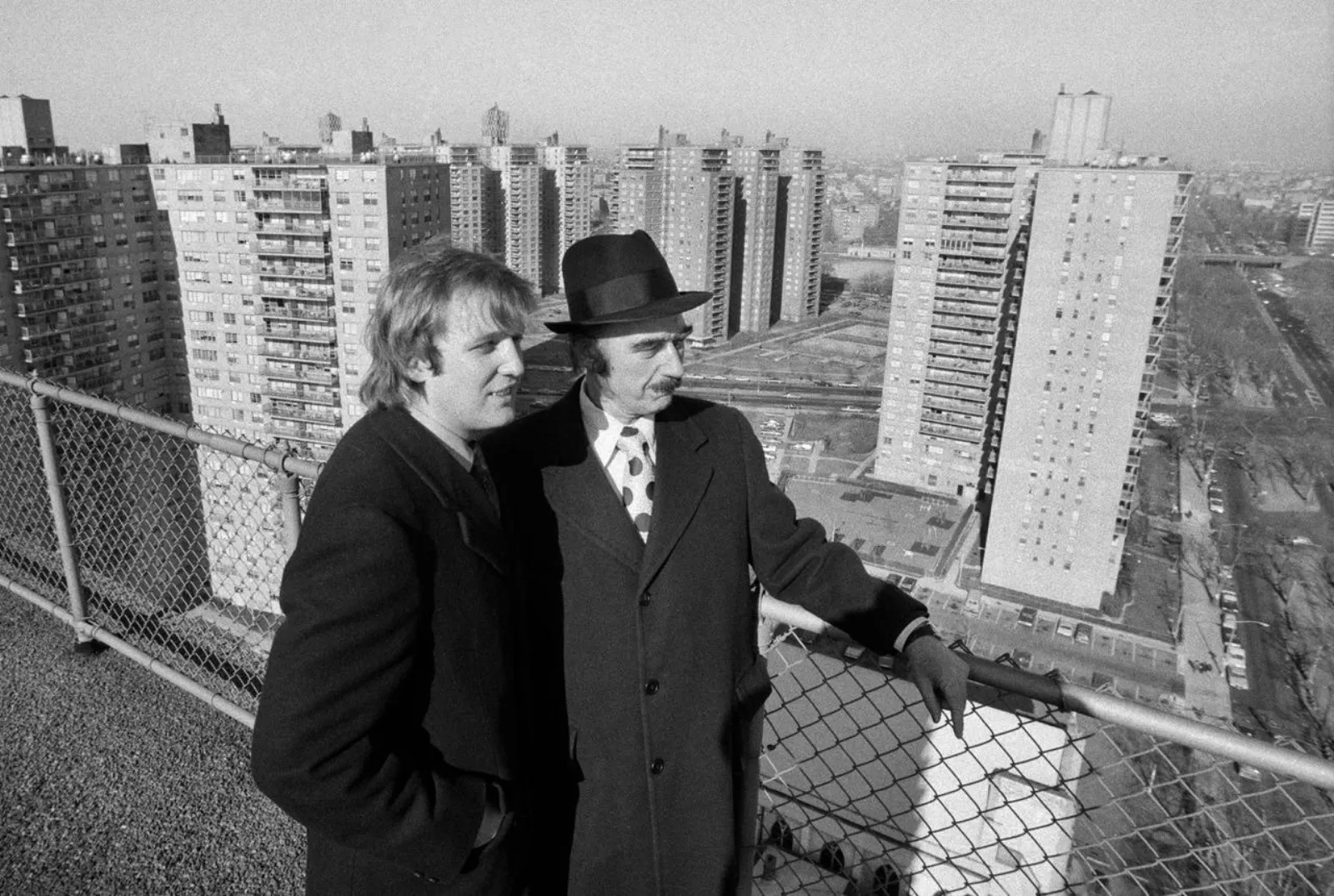

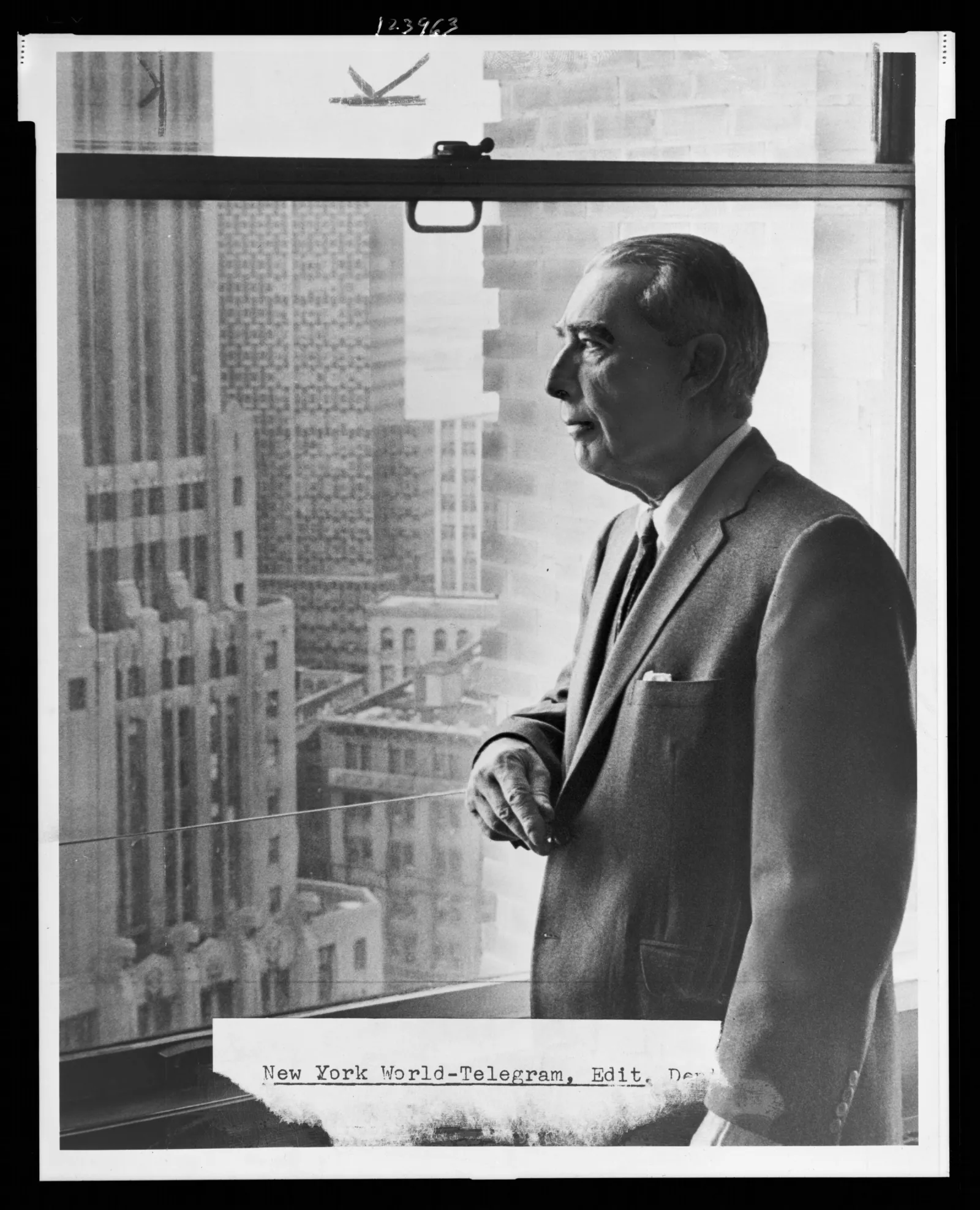

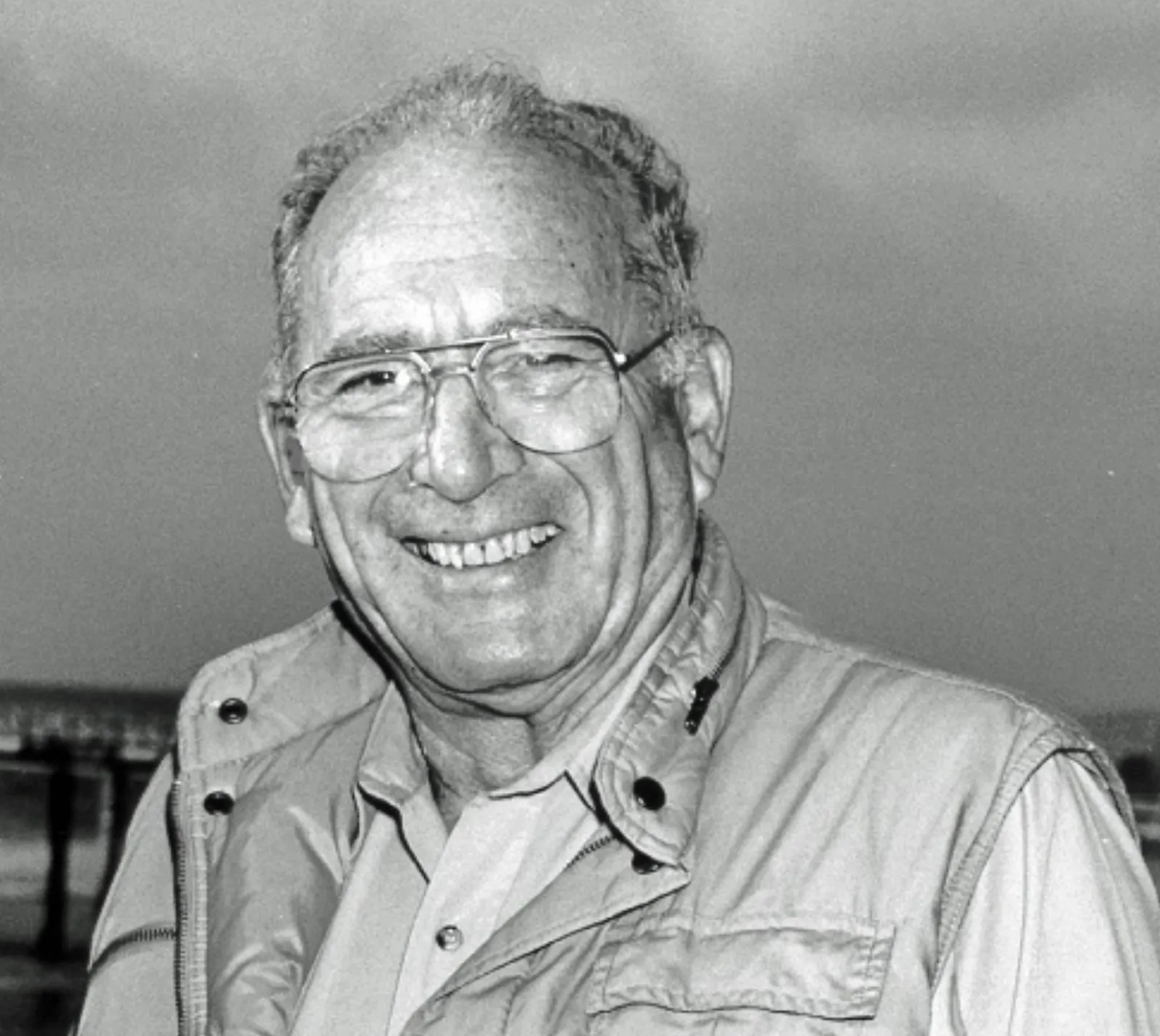

Giorgio Almirante

In 1946, when supporters and associates of Benito Mussolini founded the neofascist party Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI), they chose a tricolor flame as an emblem. While the most significant symbols of fascism had, until then, been the fasces or the imperial eagle, Giorgio Almirante, one of the co-founders who would become MSI’s long-time president, saw the flame as a powerful image: Mussolini’s spirit escaping from his coffin. He succeeded in imposing the symbol to galvanize his troops and engrave in their minds the idea that fascism should remain “the ultimate goal” (‘il traguardo’) he had helped to launch.

During the war, Almirante had been a theorist of racism and a propagandist of anti-Semitic “racial laws”. Throughout his entire parliamentary career, and until his death in 1988, he shamelessly asserted that his Movimento Sociale Italiano had been conceived as a party of "fascists within a democracy”. His ambition was simply to adapt an old cause to the realities of the new era. Responding in 1982 to an exhortation by the founder of the Italian Radical Party, Marco Pannella, to clarify his party’s relationship to the fascist legacy, Almirante stated: “[The MSI] represents fascism as freedom, not as a regime—that is, as a movement, as a social tradition, as a synthesis of values”.

Under Almirante, the MSI was fiercely anticommunist and dedicated to an alliance with the monarchist right, which was unwilling to compromise with the “Constitutional Arc”. The party remained implicated in a range of conspiracy to overthrow the State and instigated terrorist acts until the 1980s. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Giorgio Almirante also activated his international neo-fascist networks. In particular, he was behind the creation of the National Front in France in 1972, advising members of the far-right Ordre Nouveau (New Order) movement on how to establish a party of “fascism with a smiling face”.

Initially a film critic and voice actor, Almirante later became involved in political journalism. He soon became editor of the newspaper Difesa della Razza (“Defense of the Race”) and in 1938 signed the Manifesto della razza (“Manifesto on Race”), which set out the racist measures implemented by Mussolini. The scribe then rose through the ranks in Sardinia and Libya, where he took part in the North African Campaign. When the Italian Social Republic was established in 1943, a puppet state and vassal of the Third Reich, Almirante followed the Duce to Salò. This earned him the position of chief of staff of the “Ministry of Popular Culture” headed by Fernando Mezzasoma during the last two years of the war. It was then that he demanded that his followers prepare for a “physical confrontation” with the partisans and that he himself became actively involved in this counter-resistance, on the side of the Lepontine Alps and in Tuscany.

When the MSI was founded in 1946, Almirante established the party headquarters at Via della Scrofa 39, which would later become a legendary address for the Italian right, just like Via delle Botteghe Oscure for the communists, Piazza del Gesù for the Christian Democrats, and Via del Corso for the socialists. In addition to the management office, it also housed the editorial office of the newspaper Il Secolo, a sort of central organ for the neo-fascists. Silvio Berlusconi with Forza Italia and then Giorgia Meloni and her Fratelli d’Italia later took up residence there. A leading figure of the Italian far right during the First Republic, Almirante has enjoyed a posthumous revival since the turn of the century as an idol of transalpine neo-fascists. Under Berlusconi’s leadership, when the restoration of fascist heritage and monuments began in Italy, some municipalities even went so far as to rename streets in honor of Giorgio Almirante and other prominent figures of historical fascism. More recently, Almirante was also celebrated by Meloni, who claimed in her autobiography Io sono Giorgia (“I am Giorgia”), published in 2021, to have “taken over from Giorgio Almirante,” her long-time political idol.

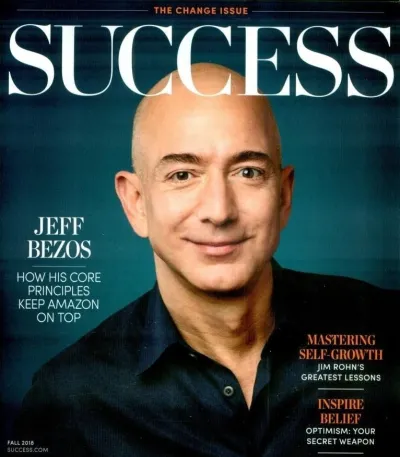

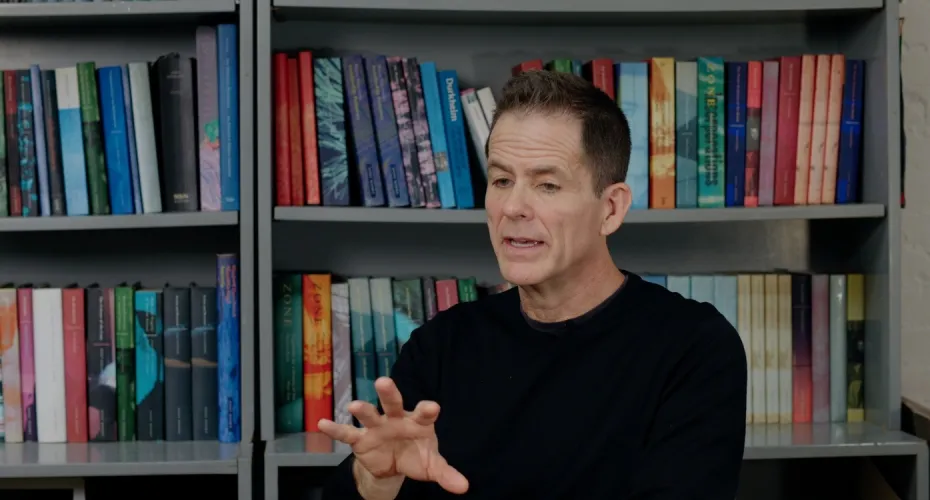

Marc Andreessen

Born in 1971, Marc Andreessen is a software engineer and a Silicon Valley investor. In 1993, he and Eric Bina programmed NCSA Mosaic, the first widely used web browser with a graphical user interface, which would later become the software of Netscape Communications. In 2009, after creating and working with a number of successful software companies, Andreesen co-founded the Silicon Valley venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, commonly referred to as a16z, with Ben Horowitz. Through a $4.5 billion fund launched in 2022, a16z is currently the largest backer of the crypto industry.

Andreessen is a self-described libertarian and “techno-optimist”. In October 2023, he published the “Techno-Optimist Manifesto” on the a16z website, in which he presents his vision of the future that technology will make possible. Inclusive statements notwithstanding - “We believe technology is universalist. Technology doesn’t care about your ethnicity, race, religion, national origin, gender, sexuality, political views, height, weight, hair or lack thereof” - Andreessen’s manifesto celebrates the advent of a world in which technology and unregulated markets will provide opportunities for everyone.

A great promoter of the democracy-free zones that Quinn Slobodian writes about in Crack-Up Capitalism, Andreessen made his libertarian dream come true when he co-founded Próspera with Peter Thiel and OpenAI CEO Sam Altman. Próspera is a private city in Honduras where unregulated businesses can thrive.

Andreessen and Horowitz have been key players in Silicon Valley’s gradual shift of political allegiance to the Republican Party. Although he does not hold a title in the Trump administration, Andreessen has been instrumental in the framing of Trump 2.0. In particular, he has been deeply involved in the selection of candidates seeking to implement the program-slashing and personnel-firing mission of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE). Prior to the 2024 presidential election, Andreessen was one of Trump’s top campaign donors to the Right for America Super PAC, contributing $4.5 million personally and $7 million through a16z.

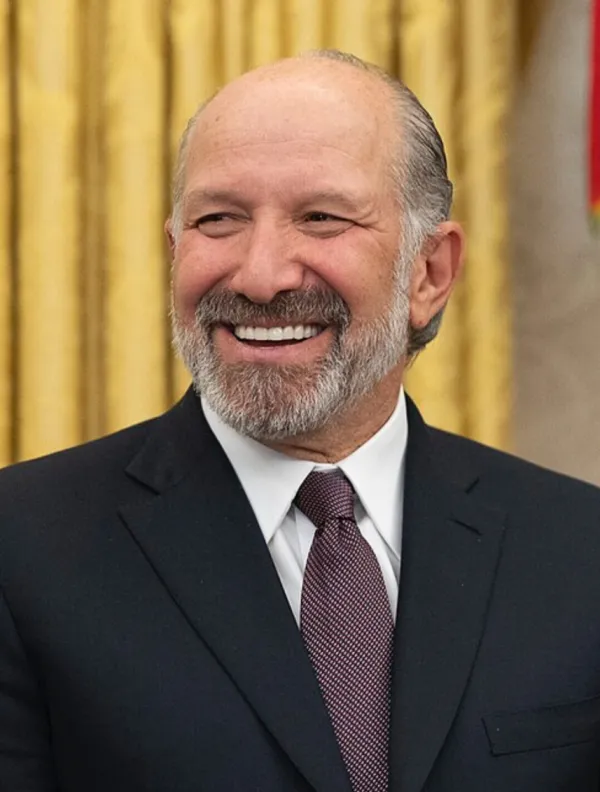

Howard Lutnick

Howard Lutnick is Trump’s Secretary of Commerce. Following his confirmation, he stepped down as chairman and CEO of Cantor Fitzgerald and the BGC Group, an investment banking and financial services firm. Lutnick himself is a fervent crypto advocate and Cantor Fitzgerald is the bank of Tether, the world’s most important stablecoin.

A major contributor to Trump’s campaign, the Secretary of Commerce has known the U.S. president for many years - even appearing on a 2008 season of The Celebrity Apprentice. He calls his long-standing relationship with Donald Trump his “superpower” and is known for his staunch loyalty to his boss but also for being the inspiration behind some of Trump’s wildest ideas – including the takeover of the Panama Canal and the introduction of a “Gold Card” visa that would confer legal residency to foreigners – even if they are not Afrikaners – at a cost of $5 million.

As Secretary of Commerce, Lutnick, who resents Scott Bessent for getting the job he really wanted, has been the main champion of liberational tariffs – alongside Peter Navarro. How he has defended Donald Trump’s quest for what he sees as fair trade, however, is reminiscent of Sigmund Freud’s “kettle story” – i.e., a man accused by his neighbor of having returned a kettle in a damaged condition claims first that it was undamaged when he returned it, second that it was already damaged when he borrowed it, and third that he had never borrowed it in the first place. Likewise, Lutnick has successively (1) denied that tariffs would raise prices for US consumers, (2) argued that a period of inflation and even a recession were unavoidable sacrifices, and (3) that most if not all US partners would soon make a deal with the Trump administration, making tariffs unnecessary.

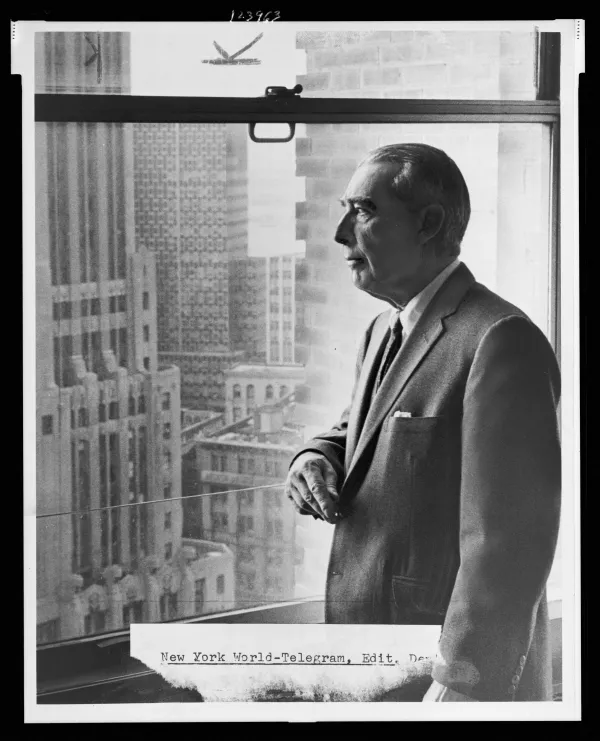

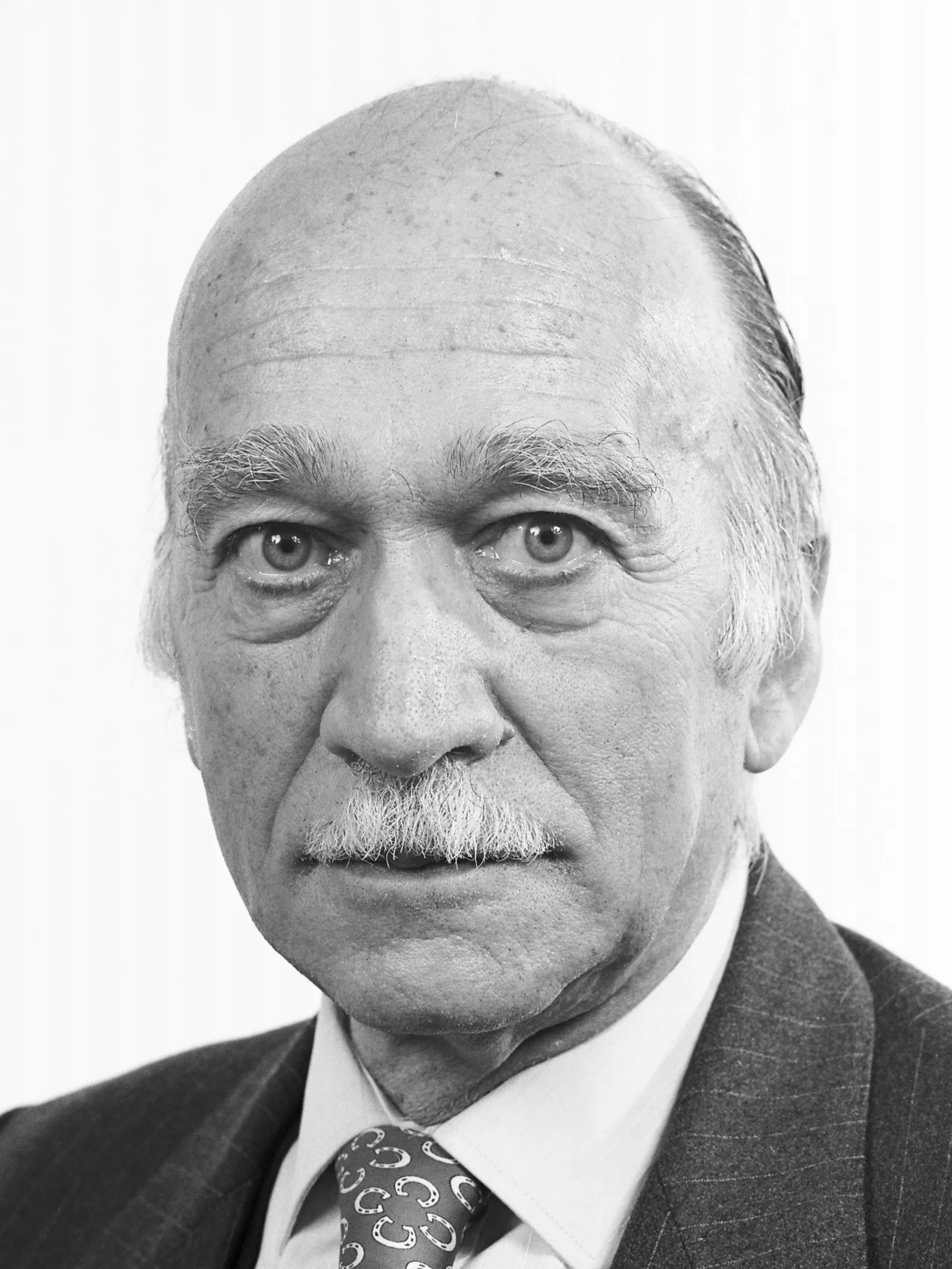

Adolf Berle

In 1943, a New Yorker profile of Adolf Berle ended with the following statement: “It is a big job to plot the future of the world, but Berle gives many onlookers the impression that he is up to it.”1 Born in Boston in 1895, the future member of Franklin Roosevelt’s first “Brain Trust” started off as a child prodigy. He entered Harvard College at the age of 14 and graduated from the Law School at 21. After the end of World War I, Berle joined the American Delegation to the Paris Peace Conference – where he met John Maynard Keynes. Like the British economist, he was appalled by the terms of the resulting Treaties and made his disappointment public. Back in the US, he became a corporate lawyer, contributed regularly to liberal magazines such as The Nation and The New Republic, and started teaching corporate law at Columbia University in 1927.

In the wake of the 1929 financial crash, Berle embarked on what would be his major intellectual endeavor: The Modern Corporation and Private Property, coauthored with the economist Gardiner Means and published in 1932. In this epochal book, Berle and Means addressed the transformation of US capitalism that they were then witnessing. They showed how the rule of the “robber barons” – Andrew Carnegie, Thomas Edison, John D. Rockefeller, J.P. Mellon – had given way to the dominance of publicly traded corporations. These firms were as big as the so-called trusts of yore, but they were no longer in the grip of their almighty founders or, for that matter, of any owner. Each of them had myriads of shareholders – more than half a million in the case of American Telephone and Telegraph – which meant that the people in charge of these huge companies were their salaried managers and directors. Property and power were thus dissociated, a first in the history of capitalism according to Berle and Means.

For the authors of The Modern Corporation and Private Property, the fact that the fate of the American economy rested upon largely unaccountable managers was certainly a cause for alarm. At the same time, Berle and his coauthor were not inclined to turn back the clock: they shared neither the economist Joseph Schumpeter’s nostalgia for the era of autocratic captains of industry nor justice Louis Brandeis’s conviction that the only way to ward off the hegemony of corporations consisted of using antitrust legislation to break them up. The task at hand, Berle and Means argued, was not to restore the privileges of private capital, whether owned by tycoons or small entrepreneurs, but to harness the power of publicly traded companies for the public good. Rather than empowering shareholders or dismantling huge corporations, the way to treat excessive managerial power was to regulate it. In other words, both the danger to democracy and the potential for prosperity represented by big business called for a bigger government to intervene on behalf of workers, consumers and other stakeholders of the largest firms.

Soon, Berle would be in a position not only to advocate for State regulations but to implement them. After meeting Franklin Roosevelt in 1932, he actively took part in the Governor’s presidential campaign – writing his famous “Commonwealth Club Address”, which delineated the economic program of the first New Deal. Once his candidate was in the White House, however, Berle declined the offer to take a cabinet post, choosing instead to remain an informal advisor in what would be called the president’s “Brain Trust”. His influence on the administration’s agenda rapidly translated into three major economic reforms: the separation between commercial and investment banking (the Glass-Steagall Legislation of 1932), the federal insurance of wage earners’ bank deposits and the regulation of corporate stock and bond offerings. Like Keynes albeit with different tools, Berle’s purpose was to tame capitalism and the early years of the New Deal certainly advanced that goal.

However, after the Supreme Court declared the National Recovery Administration unconstitutional, Berle lost some of his clout. Still, he remained influential enough to be appointed as Assistant Secretary of State for Latin American Affairs in 1939 and to draft Roosevelt’s declaration of war message to Congress in 1941. After losing his cabinet post in 1944, Berle was made US ambassador to Brazil before leaving government service altogether in 1946. He remained an informal advisor to several politicians, however – from Adlai Stevenson to Nelson Rockefeller and John Kennedy – as well as a tireless publicist both for the New Deal compact that he had contributed to shaping and, because of its success, for the beneficent role of the US in the world. Hence Berle’s unflinching support for American imperial interventions, from Latin America to Vietnam.

Five years after his death, in 1971, Berle’s vision of the corporation came under a fatal attack. In an article entitled “Theory of the Firm”, Michael Jensen and William Meckling echoed the worry raised The Modern Corporation and Private Property that the separation of ownership and control distinctive of modern corporate governance licensed salaried directors to run large companies as they pleased. How the two disciples of Milton Friedman dealt with that problem, however, ran against the taming of capitalism advocated by Berle and Means: instead of taking the artificial personhood of the public corporation for granted and checking managerial power with federal regulations, Jensen and Meckling claimed that managers were nothing more than agents hired to do the bidding of the firm’s shareholders. In their view, ceasing to recognize the corporation as an autonomous entity was a decisive step toward reconciling ownership and control. As decisive as The Modern Corporation had been for the New Deal, the publication of “Theory of the Firm” can be perceived as a turning point leading to our current “gilded age” and its new “robber barons”.

1 Quoted by Nicholas Lemann in “Institution Man”, the first chapter of his book Transaction Man: The Rise of the Deal and the Decline of the American Dream (New York, Farrar Straus and Giroux), 2019. https://business.columbia.edu/...

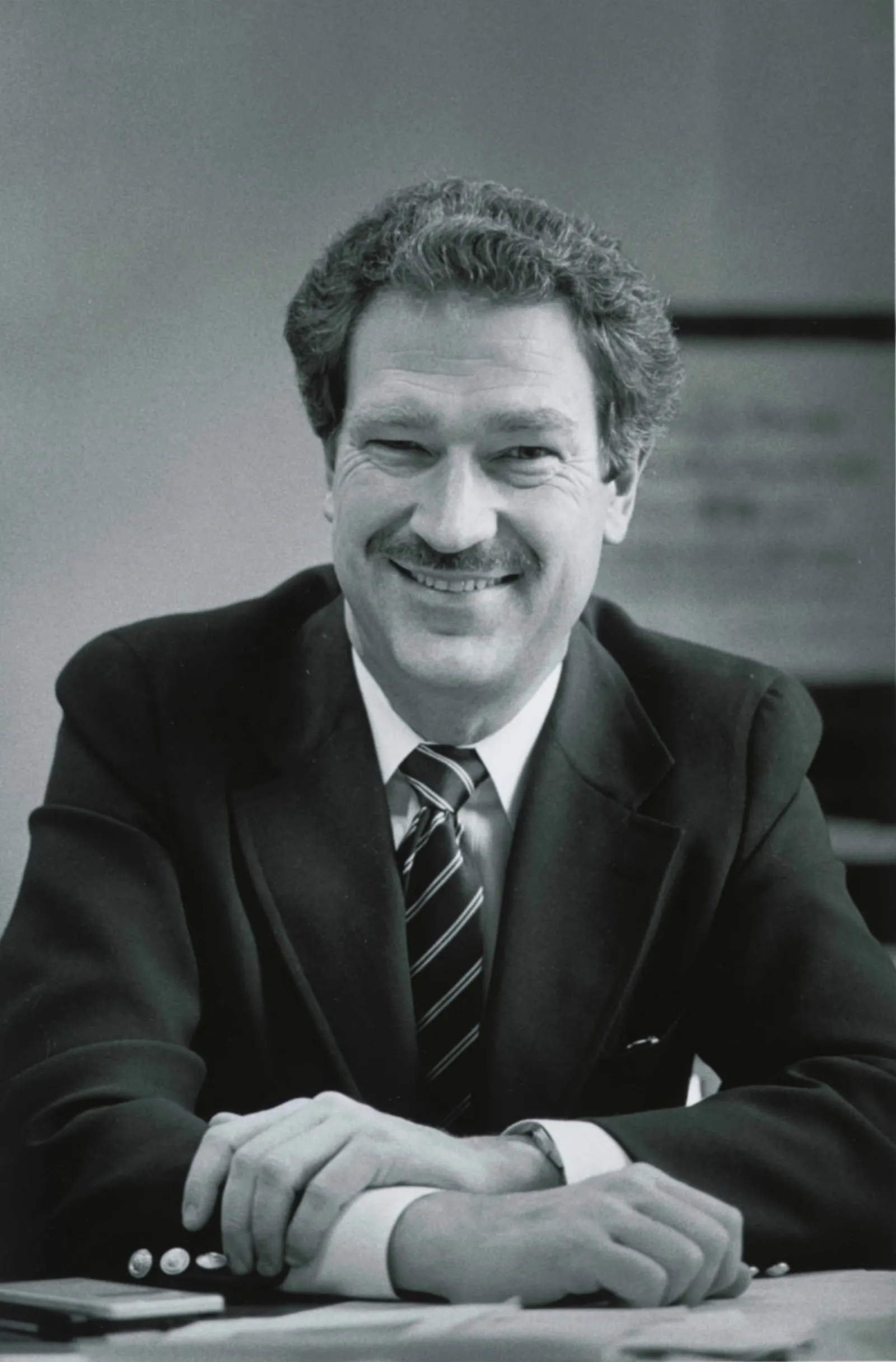

Robert Mercer

Born in 1946, Robert Mercer is a computer scientist who made his fortune working as a financial analyst for the very successful hedge fund Renaissance Technologies. In 2009, he became its co-CEO, but had to step down from this role and renounce his board seat in 2017, after the backlash over his involvement in the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

In 2013, the billionaire bought SCL Group, a company that specialized in analyzing Internet data. While renaming the company “Cambridge Analytica” to give it the appearance of a legitimate business, he completely redefined its activity. Through the analysis of Facebook profile data obtained without the informed consent of the 87 million targeted individuals, Cambridge Analytica deployed a large-scale covert advertising strategy adapted to the different psychologies and socio-economic factors of voters, to sway them to vote “Leave” in the Brexit referendum and to vote for Ted Cruz and Donald Trump in the 2016 U.S. election cycle. Because he was funding a private company, Mercer was able to circumvent campaign laws, avoid political fallout and potential legal action related to data acquisition, while having a major impact on these political votes, that is until the story broke out in May 2017.

Mercer has also influenced politics through donations to conservative and libertarian organizations and PACs. He and his daughter, Rebekah Mercer, coordinate their political contributions through the Mercer Family Foundation, which they established in 2004 and which she runs. They have given millions to the Heritage Foundation – Rebekah has been on its board of trustees since 2014 –, the Federalist Society, the Citizens United Foundation (from 2011 to 2015), the conservative anti-Left Media Research Center and the libertarian and climate-skeptic Heartland Institute, among others.

They have also co-founded and invested at least $10 million in Breitbart News, a major far-right media outlet. They have promoted the ideas and career of Steve Bannon since the beginning of the 2010s – Trump met his political adviser through the Mercers. Their donations allow them to push their views on multiple levels – in the political sphere, in the media, but also at the grassroots level with their watchdog organization Reclaim New York, which encourages New Yorkers to signal excessive public spending. Their duo dynamic and the similarity of the recipients of their donations have earned them comparisons to the Koch brothers.

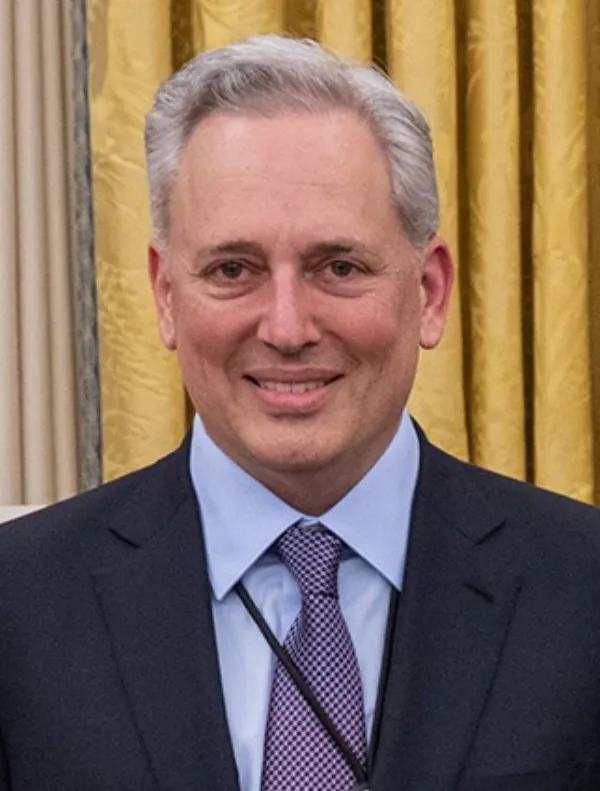

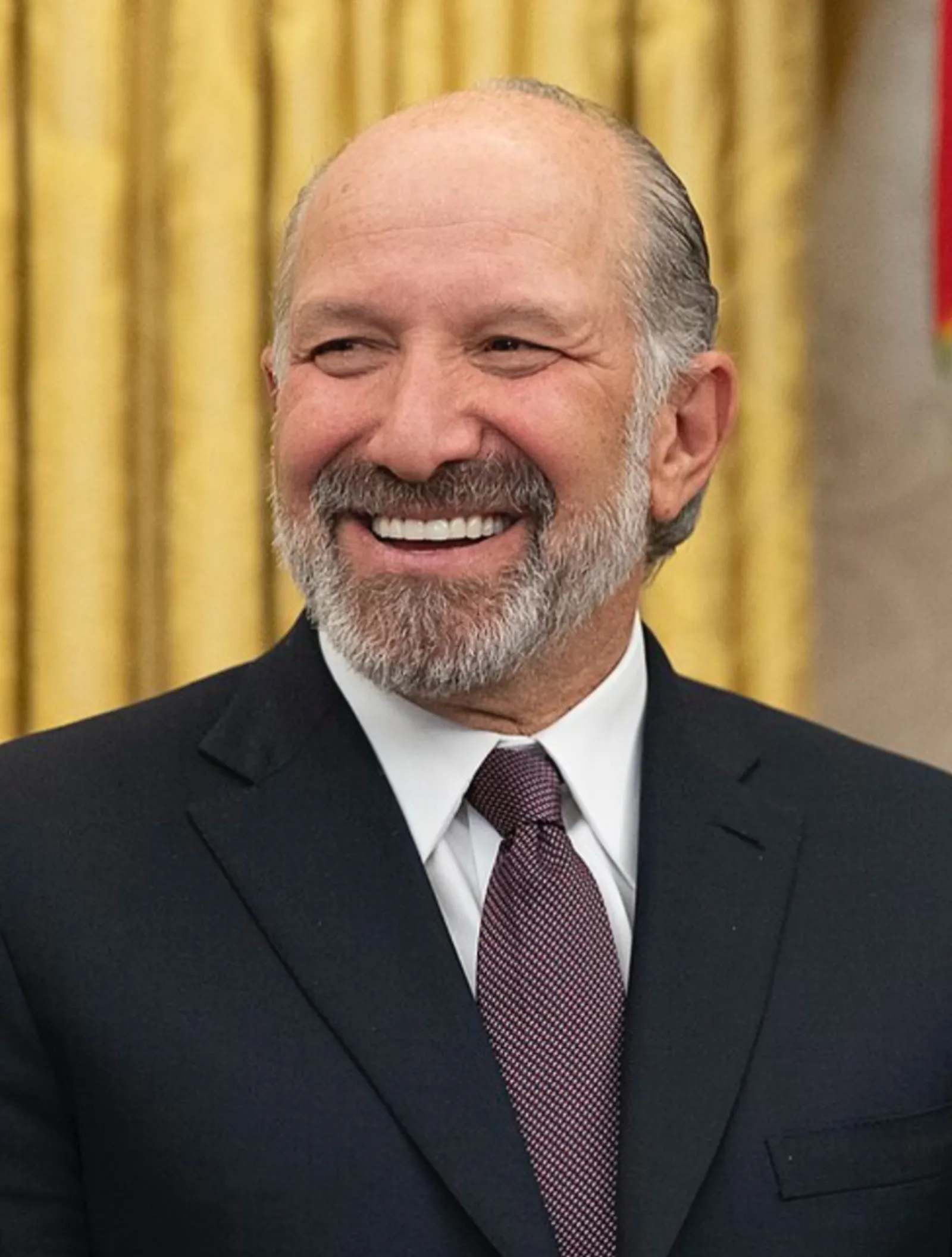

Scott Bessent

Scott Bessent, who currently serves as Donald Trump’s U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, has no other background in government than the fundraiser he organized for Al Gore in 2000. As a hedge fund manager, however, Bessent definitely has some experience with governments, since he can be credited with “breaking” the Bank of England, by betting against the British pound, back in 1992. At the time, the man who is now Trump’s appointee was a partner at the Soros Management Fund and thus an associate of George Soros, whose philanthropic endeavors figure among the main targets of MAGA’s anti-woke campaigns and whose name is arguably the main code-word for MAGA’s anti-semitic sentiment.

After leaving the Soros management Fund, Bessent co-founded the Key Square Group in 2015 and started embracing the libertarian causes dear to the hedge fund community more wholeheartedly. By 2024, he was one of Donald Trump’s biggest financial backers, donating $1 million to the MAGA Super PAC and another $100,000 to Right for America, another Trumpist Super PAC. He also hosted two fundraisers for Trump, one at his home in Greenville, South Carolina, which raised nearly $7 million and one in Palm Beach, Florida, which raised $50 million.

At his nomination hearing, Bessent praised the fiscal policy that he was appointed to implement and, despite not being cut out for the part, tried his best to give it a populist ring: “If we do not renew these tax cuts,” he warned, “we will be facing an economic calamity, and as always with financial instability that falls on the middle and working class people.”

Though visibly uncomfortable with Donald Trump’s tariff frenzy on “Liberation Day”, Bessent has quietly worked at reconciling his boss’s mercantilist views with Wall Street’s preferences. Hence his carefully crafted speech at the IMF Spring meeting on April 23, 2025, where he sought to reassure US partners by telling them that the administration’s purpose was to reform rather than destroy international institutions like the IMF and the World Bank: “America First does not mean America alone,” he asserted.

At the same time, however, Bessent made sure to remind his audience that the time had come for the IMF and the World Bank to “step back from their sprawling and unfocused agendas, which have stifled their ability to deliver on their core mandates.” What he meant was that the IMF should stop spending “disproportionate time and resources to work on climate change, gender, and social issues”, while “the World Bank must respond to countries’ energy priorities and needs and focus on dependable technologies that can sustain economic growth rather than seek to meet distortionary climate finance targets.”

Patrick Buchanan

According to his apologists, Patrick Buchanan is neither a racist nor an antisemite. He merely says racist and antisemitic things. As a former speechwriter and pundit, Buchanan has certainly resorted to words in order to make a living. Yet it would be unfair to suggest that, instead of being a true bigot, Buchanan was only playing one on TV.

Regarding race relations in the US, Richard Nixon, who employed him at the time, summarized his press secretary’s position as “segregation forever”. As for Jews, Buchanan’s statement on Treblinka not being an extermination camp squarely falls under the rubric of Holocaust denial – not to mention his kind words about Hitler. As fellow conservative commentator Charles Krauthammer once remarked, “(t)he interesting thing (about Buchanan) is how he can say these things and still be considered a national figure.”

One should add that even his most fervent advocates never tried to argue that Buchanan’s homophobic, xenophobic and sexist rants did not reflect his true self. At best, they might have claimed that the views he proffered on the AIDS epidemic – nature’s revenge on homosexual practices – immigration – an existential threat – and the role of women – “building the nest”, like “Momma Bird” – were less his own than those of the God he worships.

Born in Washington in 1938, Patrick Buchanan was raised as a traditionalist Catholic. His great-grandfather fought under General Robert E. Lee, and he remains a proud member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. A streetfighter and a bully in his youth – his family’s Jewish neighbors were his favorite target – “Pat” eventually matured, attending the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University and starting his journalistic career at the Saint-Louis Globe-Democrat.

In 1966, Buchanan was hired by Richard Nixon’s campaign team to write the speeches meant for the candidate’s conservative base. Among other accomplishments, he coined the phrase “Silent Majority”. After the election, he worked as White House assistant and speechwriter, kept his job during Nixon’s unfinished second term and remained faithful to his boss until the bitter end – he even urged the President to burn the Watergate tapes in order to stay in power.

When Gerald Ford took office, the new administration briefly considered making Buchanan the US ambassador to apartheid South Africa. However, because of his segregationist inclinations and his excessive enthusiasm about getting the job, the State Department eventually rescinded the offer. Temporarily retired from politics, Buchanan embarked on a long and successful career as a news commentator, first at NBC radio then on cable TV – where he successively joined NBC’s The McLaughlin Group and CNN’s Crossfire and The Capital Gang. In these popular shows, Buchanan was typically cast as the conservative voice pitted against a liberal counterpart.

The renowned pundit came back to the White House in 1985 as Ronald Reagan’s Communications Director. During his two-year tenure, Buchanan was instrumental in the organization of the President’s visit to the German cemetery of Bitburg, where 48 Waffen SS members were buried. While busy defending the Administration’s decision – in the face of widespread outrage – the Communications Director used his spare time fighting the deportation of suspected Nazi war criminals to countries of the Eastern bloc. For Buchanan, honoring the Wehrmacht’s sacrifice and frustrating the plans of “revenge-obsessed Nazi hunters” were two sides of the same mission – one that his great-grandfather would have surely condoned.

After leaving the Reagan administration and returning to punditry, Buchanan felt freer to embrace his favorite causes. In 1989, for instance, he paid yet another tribute to his Confederate ancestor by writing a column about the so-called Central Park Five case: in his article, he called for the public hanging of at least one of the Black teenagers falsely accused of having raped a white jogger.

At about the same time, Pat started encouraging his sister Bay, who had also worked for the Reagan administration, to pursue her “Buchanan for President” initiative. The siblings’ platform was two-pronged.

On the domestic front, Buchanan lambasted the open border policy promoted by the globalist wing of the Republican party – or at least by the contributors to the editorial pages of the Wall Street Journal: mass immigration from non-European countries, he warned, would fatally imperil the cultural and moral fabric of the United States.

With respect to foreign affairs, the former speechwriter argued that the closing of the Cold War should also mark the end of US military involvement throughout the world. Hence his staunch opposition to the Gulf War in 1990, which prompted his decision to run against George H.W. Bush two years later.

In the Republican primaries of 1992, Buchanan ran as the paleoconservative candidate: he challenged the incumbent President, whom he accused of harboring both a liberal and an imperialist agenda. Bush, Buchanan complained, had not only reneged on his “no new taxes” pledge: even more importantly, his administration had failed to curb immigration, to hinder women’s access to abortion and to suppress gay rights. Meanwhile, he added, the Jewish lobby and its neoconservative proxies were allowed to dictate the terms of America’s foreign policy.

Buchanan failed to win the nomination but still received almost a quarter of the votes. He also delivered his famous “culture war” speech at the Republican convention, where he claimed that America was in the grips of a decisive struggle for its own soul: the choice was between remaining “God’s country” or descending further down the liberal and multicultural path of moral decline. Though some commentators blamed the Republican defeat in the presidential election on the chilling effect of Buchanan’s oratory, the paleoconservative tribune persisted. After returning to Crossfire, he created a foundation called the American Cause to prepare himself for his next bid. He ran against Bob Dole, in the 1996 primaries, and was defeated once again.

After his second attempt, Buchanan began to despair of the Republican party, which he left in 1999. The following year, he ran as the candidate of the Reform party. While his campaign failed miserably, he inadvertently played a decisive role in George W. Bush’s controversial victory. In Palm Beach, Florida, about 2,000 ballots meant for Al Gore, the Democratic candidate, were mistakenly credited to him. Because the conservative Supreme Court rejected Gore’s request for a recount, his opponent was declared the winner in Florida, which gave him enough delegates to become President.

After 2000, Buchanan gave up on presidential politics and left CNN for MSNBC, where he was one of the few pundits who opposed Bush’s decision to invade Iraq. He also became even more overt in the defense of his other pet causes: one of his columns stated that the UK should not have declared war on Nazi Germany and his book entitled Suicide of a Superpower explicitly lamented the waning of white supremacy in America. Yet it was not until 2011 that MSNBC decided to end his contract.

Five years later, Donald Trump won the presidential election on a platform that largely echoed Buchanan’s. The latter had endorsed the MAGA candidate of course, though Trump’s success must have been bittersweet for the culture war veteran – who continued to write articles, mostly for Peter Brimelow’s white supremacist site VDARE, until 2023.

Similarities between their outlooks notwithstanding, the extent of Buchanan’s actual influence on the 47th President is open to debate. What his charmed professional life reveals, however, is the fact that long before Trump, Washington’s mainstream media and political establishment would already welcome an unapologetic segregationist and Hitler sympathizer as one of their own.

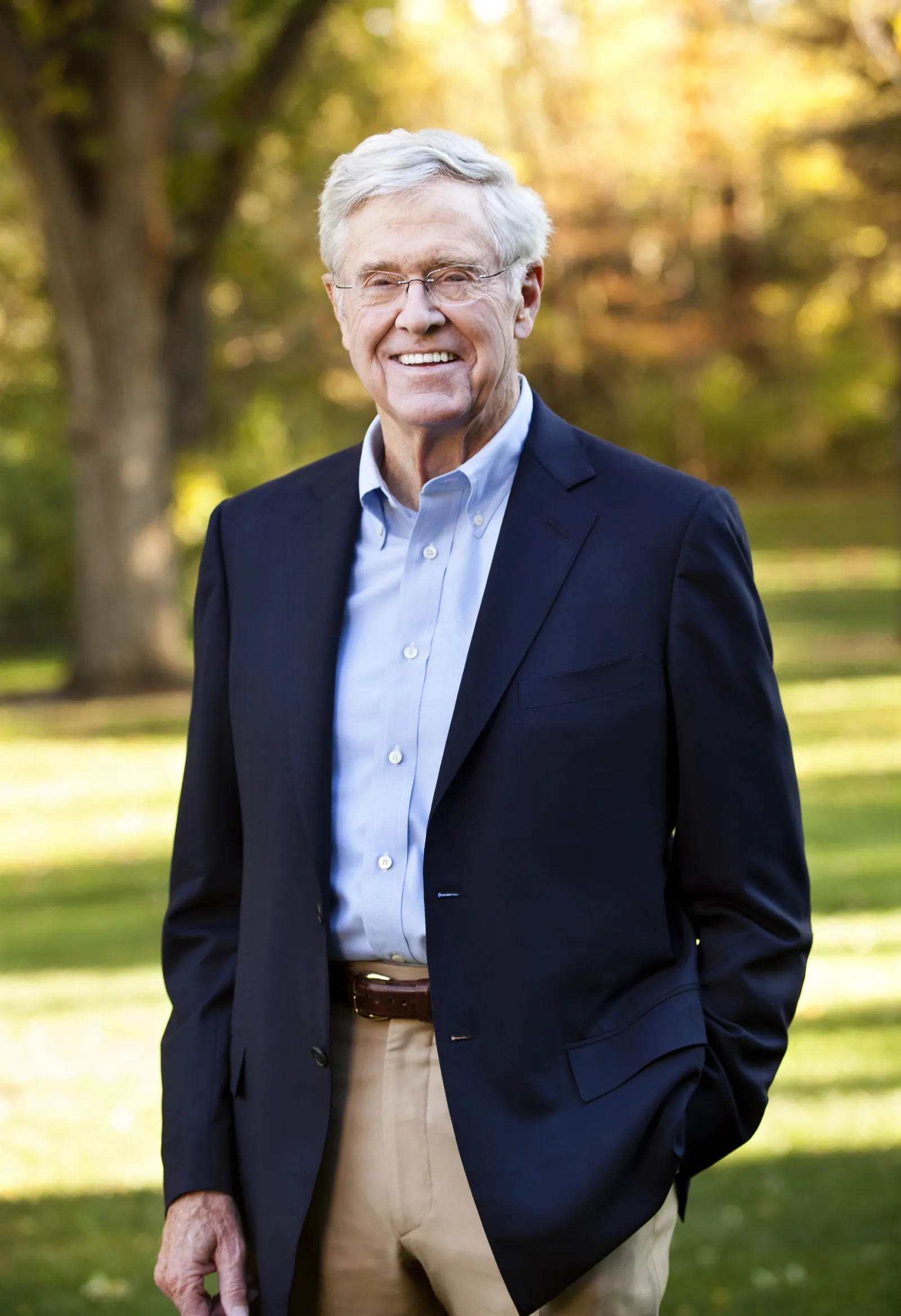

The Koch brothers

Charles (born 1935) and David (1940–2019) Koch, usually referred to as the “Koch brothers”, are the heirs of their parents’ company, Koch Industries, the second largest privately held company in the United States. Charles is the chairman of the board and has been the co-CEO since 1967, while David was the executive vice-president.

Drawing their immense wealth from this petroleum empire – their father invented a new process for transforming crude oil into gasoline – the Koch brothers have devoted their time and personal capital to promoting libertarian ideas in politics. Over the years, their strategy has shifted from supporting existing libertarian institutions towards deploying their own political network to innerve conservative politics with libertarianism.

Their political involvement started with their economic support and personal participation to the Libertarian Party – David ran for Vice-President for the party’s candidate in the 1980 presidential elections. In the 1980s, they also started funding libertarian think tanks such as the Cato Institute and the Mercatus Center, and began sponsoring university programs and grants through the Charles G. Koch Foundation, for university scholars to research free-market ideas and policy, and to encourage research aimed at documenting the negative impact of any social, collectivist or redistributive measure on the market economy. In 1984, they founded their own organization, Citizens for a Sound Economy, to directly lobby for tax cuts and deregulation on behalf of corporate clients.

During Bush senior and Obama’s presidencies, they massively supported the 60 Plus Association to campaign against their social security and health programs policies. Starting in 2003, the brothers also fostered networking among wealthy donors by holding bi-annual seminars with conferences about free-market theory and political strategies to implement libertarianism, as well as “one-on-one” sessions with Koch organization leaders and donors. By inviting Republican Party candidates and members to these seminars, the Koch brothers began their operation of libertarian influence on the Great Old Party, which they pursued with the creation of the network Americans for Prosperity (AFP) in 2004.

The organization is present in 36 states, and combines advertising, lobbying and grassroots agitation during and between election cycles – their website claims they have more than 4 million members in all 50 states. In the last 20 years, AFP has grown in importance and has pulled the Republican agenda to the right mostly because, as scholars Skocpol and Hertel-Fernandez have shown, a large part of AFP state directors and employees have previously held positions in the Republican party staffs or in election campaigns, or leave AFP to return to the party ranks, where they will pursue the libertarian AFP agenda1. These revolving doors allow AFP to know how to leverage the party, like obtaining legislative victories, for example.

While the Koch brothers have relentlessly sought to influence U.S. elections for nearly 50 years, their impact on the political process began to take on both a sprawling and decisive scale in the 2010s, through their massive funding of the Tea Party in an effort to undo the ‘socialist’ Barack Obama. Early champions of libertarianism, staunch climate change deniers, and outspoken opponents of democracy, Charles and David Koch have over the years invested hundreds of millions of dollars in the radical rightward shift of the American political landscape—until they achieved the return on investment we now see today.

1 Skocpol T, Hertel-Fernandez A. The Koch Network and Republican Party Extremism. Perspectives on Politics. 2016 ;14(3):681-699. doi:10.1017/S1537592716001122

David Sacks

Named “White House AI and Crypto Czar” by Donald Trump in December 2024, David Sacks is a Silicon Valley entrepreneur and investor with no prior government experience. An early member of the PayPal mafia – he was Chief Operating Officer when eBay purchased PayPal in 2002 – he has remained an associate of Elon Musk and Peter Thiel who, like him, were born in Apartheid South Africa.

A long-time paleolibertarian – he co-authored The Diversity Myth: Multiculturalism and the Politics of Intolerance with Peter Thiel back in 1995 – Sacks has recently played a notable role in Silicon Valley’s rightward drift thanks to his influential business and technology podcast All-In –- 766k subscribers on YouTube - which he co-hosts with three other venture capitalists, Jason Calacanis, Chamath Palihapitiya and David Friedberg.

After his friendship with J.D. Vance brought him close to Donald Trump, Sacks hosted a fund raiser for the Republican candidate in June 2024, raising $12 million for the campaign. His duties as AI and Crypto Czar have not been made clear by the POTUS, but the general idea is to lift all forms of burdensome regulations, in order to “MAKE AMERICA GREAT in these two critical technologies”. Sacks serves as a “special government employee,” a status that allows him to work for the government without undergoing confirmation hearings and disclosing his financial statements. Consequently, he will remain a general partner at Craft Ventures, a venture capital fund he co-founded.

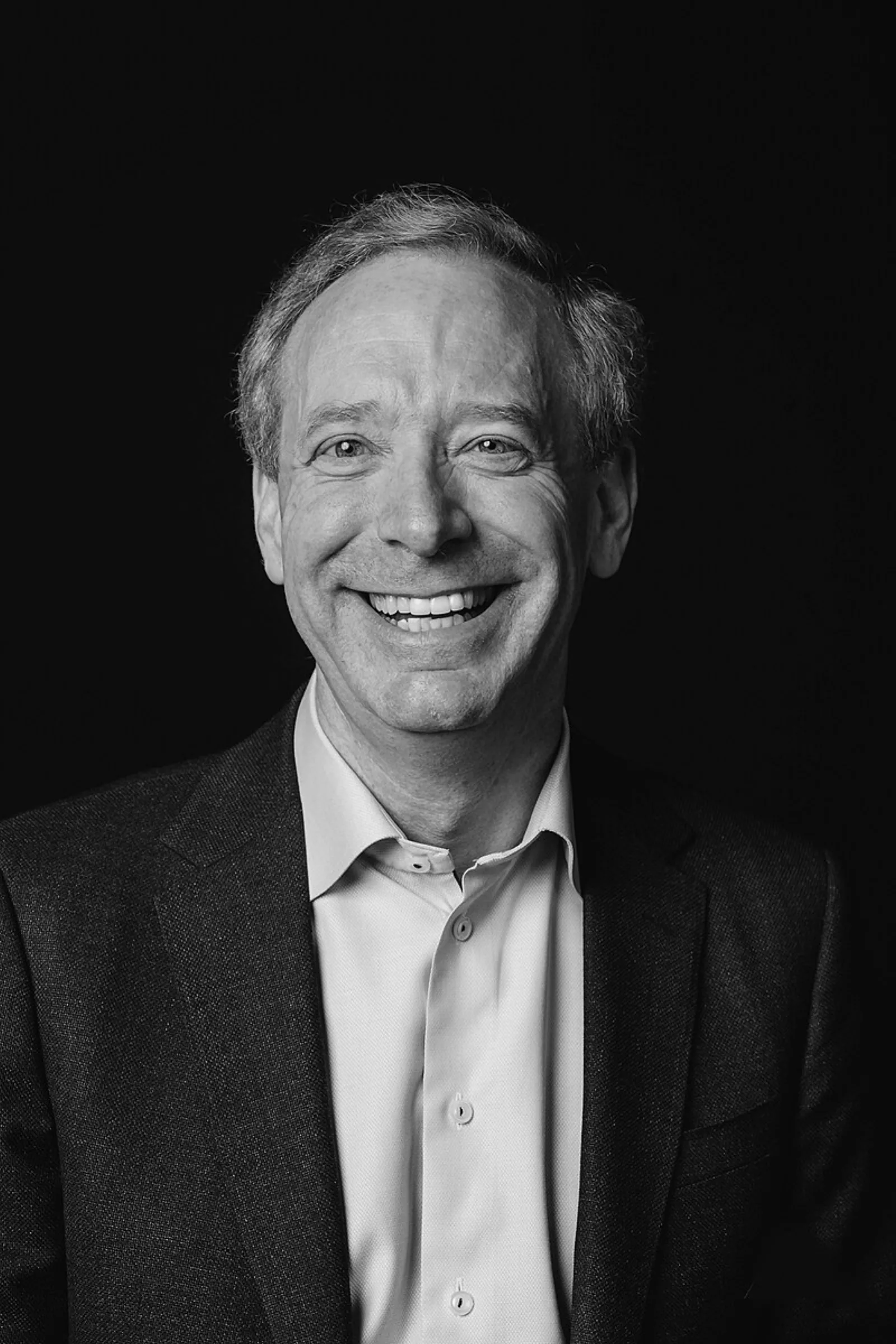

Michael Jensen

In their article about the influence of agency theory on the practices of boards, analysts and fund managers, the sociologists Jiwook Jung and Frank Dobbin write that “economic theories function as prescriptions for behavior as much as they function as descriptions. Economists and management theorists’” they add, “often act as prophets rather than scientists, describing the world not as it is, but as it could be.”1 Michael Jensen certainly illustrates that statement: more than for describing the workings of a corporation or even for anticipating a change in corporate governance, he can be credited for having contributed to the fulfillment of his own prophecies.

Born in Minnesota in 1939, “Mike” Jensen, who died in 2024, was trained at the University of Chicago School of Business, where he received an MBA in 1964 and a PHD in 1968. Two years later, Milton Friedman published his famous New York Times Magazine op-ed entitled “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits.” Railing against corporate social responsibility, which he saw as a sure path toward “pure and unadulterated socialism”, Friedman rejected the notion that corporate managers were accountable to all the stakeholders of the firm that employed them. The only purpose of their jobs, the economist asserted, was to make as much profit as legally possible, not for the company itself but for the people employing them, namely the shareholders of the corporation.

Jensen converted Friedman’s provocation into a doctrine of corporate management in 1976, when he and William Meckling wrote “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure.” The starting point of this hugely influential article was a problem that Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means had identified back in 1932: the separation of ownership and control in modern US corporations. Because publicly traded companies typically had myriads of shareholders, Berle and Means had explained, corporate power was in the hands of salaried managers. These CEOs confidently invoked their loyalty to the firm – as opposed to the special interests pursued by capital owners, employees and consumers – in order to legitimize their rule.

Whereas Berle and Means saw the “modern corporation” as a fait accompli, and thus called upon the government to check and regulate managerial power, Jensen and Meckling, following Friedman’s lead, thought that ownership and control could be once again reconciled. All it would take, they believed, was to challenge the notion that the corporation was an artificial person whose interests were distinct from those of the people holding its stock. In Jensen’s own words, “this was the beginning of breaking open the black box of the firm.” According to Jensen and Meckling’s “agency theory”, a corporation was no more than a bundle of contractual relations between a “principal” – i.e., the owners of the capital – and a wide variety of “agents”. The latter were thus contractually bound to do the bidding of the former.

“Theory of the Firm” purported to delegitimize managerial authority in the name of shareholder democracy: its authors eagerly presented themselves as the vindicators of disempowered stock owners fighting the good fight against unaccountable technocrats. Their true purpose, however, was to ward off the prospect of a stakeholder democracy, whereby the corporation would be accountable to all the people affected by its operations. Heeding Friedman’s warning, Jensen and Meckling reckoned that when “a business takes seriously its responsibilities for providing employment, eliminating discrimination (and) avoiding pollution,” socialism is just around the corner.

While “Theory of the Firm” made a powerful case against “corporate social responsibility” – at least for the readership of the Journal of Financial Economics – a practical question remained: how could managers be either compelled or convinced to serve the interests of their “principal”? Jensen’s answer involved a mix of carrots and sticks:

On the one hand, in an article called “CEO Incentives: It Is not How Much You Pay but How”, he and Kevin Murphy argued that once CEOs were compensated in stock options and other performance-based incentives, they would inevitably see eye to eye with capital owners.

On the other hand, to further dissuade corporate managers from neglecting the pursuit of shareholder value, Jensen advocated threatening them with leveraged buyouts (LBOs): the fear of having financial raiders take over the firm with borrowed money, he wrote in "Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance, and Takeovers,” would go a long way toward disciplining recalcitrant agents.

After teaching at the University of Rochester from 1967 to 1986, and founding the Journal of Financial Economics in 1974, Jensen joined the Harvard Business School as a full professor in 1988. The course he taught on “Coordination, Control and the Management of Organizations,” proved immensely popular both with the students who wanted to be hired by Wall Street Firms and with the partners of these firms, who showed their gratitude by amply funding the Harvard Business School. Jensen was then recognized as the indefatigable champion of shareholder value, leveraged buyouts, stock options and golden parachutes.

By the mid-2000s, however, as Wall Street got increasingly mired in scandals and fraudulent bankruptcies – from Enron to Lehmann Brothers – Jensen had a change of heart, of sorts. While still wedded to his conception of the firm, he complained that the business world was riddled with moral flaws: “stock options”, he lamented in a New Yorker interview, have become “managerial heroin.” After retiring from Harvard, Jensen met Werner Erhard, the self-improvement guru and founder of EST. Together, they launched a so-called Erhard/Jensen ontological/Phenomenological Initiative in 2012, the purpose of which was to give weeklong seminars about “integrity”, mostly at beach resorts.

Pete Hegseth

Pete Hegseth has been appointed Secretary of Defense by Donald Trump for good reasons: during his long tenure as a co-host on Fox and Friends, one of Trump’s favorite TV shows, he not only played a key role in persuading the then 45th President to pardon three US soldiers indicted for war crimes in Afghanistan and Iraq (in 2019) but also emulated his current boss by purchasing the silence of a woman who had accused him of rape (in 2017). More broadly, Hegseth matches the new administration’s view of a Secretary of Defense in pretty much all respects.

First, after serving in the military three times (2003-2006, 2010-2014, 2019-2021), including as a national guardsman at the Guantanamo Bay prison and as a volunteer in Iraq and in Afghanistan, he resigned from what he would later call a woke army when he was barred from attending Joe Biden’s inauguration on account of his Deus vulttattoo – a reference to the Crusades that is a notorious sign of allegiance to the Christian nationalist far right.

Second, a Christian nationalist is precisely how Hegseth defines himself: as such, he blames the declining “glory” of the US army on DEI (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion) policies and is staking its restoration on the firing of transgender soldiers, the exclusion of women from combat positions, and the drastic reduction of the number of non-white and non-Christian officers. Lately, if only to make his intentions clearer, he decided to introduce a “Secretary of Defense Christian Prayer & Worship Service” in the Pentagon’s auditorium - a monthly event meant to praise God but also Donald Trump as a divinely appointed leader.

Third, Pete Hegseth’s approach to management is also inspired by or least congruent with that of the man he serves. Indeed, back in the mid-2010 – before becoming a full-time Fox News host – the Secretary of Defense was forced to resign from “the two nonprofit advocacy groups that he ran—Veterans for Freedom and Concerned Veterans for America—in the face of serious allegations of financial mismanagement, sexual impropriety, and personal misconduct1.”

Finally, since his appointment at the head of the Department of Defense, Hegseth has displayed a sense of boundaries – between the private and the professional – that is also resonant with Trumpworld practices. In particular, he has failed to resist the urge to share sensitive information about an impending bombing operation in Yemen with a journalist of The Atlantic– over a chat on Signal – and to invite his wife to several confidential meetings. More than his irresponsible behavior, however, what is most remarkable in this episode is Hegesth’s eagerness to brag about the imminent killing of Yemeni civilians.

1. Jane Mayer, “Pete Hegseth’s secret history”, The New Yorker, December 1, 2024.

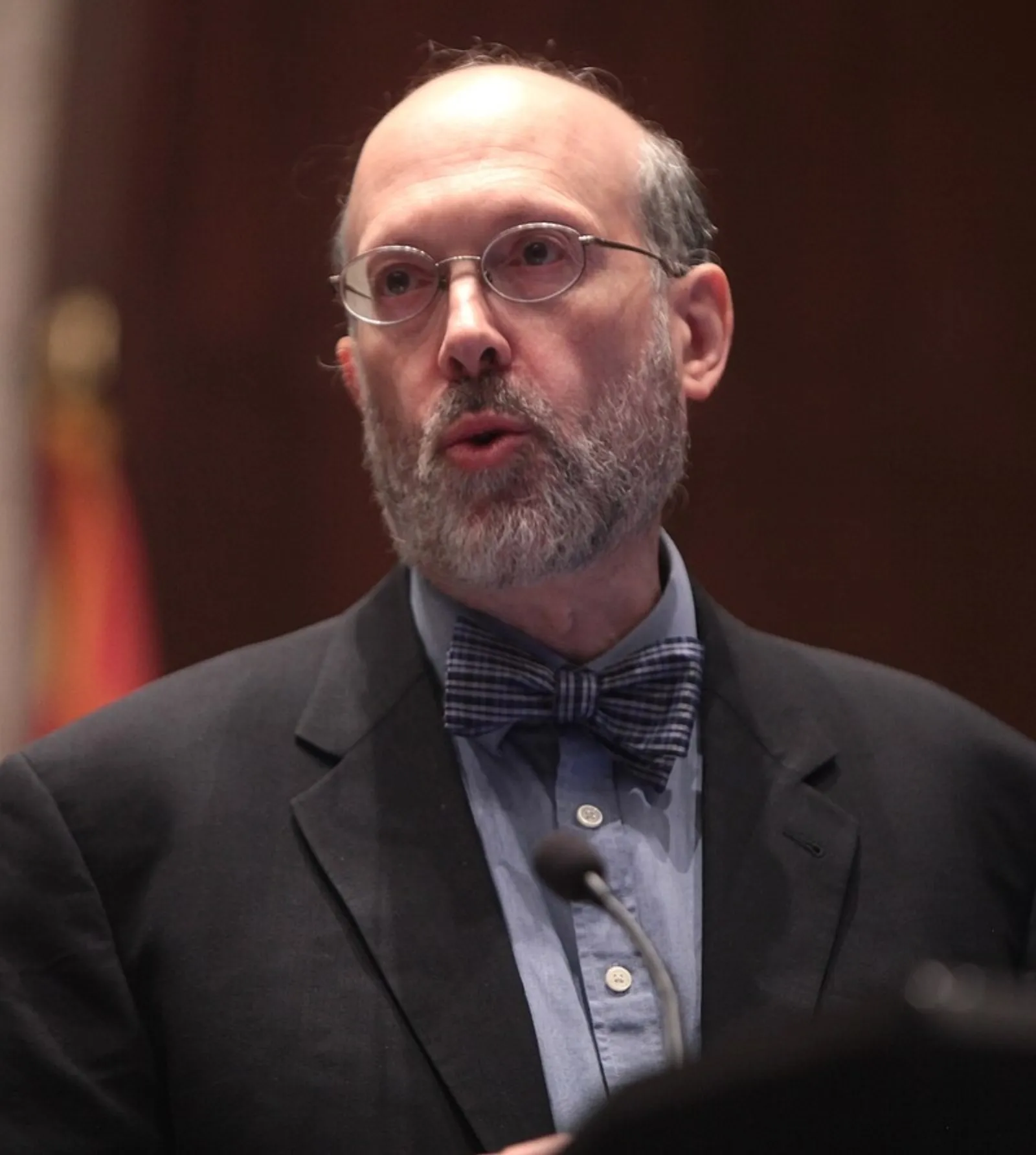

Philip Hamburger

A professor of constitutional law and of legal history at Columbia University, Philip Hamburger is one of the chief crusaders against the “tyranny” of the American administrative State. In 2014, he established the Columbia Law School’s Center for Law and Liberty, which focuses on what paleolibertarians like himself identify as the major threats to freedom – from Universities’ Institutional Review Boards establishing criteria for sound research to Big Tech’s allegedly censorious monitoring of content and liberal biases against religious discourse.

Three years later, as Donald Trump was taking office, Hamburger founded and became the CEO of the New Civil Liberties Alliance (NCLA), a nonprofit and ostensibly nonpartisan organization largely funded by Charles Koch and Leonard Leo. As the names of its sponsors convey, the NCLA is designed to “protect constitutional freedoms from violations by the administrative state.” Its lawyers typically bring cases against the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which they accuse of usurping the power of the government’s executive branch. In his activist endeavors as well as in his books and articles, Hamburger has been an intellectual architect of the Trump coalition’s approach to freedom fighting.

One of the main causes he champions – first in his 2002 book Separation of Church and State, then in its 2018 sequel Liberal Suppression – involves what he considers to be an abusive interpretation of the First Amendment. According to him, invoking the constitutional protection of free speech as a justification for the separation of Church and State is a wrongheaded reading of the American Constitution predicated on a longstanding anticatholic tradition. Instead of protecting religious freedom from governmental overreach, Hamburger complains, judges have increasingly enabled the State to police the expression of religious speech and confine it to the private sphere. In Liberal Suppression – subtitled: Section 501(c)(3) and the Taxation of Speech – the originalist legal scholar further argues that threatening to deprive charities of their non-profit fiscal status if they refuse to renounce practices that post-civil rights norms deem discriminatory represents an infringement on religious freedom typical of a police State – especially considering that the framers of the Constitution wanted religious freedom to be unconditionally protected.

Yet what arguably constitutes Hamburger’s main contribution to the advancement of the far-right agenda is the maximalist case he makes for the Unitary Executive Theory (UET). The latter, which is now embraced by a majority of Justices in the Roberts Supreme Court, states that the President possesses sole authority over the executive branch. Supporters of the theory, like the late Justice Antonin Scalia, claim that, as the “only person who alone composes a branch of government”, the President has been vested with “not some of the executive power, but all of the executive power”1. The main implication of the UET is that presidents can remove at will any subordinate officials of the Executive branch, whether appointed by their predecessors or by themselves.

In a 2014 book called Is Administrative Law Unlawful? Hamburger takes on the unanimous 1935 opinion in Humphrey’s Executor v. United States, which endows administrative agencies with “quasi-legislative” and “quasi-judicial” powers inside the purview of the missions assigned to them by Congress – be it the protection of the environment or the enforcement of civil rights. According to the Columbia law professor, congressional delegation of rulemaking and adjudicational responsibilities is the very process through which a “deep state” takes control of the citizenry – under the guise of protecting its liberties and securing its welfare. To fight the entrenchment of administrative despotism, therefore – which he compares to early modern monarchical power – Hamburger paradoxically advocates for the subordination of these agencies to the sole authority of the White House. Public administration employees, in other words, should be perceived as agents hired and paid to execute the decisions of the President.

Hamburger’s perspective on the UET has been recently vindicated by two Court decisions, Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo and the Relentless, Inc. v. Department of Commerce, which have canceled the so-called Chevron deference, a doctrine that compelled courts to defer to the interpretation of federal statutes by administrative agencies. Altogether, his work is paradigmatic of the libertarian weaponization of freedom, whether to foster the interests of religious organizations, curtail the public oversight of private companies or legitimize the advent of an authoritarian presidency.

1 See Antonin Scalia’s dissenting opinion in Morrison, Independent Counsel vs. Olson et al., 1987: https://tile.loc.gov/storage-s...

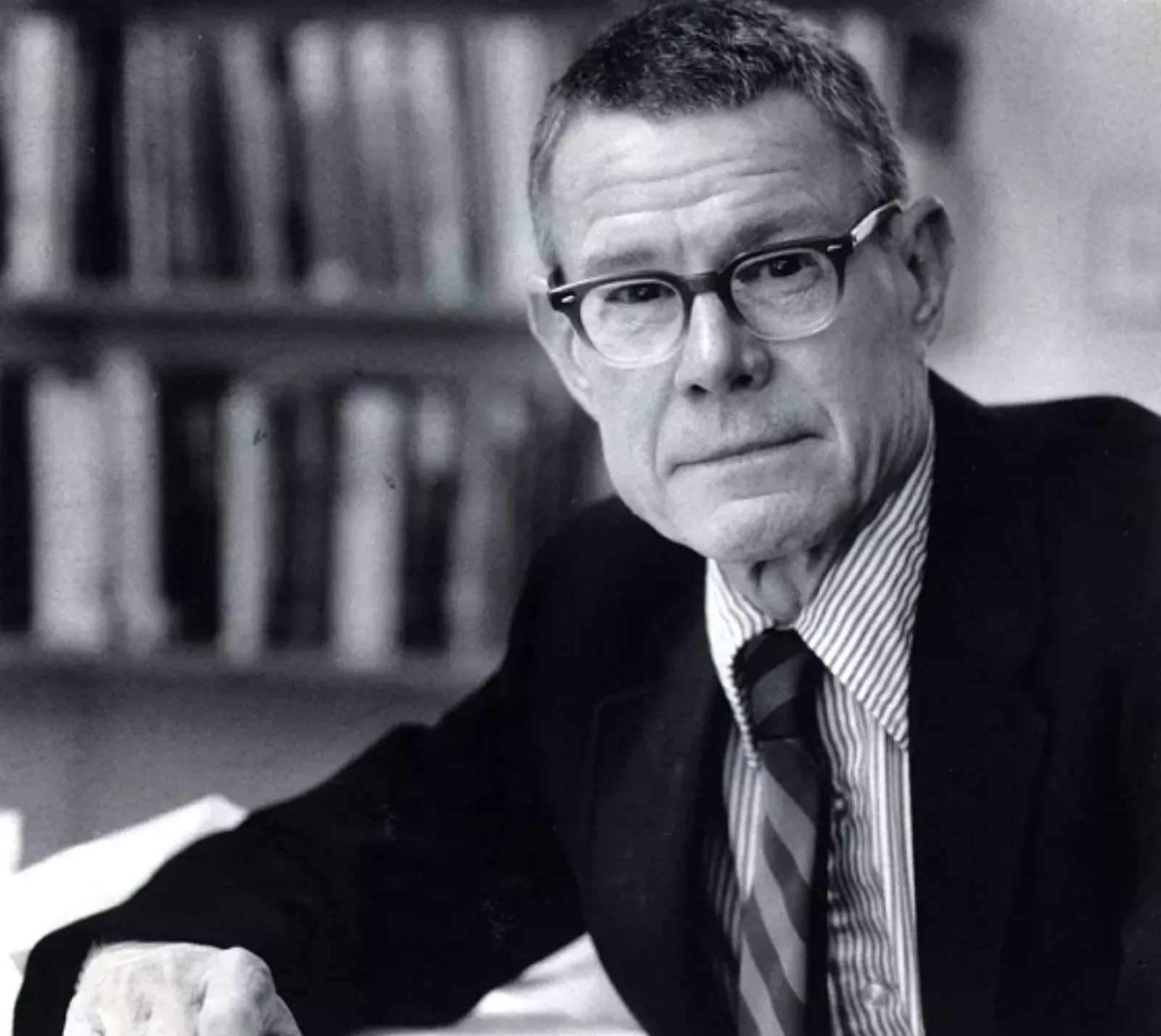

James M. Buchanan

Born in 1919, James McGill Buchanan was raised in rural Tennessee. His grandfather had been a governor of the state, elected on the Farmers’ Alliance platform, but by the time James came along, the family had lost both its political clout and its economic resources. Encouraged to redeem the Buchanan name and reputation, the future leading figure of the Virginia School of Economics did so by way of a successful academic career, which started when he was accepted at the University of Chicago for a PHD in economics.

Still informed by his grandfather’s populism when he entered the program, Buchanan quickly converted from what he called socialism to the pro-free market mindset of his teachers – Frank Knight but also the younger faculties, Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek. The latter quickly recognized the newcomer’s potential and made him a member of the Mont Pelerin Society. After completing his PHD, Buchanan taught in Tennessee and in Florida before joining the University of Virginia in 1957, where he cofounded the Jefferson Center for Studies in Political Economy and Social Philosophy.

The Center was bankrolled by the very conservative Volker Fund and soon became one of the main laboratories of neoliberal thought in the US. As eager as his comrades to discipline democracy and curtail the ability of elected officials to tax and spend, Buchanan decided to do his part by extending the Chicago School’s perspective on human conduct to the field of politics. His theory of Public Choice – for which he received the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1986 – sought to legitimize the neoliberal agenda by showing that politicians and civil servants behaved like everybody else. Notwithstanding their pretense to work for the public good, they were nothing but rational, self-interested and forward-looking utility maximizers.

What distinguished democratically elected leaders and public sector employees from ordinary people, Buchanan argued, was both the widespread misconception about their motives and the unchecked power they wielded – whether justified by the popular mandate they claimed or predicated on their civil servant status. To undermine what he saw as the rent-seeking propensities of government officials, Buchanan advocated two kinds of political measures. The first kind was designed to curb the authority vested in popular sovereignty. It consisted of imposing constitutional restrictions on a government’s right to run a deficit and of multiplying the cases where a congressional super-majority would be required in order to pass a bill. The second kind of reforms aimed to change the behavior of public employees. The way to proceed was to make their jobs as incumbent on performance and as subjected to competition as those of their private sector counterparts.

Outlined in The Calculus of Consent – a book co-authored with Gordon Tullock and published in 1962 – Public Choice Theory proved successful enough to endow Buchanan with ample academic recognition and funding. By the mid-60s, however, the administration of the University of Virginia began to worry about the rigid political orientation of the Jefferson Center. Buchanan reacted by disbanding the Center and leaving the University altogether. In 1968, he joined the economics department of UCLA, but only to be both deeply traumatized and further radicalized by the student activism he encountered on campus.

Hitherto convinced that, in the US at least, a vast majority of voting citizens were sufficiently attached to property rights, family values and genuine federalism to limit the growth of the welfare state, Buchanan suddenly grew more pessimistic but also more resolute. On the one hand, the year he spent at UCLA persuaded him that the preservation of the liberal political order called for the imposition of stricter constitutional limitations on majority rule. Otherwise, he argued in The Limits of Liberty, the electoral system would inevitably favor the enfranchised beneficiaries of welfare provisions, affirmative action programs and labor union privileges at the expense of hard-working homeowners and entrepreneurs. But on the other hand, Buchanan also came to the realization that the required reforms could only be implemented if a powerful social movement demanded them. Hence his pivotal involvement, as an organic intellectual, in the Californian tax revolt of the late 1970s.

After leaving UCLA in 1969, Buchanan came back to Virginia and, with Tullock, established a Center for Study of Public Choice at the Virginia Polytechnic Institute. He was hardly done with California, however. In 1972, he joined the Tax Reduction Task Force convened by Ronald Reagan, who was then the governor of the state. If “someone of the national scale of Governor Reagan could take the lead”, Buchanan wrote upon joining the Task Force, one could finally hope “to get a taxpayer revolution off the ground.”

The rationale behind this revolutionary prospect was that the never-ending expansion of progressive taxes and deficit-financed programs was eventually bound to cause more resentment than relief. Rather than enjoying the social benefits and public services provided by the state, an increasing portion of the voting population would feel that the tax-dollars collected from the product of their labor were being spent on rent-seekers – whether idle welfare recipients, lazy and overprotected functionaries, privileged union members, or out-of-touch yet patronizing public school teachers and intellectuals. Once properly mobilized against the federal state’s bias towards these allegedly parasitical groups, Buchanan believed that taxpayers could be turned into the kind of revolutionaries that had brought his grandfather to power, but also that they would demand neoliberal reforms purposed to protect the makers from the takers.

Buchanan’s vision was vindicated by the success of the referendums on proposition 13 in 1976 and proposition 4 one year later, which not only drastically restricted property taxes and local government appropriations but also required a two third super-majority in both state house and senate to make any change in California’s fiscal policy. Then, in 1980, the possibility of extending the Californian trend to the national level became very real with the landslide election of Ronald Reagan to the presidency. Having relocated his Center for Study of Public Choice at George Mason University in 1983, Buchanan could now count on the generous support of the Koch brothers. At the helm of what the Wall Street Journal called “the Pentagon of conservative academia”, he remained, until his death in 2014, an indefatigable promoter of neoliberal constitutional reforms – from the balanced budget amendment to the abolition of social security, which he compared to a Ponzi scheme. Though both initiatives kept failing at the federal level, Buchanan’s relentless assaults on government’s profligacy continue to inform the legislation of a vast majority of states: to this day, 44 of them require their legislature to pass a balanced budget.

Palmiro Togliatti

Palmiro Togliatti occupies a singular place in the history of the Italian left. As the founder of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) and an outspoken opponent of fascism, he was also a man of compromise who gave up on his revolutionary hopes after the resistance war.

A friend of Gramsci, he joined the Italian Communist Party (PCI) in 1914 and campaigned on its far left for its transformation into a revolutionary party. Faced with the PSI’s reformism during the factory occupations of the biennio rosso, he broke away and participated in the founding of the PCI at the Livorno Congress. In the 1920s, Togliatti took on increasing responsibilities within the party and distinguished himself as a privileged intermediary between Moscow and Europe. After Gramsci’s arrest, who had become secretary general of the PCI, Togliatti also faced repression. Fortunately, he was in Moscow when the main Communist leaders were arrested. Appointed to the party leadership, he worked from abroad to organize the PCI clandestinely and develop a strategy to defeat fascism, which gradually took the form of the “popular front policy”. His analysis of fascism as a “reactionary mass regime” is recorded in the “Course on Adversaries” he gave in Moscow in the spring of 1935.

During the war, the anti-fascist struggle was closely tied to the fight against capitalism (see text on the Action Party in chapter 2). It was in this sense that the various resistance parties (the PCI, PSI, and Partito d'Azione) agreed on a principle of non-compromise with the monarchy. The anti-fascists demanded the king’s abdication and Marshal Badoglio’s resignation, both of whom were accomplices of Mussolini’s regime, in order to prevent the popular resistance effort from being hijacked by the monarchist elite.

Yet, when he returned to Italy in March 1944, Togliatti broke with the anti-fascist line and called for the formation of a government with the king and Badoglio. This break, known as the “Svolta di Salerno”, can be explained by directives he received from Stalin on the night of March 3-4, 1944. These directives prioritized the geopolitical interests of the USSR, (i.e., the consolidation of Italy’s power vis-à-vis Germany and England), rather than the interests of the Italian working class. Where anti-fascism could have led to the construction of a new political order, the Salerno turning point neutralized its aspirations and replaced it with diplomatic anti-fascism, under the leadership of the Communist Party.

After Italy’s Liberation, Togliatti found himself at the head of the largest communist party in the West, and seemed determined to do everything in his power to integrate it into liberal democracy. The amnesty he signed on June 22, 1946, as Minister of Justice, was intended to promote Italian reconciliation after the civil war and stabilize the Republic’s institutions. In concrete terms, it absolved thousands of fascists of their war crimes and allowed them to remain in their positions in the administration, the army, and large companies. Although aggravated crimes were theoretically excluded from the amnesty, these exceptions were rarely applied by the Italian judiciary, 90% of whom were still from the fascist administration. On the other hand, partisans were prosecuted by the courts, which fueled deep resentment among former resistance fighters. While this gesture helps us understand how Italy’s transition from fascism to democracy took place, it also explains the survival of fascism in democracy. Indeed, the amnesty allowed for the rapid rebirth of legal political fascism, with the founding of the Italian Social Movement in 1946. By prioritizing institutional and state reconstruction, Togliatti and the PCI participated in a process of erasing the memory of fascist crimes, which has long benefited the Italian far right.

The trajectory traced by Togliatti, who remained at the forefront of the PCi until his death in 1964, demonstrates the ways in which anti-fascism was overtaken by heterogenous logics (Soviet, conservative, and liberal), and thus diverted from its initial goal.

Beppe Grillo

An accountant by training who later became a comedian and then a populist leader, Beppe Grillo is a key figure for understanding the transformations of Italy’s political landscape in the 2010s. He gained nationwide fame through his satirical stage shows and television appearances, where he filled stadiums and drew laughter by relentlessly castigating Italian politicians, whom he accused of widespread corruption. Critical of the operations of major industries, Grillo often relied on experts to grasp the technical dimensions of the issues he addressed, incorporating this detailed knowledge into his performances. When Telecom Italia was privatized, for instance, he purchased shares in the company in order to secure an invitation to its annual general meeting, where he publicly denounced the privatization in front of its investors.

Beppe Grillo’s career took a decisive turn in the early 2000s, following his meeting with Gianroberto Casaleggio. After encountering Casaleggio, a specialist in digital communications, at the end of one of his shows, Grillo was encouraged to create a website through which he could disseminate his views on current affairs and politics. Launched in 2004, Beppe Grillo’s blog quickly became a must-read platform in Italy. He used it to denounce politicians’ spending practices and the lack of generational renewal within the political class, which he described as a “gerontocracy.” The blog also served as a space to criticize the privatization of public services and the corruption that accompanied these processes. In 2007, drawing on his growing influence, Grillo called for the organization of a “Vaffanculo Day”, held on September 8. Thousands of people gathered across the Italian peninsula to collect signatures in support of a proposed bill titled Clean Parliament, an explicit reference to the Mani pulite investigations. The bill sought to bar individuals with criminal convictions from entering Parliament and to limit parliamentary careers to two consecutive terms. Although only 50,000 signatures were required, the Grillini collected more than 300,000.

In October 2009, Grillo founded the Movimento Cinque Stelle (Five Star Movement). Claiming to be “neither right nor left,” the party adopted a populist orientation, both in its methods and in the substance of its demands. Its five core themes echoed the topics developed on Grillo’s blog and were designed to appeal to a broad constituency by addressing issues that directly affected people’s material conditions while articulating a shared critique of governmental mismanagement: the return to public control of water services, a zero-waste policy, the expansion of sustainable public transport, a transition to renewable energy, and free access to Wi-Fi. Corruption remained a pervasive concern throughout the movement’s discourse, while free Internet access was framed as a means of circumventing the political propaganda disseminated through television.

Grillo and Casaleggio devised an organizational structure that they believed would guard against the corruption they denounced in other political parties. Their so-called “transparency strategy” stipulated that both party policies and electoral candidates would be selected through online voting. The movement was almost entirely digitized: it had no physical headquarters, and the Internet—still only partially embraced by its political rivals—served as the primary infrastructure for what they presented as a form of direct democracy. All of the movement’s statutes, press releases, and policy proposals were made publicly available online. Communication took place almost exclusively through social media. Viewing the press as hostile, the movement avoided making major announcements through newspapers and sharply limited its presence on television. The party also claimed to operate without a hierarchical structure. Candidates were expected to embody the moral integrity that the movement accused other politicians of lacking: elected representatives were required to have clean criminal records and to commit themselves to opposing public funding for political parties. Because Beppe Grillo had been convicted in 1980 of involuntary manslaughter following a car accident that resulted in three deaths, he was therefore ineligible to stand for election. Rather than weakening his authority within the movement, this restriction paradoxically reinforced his popularity, as it was interpreted by supporters as a guarantee of his sincerity. At the same time, Grillo retained the power to exclude activists who challenged him.

Despite this emphasis on direct democracy, criticism of the established order, and interest in environmental issues and certain public services, Beppe Grillo did not defend workers’ rights. A precursor to Javier Milei and Donald Trump, he mobilized his critique of the political system to attack specific aspects of the state, particularly social welfare. Echoing the anti-state rhetoric of Berlusconi’s right wing, he denounced “welfare dependency” and criticized the power of trade unions. The model of society he promoted was environmentally oriented but rested above all on individual responsibility. Through this combination, Beppe Grillo and the Five Star Movement succeeded in attracting voters from both the right and the left. The movement quickly achieved electoral success. In the February 2013 legislative elections, Grillo’s party upended the political landscape by winning 25.6% of the vote in the Chamber of Deputies and 23.8% in the Senate. It thus sent 109 deputies to the Chamber and 54 senators to the upper house. All were politically inexperienced, and their arrival initially disrupted established parliamentary routines. Enrico Letta, Prime Minister from 2013 to 2014, acknowledged that “it woke us up. And it is largely thanks to them that we chose new figures to lead the assemblies: a former anti-Mafia magistrate in the Senate [Pietro Grasso] and a former official of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in the Chamber [Laura Boldrini]” (1). In 2014, seventeen Grillini were elected to the European Parliament, even though the movement had long embraced the anti-EU stance of its founder, who viewed Italy’s representation in the European Union as excessively costly. In the June 2016 municipal elections, the Five Star Movement won mayoral races in Rome and Turin. Beppe Grillo’s party benefited significantly from the crisis of the Italian right, particularly the conflict that had been ongoing since 2010 between Silvio Berlusconi and his former ally Gianfranco Fini. In 2014, the exposure of a scandal involving rigged public contracts for the organization of the 2015 Milan World Expo—implicating both Berlusconi and the Democratic Party—further boosted the Five Star Movement’s popularity. In the 2018 legislative elections, it emerged as Italy’s leading party with 32% of the vote and formed a coalition government with Matteo Salvini’s League, led by Giuseppe Conte, who was close to the movement.

However, the arrival of the Five Star Movement in government marked the beginning of its decline. Indeed, inconsistencies soon became apparent: once in power, the movement did not overthrow the traditional elites. Its anti-establishment promises seemed hollow. The universal basic income promised by Beppe Grillo was implemented, but on a much smaller scale than had been claimed. As the movement’s election results declined and Conte’s government collapsed due to conflicts within the coalition, Beppe Grillo was disavowed by his base. In November 2024, his role as “guarantor” of the party was removed by a vote of the movement’s constituent assembly. Nevertheless, he continues to preach to the converted by updating his blog.

Sources

(1) "L’irrésistible ascension d’un ovni politique", Jérôme Gautheret, Le Monde, 13 mars 2017

"En Italie, la normalisation politique du Mouvement 5 étoiles", Jérôme Gautheret, Le Monde, 17 novembre 2020

"Le temps des frondeurs", Raffaele Laudani, Manière de voir, 1e avril 2021

"L’homme de la semaine : élections législatives en Italie", Philippe Ridet, Le Monde, 7 janvier 2013

"Beppe Grillo navigue sur l’impuissance de la politique", Gaël de Santis, L’Humanité, 21 mai 2014

Gianfranco Fini

Born in 1952, Gianfranco Fini kept Mussolini’s fascist legacy alive until the end of the 20th century. A journalist by training, he cut his teeth in the Youth Front, the youth wing of the Italian Social Movement (MSI), a neo-fascist party founded in 1946 by ex-leaders of the Republic of Salò, among others, and attended by former members and nostalgics of the fascist regime. The Youth Front enjoyed a certain degree of autonomy from the MSI and did not function solely as an institutional organization. Like many far-right movements, especially those made up of young people, the Youth Front used violence as a means of political action. During the Years of Lead, Youth Front militants and anti-fascist activists regularly clashed in violent and sometimes deadly encounters.

A protégé of MSI leader Giorgio Almirante, Fini rose rapidly through the Youth Front’s ranks, being appointed president by Almirante in 1977, a position he held until 1988. He was then elected secretary general of the MSI. Since 1947, the Italian Social Movement had been excluded from the “Constitutional Arc”: to keep fascism, which the MSI claimed to represent, at bay, all parties had agreed never to include it in an electoral alliance and never to allow any of its members to join the government. To come to power, the MSI had no choice but to try to expand its electorate by its own means. Convinced that, for the party to gain popularity, it needed to focus on winning over part of the Christian Democracy electorate (rather than trying to recruit communists, as some within the MSI suggested) Gianfranco Fini reoriented the party’s political line toward the center-right. This strategy proved successful a few years later, when the Christian Democrats were severely shaken by the Tangentopoli scandal, while no MSI members were targeted by corruption investigations. At the polls, the MSI gained in popularity. But the party’s allegiance to fascism and Fini’s sometimes colorful rhetoric prevented the MSI from becoming truly popular with the public. In 1989, Fini declared that he “still believed in fascism”; in 1990, he claimed that “Mussolini was the greatest statesman of the 20th century”; and, in 1994, that “Mussolini was not a criminal”. In 1993, he lost the Rome municipal elections in the second round. After this electoral defeat, Fini decided to adopt a new discursive strategy to give the MSI greater respectability. Neither fascist nor neo-fascist, he started posturing as a “post-fascist”.

Although the strategy to soften the party’s image was underway, it was not yet sufficient to completely alter public opinion. It was by collaborating with Silvio Berlusconi’s party, Forza Italia, that Fini managed to bring his party into government in 1994. At last, the “constitutional arc” was broken. Five ministers, including the vice-president of the Council of Ministers, were members of the MSI. To further reposition the party, particularly on the international stage, Fini decided in 1995 to transform the MSI into the “National Alliance”, while remaining at its head. The re-founded party removed all “archaic” fascist elements from the MSI’s political program, notably by swapping the corporatist vision of the state for market capitalism. Fini asserted that from then on, fascism would be nothing more than a historical reference and no longer the party’s ideology or objective. Under Fini’s leadership, the former MSI thus became a supposedly moderate right-wing party. A skilled tactician, he even made public appearances during which he denounced fascism, notably during a visit to Auschwitz in 1999—which did not prevent Polish anarchists from pelting him with eggs. During a diplomatic trip to Israel in 2003, he went so far as to say that Mussolini’s regime was “a shameful chapter in the history of our people” and that fascism was “absolute evil”. At the time, Fini was seeking Berlusconi’s position: with prosecutors closing in on Berlusconi, he hoped to replace him as head of the Council of Ministers if he were to resign. In the meantime, he held important positions in the Italian government and parliament. From 2001 to 2006, he was Deputy Prime Minister, a role he combined with that of Minister of Foreign Affairs from 2004 to 2006. From 2008 to 2013, he was President of the Chamber of Deputies.

In 2009, Fini and Berlusconi decided to merge the National Alliance and Forza Italia. But from 2010 onwards, Fini disapproved of Berlusconi’s policies, which he considered too closely aligned with those of the Northern League, and repeatedly called for the Prime Minister’s resignation before founding the parliamentary group Future and Freedom for Italy. However, he failed to win a seat in the 2013 elections, the first time since 1983, and withdrew from political life. In 2024, Fini was sentenced to two years and eight months in prison, a sentence he will surely not serve, after a media outlet owned by Berlusconi revealed that he had authorized the fraudulent sale of a Monegasque apartment belonging to the National Alliance to his partner’s family.

Enrico Berlinguer

Born in Sardinia on May 25, 1922, into a family of intellectuals, Enrico Berlinguer rose rapidly through the ranks of the Italian Communist Party, which he joined in 1944. In 1949, he became secretary general of the Communist Youth Federation, a position he held until 1956. He also served as president of the World Federation of Democratic Youth from 1950 to 1953. In 1956, the party’s secretary general, Palmiro Togliatti, invited him to join the PCI’s leadership group. When Luigi Longo died, he took his place at the head of the PCI in 1972.

Enrico Berlinguer is best remembered for the “historic compromise” he attempted to organize with the Christian Democrats in the 1970s. In an article published in the magazine Rinascita on September 28, 1973, entitled “Reflections on Italy after the events in Chile”, he drew the following conclusion from the assassination of Salvador Allende in Chile in 1973 and Pinochet’s coup d'état: in a world divided into two blocs, that of liberal democracy led by the United States and that of the Soviet Union, a union of the left could never come to power in Europe without being overthrown by a fascist coup organized by the CIA and networks of the Atlantic. He called on the Christian Democratic Party to “transcend partisan divisions” and form a coalition government to represent the majority of the Italian population.

Berlinguer was right to be concerned about US interference. On the one hand, there are plenty of examples of American interventionism after the war. On the other hand, Frédéric Heurtebize’s work traces the CIA’s surveillance of the PCI since the beginning of the republic, which intensified in the 1970s.

At the 14th PCI congress in Rome in March 1975, Berlinguer therefore made a formal proposal to establish an “historic compromise” with the Christian Democrats. For Aldo Moro, head of the DC, this was not without interest. While the PCI had won 27.2% of the vote in the May 1972 legislative elections, this figure rose to 34.4% in the June 1976 legislative elections. The DC would benefit greatly from the support of a party representing a third of the electorate and whose popularity was on the rise in order to remain in power. The DC had also just suffered a setback: although it had supported the repeal of the divorce law, almost 60% of the Italian population voted to retain it in the referendum of May 12, 1974, dealing a blow to the Christian Democrats’ symbolic stranglehold on political life.