Climate Denialisms

Climate change denial is as old as the scientific study of global warming. At the close of the Cold War, the same “merchants of doubt” who had previously sought to minimize risks associated with smoking, acid rain, and nuclear winter once again seized upon the epistemological problem of uncertainty—inherent in any form of scientific research—first to deny the warming effect of carbon dioxide, and then to obscure its impact.

Is climate denialism finally on the wane? Until recently, there seemed to be cause for guarded optimism. That an energy transition was necessary raised fewer objections, even if what passed as climate change awareness was essentially based on incentive pricing mechanisms (carbon taxes, emissions trading schemes) designed to internalize the ecological externalities of fossil capitalism. However, both the failure to keep global heating below the 1.5°C threshold set by the Paris Agreement and the rise of a radical right hell-bent on oil and gas extraction suggest that the reports of the political elites’ conversion to sobriety were exaggerated, to say the least.

To account for the current regression, we must first identify the actors who structure the debate on climate issues and examine how their arguments and their lobbying succeed in pushing what counts as common sense toward the far-right. While reason used to be on the side of green capitalism, whose promoters claim that the transition to a carbon-free world is as much a priority as it is compatible with the profitability of investments, the mainstream is now being overtaken by two kinds of hardcore climate change deniers: the detractors of an allegedly militant or woke ecology intent on depriving ordinary people of their cars, their meat and their fertilizers, and the apostles of a neo-Malthusian environmentalism predicated on energy sovereignty, closed borders and birth control in the Global South.

On paper, the painless greening and win/win solutions promoted by Net Zero advocates is at odds with the exhortation to “Drill Baby Drill” that serves as the Trump administration's slogan. In practice, however, the differences between the two approaches are often a matter of degree, especially in a context of heightened geopolitical tensions and shifting alliances: compounded with the logic of capital accumulation in fossil fuel and renewable energy sectors, the rivalries that shape industrial policy in the US, Europe, and China tend to subordinate sustainability imperatives to security objectives. Meanwhile older modes of climate change skepticism may be gradually giving way to outright cynicism, as illustrated by the increasing prominence of either bunker mentality or escape to Mars fantasies in far-right circles.

The tipping point that we are reaching calls for both nuance and intransigence. On the one hand, the shortcomings of the COPs should not be confused with the scorched earth policy pursued by their enemies. Yet on the other hand, similarities between crude denialism and strategies of adaptation to climate change cannot be overlooked. This becomes all the more stark as governments ostensibly sensitive to the climate emergency choose to spur investment in risky technologies of geoengineering instead of pivoting away from fossil assets.

The Manufacture of Denial

Interview conducted on 24 September 2025

“If you take away the agencies that play a crucial role in measuring climate change, you don't even have to deny science anymore. You just destroy it. There is something particularly aggressive and tragic about all this. It's really moving into Orwellian territory.”

THE WALL STREET CONSENSUS

Interview conducted on 11 April 2025

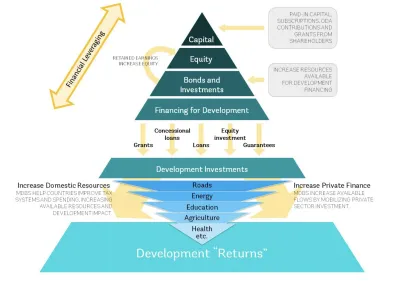

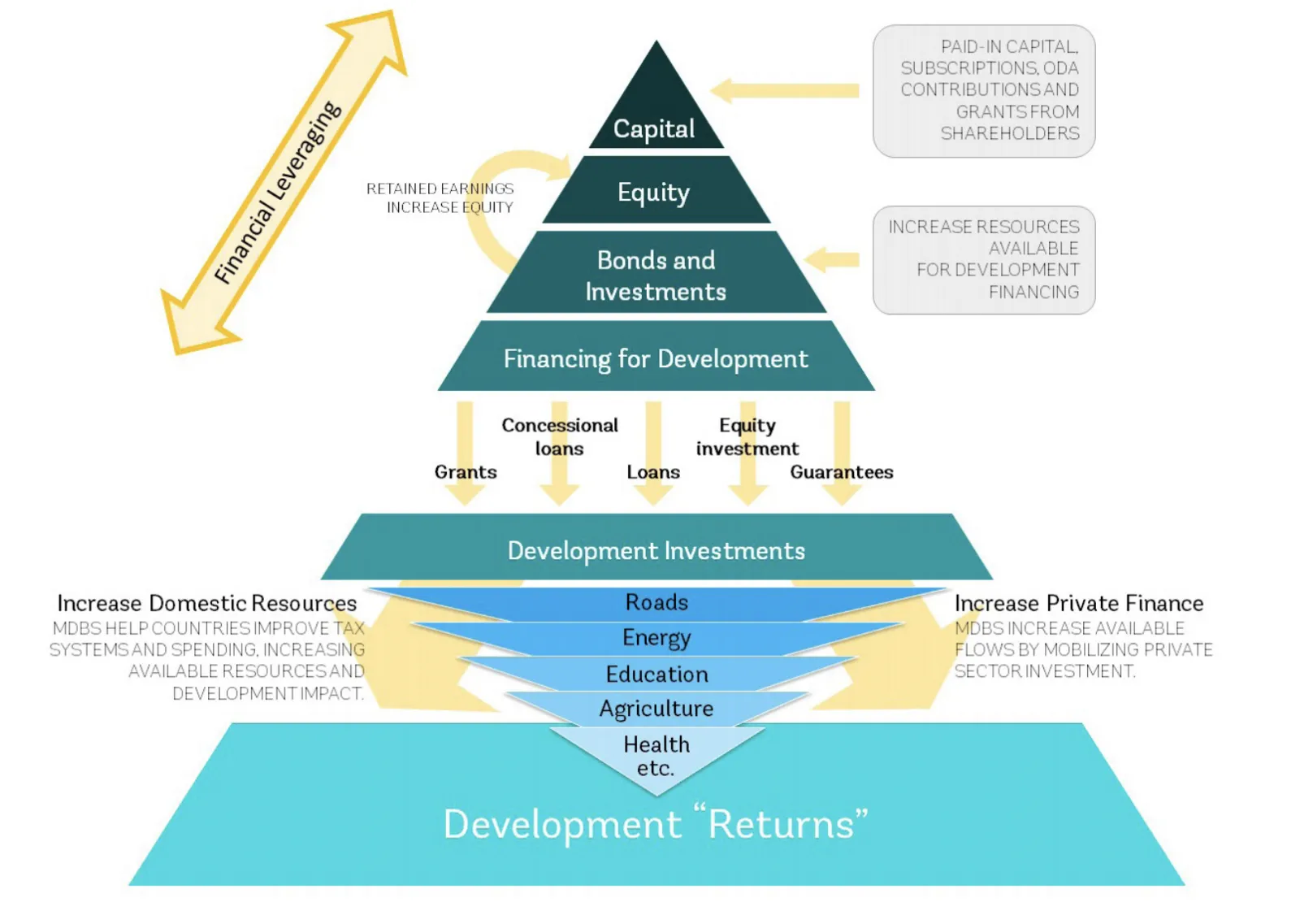

“This is the Wall Street consensus narrative: the state cannot generate enough tax revenue and the private sector cannot generate enough returns for the state's transformative ambitions. The logic of the partnership is therefore to redistribute the risks from the private sector to the state. In this way, the state makes investments in sectors deemed to be priorities, such as development, more attractive to private capital, and this has then spread to climate, industrial policy, armaments, etc."

EXTRACTIVISM, GREEN AND BROWN

Interview conducted on 14 March 2025

"When I talk about green capitalism, it is kind of a mix of productive forces that are already deployed to produce certain products that at least are justified because they have some role in greening the economy, whether that's a lithium battery or lower carbon steel, but also unproven technologies like geoengineering or carbon capture."

Portraits

Scott Bessent

Scott Bessent, who currently serves as Donald Trump’s U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, has no other background in government than the fundraiser he organized for Al Gore in 2000. As a hedge fund manager, however, Bessent definitely has some experience with governments, since he can be credited with “breaking” the Bank of England, by betting against the British pound, back in 1992. At the time, the man who is now Trump’s appointee was a partner at the Soros Management Fund and thus an associate of George Soros, whose philanthropic endeavors figure among the main targets of MAGA’s anti-woke campaigns and whose name is arguably the main code-word for MAGA’s anti-semitic sentiment.

After leaving the Soros management Fund, Bessent co-founded the Key Square Group in 2015 and started embracing the libertarian causes dear to the hedge fund community more wholeheartedly. By 2024, he was one of Donald Trump’s biggest financial backers, donating $1 million to the MAGA Super PAC and another $100,000 to Right for America, another Trumpist Super PAC. He also hosted two fundraisers for Trump, one at his home in Greenville, South Carolina, which raised nearly $7 million and one in Palm Beach, Florida, which raised $50 million.

At his nomination hearing, Bessent praised the fiscal policy that he was appointed to implement and, despite not being cut out for the part, tried his best to give it a populist ring: “If we do not renew these tax cuts,” he warned, “we will be facing an economic calamity, and as always with financial instability that falls on the middle and working class people.”

Though visibly uncomfortable with Donald Trump’s tariff frenzy on “Liberation Day”, Bessent has quietly worked at reconciling his boss’s mercantilist views with Wall Street’s preferences. Hence his carefully crafted speech at the IMF Spring meeting on April 23, 2025, where he sought to reassure US partners by telling them that the administration’s purpose was to reform rather than destroy international institutions like the IMF and the World Bank: “America First does not mean America alone,” he asserted.

At the same time, however, Bessent made sure to remind his audience that the time had come for the IMF and the World Bank to “step back from their sprawling and unfocused agendas, which have stifled their ability to deliver on their core mandates.” What he meant was that the IMF should stop spending “disproportionate time and resources to work on climate change, gender, and social issues”, while “the World Bank must respond to countries’ energy priorities and needs and focus on dependable technologies that can sustain economic growth rather than seek to meet distortionary climate finance targets.”

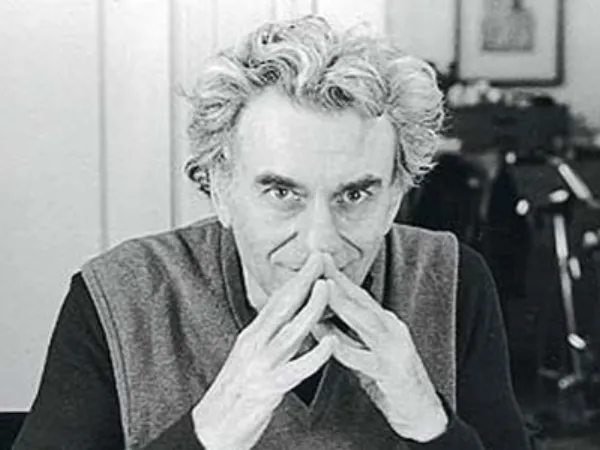

Hyman Minsky

Born in Chicago in 1919, Hyman Minsky grew up in a socialist environment. His parents were both Jewish Mencheviks who came from Belarus after the failure of the 1905 revolution. The story goes that they met in the United States, at a party in honor of the centenary of Karl Marx’s birth. After studying mathematics at the University of Chicago and spending three years working for the US Army in Europe, from 1943 to 1946, the young Hyman began his PhD in economics at Harvard University. He first worked with Joseph Schumpeter and then, after Schumpeter’s death, finished his thesis under the supervision of Wassily Leontief. His interest in cyclical processes owes much to his two mentors.

Minsky’s thought was informed by his reading of John Maynard Keynes—whose Treatise on Probability led him to switch to political economy—but also by his aversion to the neo-Keynesian synthesis that dominated the discipline in the early postwar decades. Marginal even among heterodox macroeconomists, he remained a relatively neglected figure until the 2008 financial crisis brought him posthumous fame. Indeed, the financial crisis was dubbed a “Minsky moment” by mainstream outlets such as The Financial Times, even though the measures taken in response had little to do with what his policy recommendations. While hardly prominent during his lifetime, Minsky did enjoy a distinguished academic career, teaching successively at Brown University, UC Berkeley, and Washington University in St. Louis. After retiring, he ended his research career at Bard College’s Levy Institute, where he continued his work until his death in 1996.1

Minsky belongs to the family of post-Keynesian economists, alongside Michal Kalecki, Joan Robinson, and Nicholas Kaldor. He is the author of two books: John Maynard Keynes, published in 1975,2 in which he takes up the Keynesian concept of radical uncertainty to challenge the sanitization of The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, and Stabilizing an Unstable Economy, published in 1986, which completes his exploration of the structural imbalance that market finance imposes on capitalism.3 The lessons that Minsky draws from his analysis of the 1929 crisis and from Chapter 12 of The General Theory on “The State of Long-Term Expectation” contradict the rational expectations hypothesis on which neoclassical microeconomics is based - and which his rivals in the Keynesian camp largely endorse. He rejects the idea that economic agents have a constant aversion to risk, i.e., one that is independent of the economic conjuncture. According to Minsky, decision-making in a context of radical uncertainty leads to a “procyclical” alternation between moments of enthusiasm and anxiety. It therefore gives financial markets an irremediably manic-depressive character.

When the capitalist economy enters a period of growth, the proponent of the “paradox of tranquility” explains, the newfound confidence encourages companies to invest, first with their own equity, but then by borrowing. No less inclined to optimism, lenders and other institutional investors willingly respond to requests made of them, betting that borrowers’ boldness is a sign of significant returns on investment. Initially, however, interactions between non-financial firms and credit providers remain within what Minsky calls the “hedge finance” stage: the former limit themselves to borrowing sums that they are able to repay, and the latter exercise the same caution in their largesse.

But soon, the continued growth prospects signaled by rising stock prices and bond values will push economic agents to take more risks. They will start by borrowing and lending when borrowers can only pay interest and refinance the principal by borrowing again. This is the stage of “speculative finance”, where blindness is based on the fact that the fear of missing out on the opportunity to make profits, and even more so of letting others reap the benefits of one's own timidity, exceeds the fear of defaulting on payments.

This phase of excited “animal spirits”, to borrow Keynes’ expression, culminates in what Minsky calls “Ponzi finance”, named after the famous swindler Carlo Ponzi, who offered exceptional returns to his oldest clients by drawing on the funds brought in by the newest ones. At this stage, the rise in the price of financial assets continues, but is no longer based on the accumulation of income from production. In other words, borrowers can no longer repay anything, neither principal nor interest, but continue to seek more funds.

From then on, the first signs of a trend reversal begin to appear: running out of cash, some security holders are forced to sell the securities they hold. Their sudden change in attitude does not fail to alert their colleagues and clients, who are quick to follow suit. As the quest for liquidity spreads, panic replaces exuberance. No less procyclical than confidence, fear of bankruptcy quickly means that there are no more buyers for depreciated securities. Thus, the crash and its consequences, recessionary or even depressive, become inevitable.

Of course, Minsky is not the only economist to have studied the mechanisms that lead to financial crises. However, he differs from his predecessors, with the exception of Keynes, in that he views the sequence of three stages—hedged finance, speculative finance, and Ponzi finance—as a process inherent to capitalism, whose explosive nature intensifies as capitalism develops. Indeed, it is the increase in productivity and the lengthening of periods of growth that fuel the denial of the capitalist mode of production’s structural instability—a denial expressed by neoclassical economists’ faith in bounded uncertainty—and, consequently, considerably worsen the impact of the “paradox of tranquility” on the lives of the majority.

According to Minsky, there is no corrective force capable of restoring balance or even tempering the “bipolar” nature of capitalism. He therefore believes that stabilizing an unstable economy depends on government intervention. Only elected governments, Keynes already argued, have any reason to be concerned about the long term and the impact of growing inequality on the prosperity of the nations they govern. The author of John Maynard Keynes obviously agrees with his mentor. However, his view of what public action should consist of si going to evolve somewhat between his first and his second book.

More radical until the neoliberal shift of the 1980s, Minsky was not far from believing that the only way to stabilize capitalism was to exit from it, albeit gradually. On this point, he agreed with Joan Robinson, whom he met during a year spent at Cambridge. Skeptical about the effectiveness of fiscal redistribution and highly critical of the Johnson administration’s “war on poverty”, which he saw as a charitable way of maintaining the status quo, he believed that the issue of employment was the decisive factor. True to a Keynesianism that makes full employment, rather than growth, the goal of macroeconomic policy, Minsky believed that it was up to the state to act as the employer of last resort and that the central bank should configure its role accordingly. In his view, the growth of the public sector and what employers refered to as “financial repression” were the only means of curbing capitalism’s propensity for speculation.

The success of the neoliberal counter-revolution, and even more so the collapse of the Soviet empire, would however change, if not Minsky’s analyses, at least the remedies he considered appropriate in a context where, as the famous saying goes, it is harder to imagine the end of capitalism than the end of the world. Already in Stabilizing an Unstable Economy, and even more so in his later writings, Minsky focused less on increasing public sector jobs and more on decreasing the concentration of the private sector. The main task he assigned to regulators and central bankers was now to ensure the viability of small and medium-sized enterprises by promoting the creation of a myriad of small banks committed to contributing to local and regional development. In other words, for the late Minsky, and much to the dismay of proponents of a Marxist-Keynesian synthesis, “stabilizing an unstable economy” ceased to be an ironic proposition.

1 https://www.bard.edu/library/a...

2 Hyman Minsky, John Maynard Keynes, (New York, Columbia University Press), 1975

3 Hyman Minsky, Stabilizing an Unstable Economy, (New York, McGraw-Hill), 2008; traduction française: Stabiliser un économie instable, préface d’André Orléan, postface de Michel Aglietta (Paris, Les petits matins/institute Veblen), 2016.

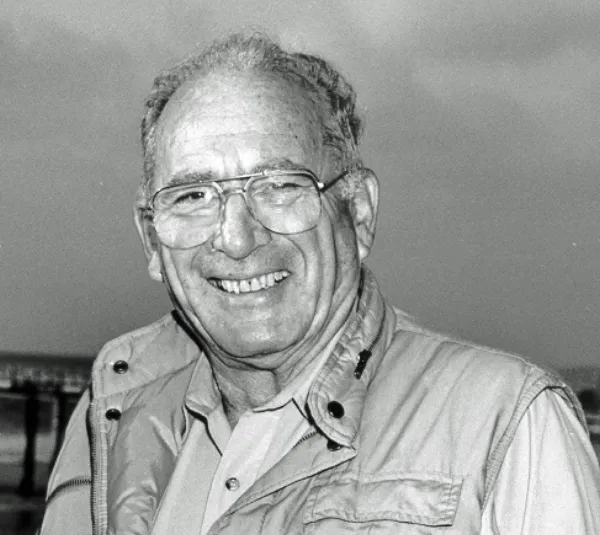

Lee Raymond

Lee R. Raymond (born 1938) led Exxon and later ExxonMobil from 1993 to 2005, overseeing the company during a decisive period in the global climate debate. Although Exxon’s own scientists had confirmed by the early 1980s that fossil fuel combustion would cause significant warming, Raymond publicly questioned these findings once he became CEO. Internal reports from as early as 1982 warned of major climatic changes, yet under Raymond’s leadership, ExxonMobil adopted a markedly skeptical stance toward human-caused climate change.

Throughout the 1990s, Raymond was one of the most outspoken corporate opponents of emerging climate policy. At the 1997 World Petroleum Congress in Beijing, just before the Kyoto Protocol negotiations, he claimed “the case for so-called global warming is far from air-tight,” arguing that natural variability explained observed temperature changes and that emissions cuts would defy “common sense.” As chair of the American Petroleum Institute, he advanced messaging that emphasized scientific uncertainty. Exxon under his direction funded think tanks and advocacy groups—spending nearly $20 million between 1997 and 2005—that promoted climate skepticism and delayed policy action.

In a 2005 Charlie Rose interview, Raymond reiterated his central arguments: that Earth’s climate has always changed naturally, that science had not proven human influence, and that consensus does not equal truth—famously comparing belief in global warming to “when 90 percent of people thought the world was flat.” He maintained that acting on incomplete science would harm the economy and that there was still “time to understand the issue better.”

Raymond’s ExxonMobil became emblematic of corporate obstruction of climate action. While competitors like BP began acknowledging climate risks in the late 1990s, Exxon doubled down on skepticism. Following Raymond’s retirement, the Royal Society and others condemned ExxonMobil’s misleading communications, and by 2008 the firm quietly ended funding for some denial groups.

Historians now regard Raymond as a pivotal figure in shaping late-20th-century climate discourse. His leadership strengthened industry opposition to emissions policy, amplified public doubt, and helped delay global action for a decade or more. The “Raymond era” stands as a cautionary example of how corporate strategy and persuasive rhetoric can obstruct scientific consensus and policy progress.

William A. Nordhaus

According to the French economist Antonin Pottier, William Nordhaus’s intellectual trajectory begins paradoxically with his critique of the Club of Rome report The Limits to Growth, published in 1972. The report questioned the sustainability of economic growth, arguing that resource depletion and pollution would eventually constrain global development. At the time, Nordhaus was a young professor at Yale University and already a proponent of mainstream economics. He analyzed the report critically, emphasizing its lack of empirical grounding. Among the various problems identified as potential causes of collapse, Nordhaus singled out climate change as the only one likely to produce serious macroeconomic consequences within the coming century.

From 1974 onward, Nordhaus turned his attention specifically to the economics of climate change. His first quantitative contribution came in 1977, when he proposed an early cost-effectiveness analysis. Using an energy system model and a carbon-cycle model, he estimated the costs associated with different targets for stabilizing atmospheric CO₂ concentrations. Since no established benchmark existed, he relied on his own judgment to select these targets, considering a doubling of CO₂ concentration (around 550 ppm) a prudent upper limit that should not be exceeded.

Nordhaus, however, grew dissatisfied with what he regarded as the arbitrariness of this approach. He believed that climate objectives could not rest on subjective preferences or moral principles but had to be determined “scientifically,” through calculation itself. This conviction led him, during the 1980s, to move from cost-effectiveness to cost-benefit analysis, an approach aimed at identifying the optimal level of emissions reduction that maximizes net social welfare by balancing mitigation costs against the benefits of avoided damages.

His new intellectual outlook led him to develop the DICE model (Dynamic Integrated Model of Climate and the Economy), finalized in the early 1990s. DICE became the canonical integrated assessment model of climate economics. Built as a simplified extension of the neoclassical model of optimal growth, it conceives emissions reductions as investments in the future that should yield the same rate of return as other productive investments. The goal is to determine the optimal investment path, which leads to the calculation of an “optimal level of global warming,” the amount of climate change that a rational economic agent should be willing to accept.

Because of Nordhaus’s central position within the discipline and the model’s simplicity, derived from well-known optimal growth frameworks, DICE spread rapidly and became the dominant analytical tool for climate policy among economists. By situating climate evaluation within the framework of intertemporal consumption optimization, Nordhaus placed the economist at the heart of the climate problem, turning him into both the arbiter of intergenerational wealth transmission and a judge balancing two imperatives: minimizing economic costs and limiting global warming.

As Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway have shown, however, the legacy of William A. Nordhaus is also part of the history of the organized delay affecting climate action. Nordhaus notably co-authored, with Jesse Ausubel and Gary Yohe, the first chapter of the third climate report issued by the National Academy of Sciences in 1983, chaired by William Nierenberg. Their contribution on Energy Use and Carbon Dioxide Emissions began by acknowledging the “widespread agreement that anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions have been rising steadily, primarily driven by the combustion of fossil fuels.” Their focus, however, was not on what was known, but on what was not known: the “enormous uncertainty beyond 2000, and the even greater uncertainty about the social and economic impacts of possible future trajectories of carbon dioxide.”

Using probabilistic scenario analysis, they projected atmospheric CO₂ levels to 2100 under varying assumptions regarding energy use, costs, and economic efficiency. The range of possible outcomes was large, but they considered the most likely scenario to be CO₂ doubling by 2065. The economists acknowledged the “substantial probability that doubling will occur much more quickly,” including a 27 percent chance that it would occur by 2050, and admitted that “it was unwise to dismiss the possibility that a doubling may occur in the first half of the twenty first century.” Yet, as Oreskes and Conway note, they effectively did just that.

What could be done to stop climate change? According to Nordhaus, not much. “The most effective action would be to impose a large permanent carbon tax,” he wrote, “but that would be hard to implement and enforce.” As the report continued:

“A significant reduction in the concentration of CO₂ will require very stringent policies, such as hefty taxes on fossil fuels... The strategies suggested later in the report by Schelling, climate modification or simply adaptation to a high CO₂ and high temperature world, are likely to be more economical ways of adjusting... Whether the imponderable side effects on society, on coastlines and agriculture, on life in high latitudes, on human health, and simply the unforeseen, will in the end prove more costly than a stringent abatement of greenhouse gases, we do not now know.”

In this way, Nordhaus’s contribution to the 1983 NAS report exemplified a broader tendency within United States climate policy discourse: to acknowledge scientific consensus while simultaneously emphasizing uncertainty, advocating delayed action, and framing adaptation and technological innovation as preferable to immediate mitigation.

Building on this critique, Jean Baptiste Fressoz situates Nordhaus within a broader history of modernist economic optimism that merges the economics of innovation with the techno political imagination of the atomic age. In Sans transition (2024), Fressoz describes Nordhaus as “one of the atomic futurologists of the 1970s,” whose confidence in technological progress, especially nuclear energy and the breeder reactor, underpinned the very concept of energy transition. In a 1973 paper, Nordhaus even argued that conservation efforts might be excessive, since “technological progress would soon solve the energy crisis.” He predicted that by the end of the twenty first century, the global economy would run on hydrogen and electricity derived from infinite resources, the “final stage of transition.” The breeder reactor, he wrote, would serve as a “backstop technology,” a technological safety net later reinterpreted in his climate models.

During his stay at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis between 1974 and 1975, Nordhaus encountered the Italian engineer Cesare Marchetti, who introduced him to climate modeling. Together, they imagined a world of inexhaustible energy and geoengineering possibilities. Nordhaus developed a simple mathematical model to maximize global GDP while avoiding CO₂ doubling, concluding that humanity had “comfortable time” to act. As Fressoz notes, “the optimal trajectory did not initially differ from the uncontrolled one,” a result that became central to his later economic reasoning.

Fressoz further points out that Nordhaus’s influence extended far beyond academia. Exxon, for instance, drew directly on Nordhaus’s claim that there was “sufficient time” for an “orderly transition” to justify continued fossil fuel extraction. In the 1990s, Nordhaus’s DICE model came to dominate Working Group III of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, institutionalizing a logic of procrastination. DICE’s purpose was to calculate the economically optimal temperature of the Earth, which Nordhaus estimated at 3.5 degrees Celsius, a level he deemed compatible with continued prosperity for “a technological and nomadic species” (Homo adaptus).

For Fressoz, Nordhaus thus represents the culmination of a modernist faith in innovation and market mechanisms that has systematically underestimated material constraints and the inertia of the energy system. By confounding technology with innovation, Nordhaus and his followers have sustained the belief that economic growth and decarbonization can progress hand in hand. In Fressoz’s words, such reasoning “provided the intellectual tools for procrastination,” legitimizing political delay while introducing “fantastical technological options,” such as geoengineering, into mainstream climate scenarios.

Sources :

Antonin Pottier, Comment les économistes réchauffent la planète, Seuil, 2016.

Naomi Oreskes et Erik M. Conway, Merchants of Doubt, Bloomsbury Press, 2010.

Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, Sans transition, Seuil, 2024.

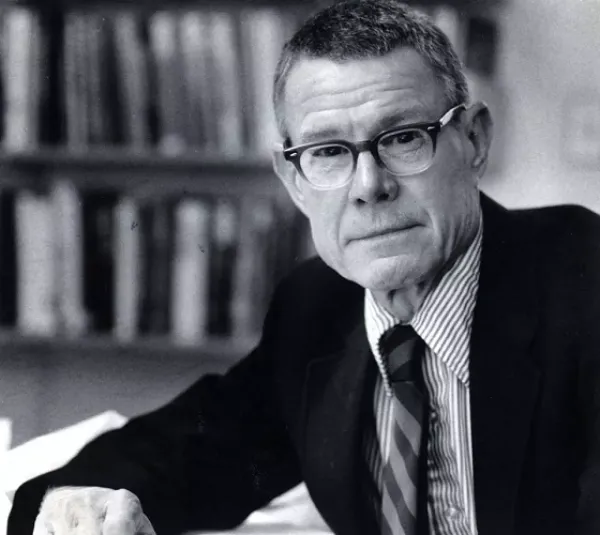

Thomas C. Schelling

Thomas C. Schelling (1921–2016) was a prominent economist and strategist best known for his contributions to game theory and the economics of conflict and cooperation. A central architect of Cold War rationality, he helped develop the doctrine of nuclear deterrence through his seminal work The Strategy of Conflict (1960), which analyzed bargaining as a process of gaining advantage through threats rather than direct force. He also introduced the notion of the “focal point,” the tacit equilibrium that adversaries agree to respect to avoid mutually assured destruction.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Schelling transposed this logic of strategic rationality to the emerging issue of anthropogenic climate change. He chaired the National Academy of Sciences’ 1980 study on the social and political dimensions of global warming and later served on the 1983 Carbon Dioxide Assessment Committee, which produced the report Changing Climate: Report of the Carbon Dioxide Assessment Committee, under the supervision of William A. Nierenberg. Contrary to National Academy conventions, this report was not collectively signed due to internal disagreements and, in effect, consisted of two reports: five chapters, written by natural scientists, addressed the likelihood of anthropogenic climate change, while two chapters on emissions and impacts were authored by economists, including William Nordhaus and Thomas Schelling.

This new report largely responded to what Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway describe as the “seminal year for climate,” 1979. That year, MIT meteorologist Jule Charney—one of the founders of modern numerical atmospheric modeling—assembled a panel of eight other scientists at the Academy’s summer study facility in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. He invited Syukuro Manabe from the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory and James E. Hansen from the Goddard Institute for Space Studies to present the results of their new three-dimensional climate models. The key question in climate modeling was “sensitivity”: how sensitive the climate is to changing levels of CO₂. If you double, triple, or even quadruple CO₂, what average global temperature change should you expect? The state-of-the-art answer, for the convenient case of doubling CO₂, was “near 3°C with a probable error of 1.5°C.” That meant total warming might be as little as 1.5°C or as much as 4°C, but either way, there would be warming—and the most likely value was about 3°C. The Charney Report concluded: “If carbon dioxide continues to increase, the study group finds no reason to doubt that climate changes will result and no reason to believe that these changes will be negligible.”

Verner E. Suomi, chairman of the National Academy’s Climate Research Board, underscored this crucial point in his foreword: “The ocean, the great and ponderous flywheel of the global climate system, may be expected to slow the course of observable climatic change. A wait-and-see policy may mean waiting until it is too late.” Suomi realized that this conclusion might be “disturbing to policymakers.”

Indeed, this proved correct, since even before the report was published, the White House Office of Science and Technology had already begun requesting further information from the National Academy. The second Academy study, sent as a letter to the White House in April 1980, was chaired by Schelling.

Arguing that there were enormous uncertainties about both climate change and its potential costs, Schelling advised that policymakers should refrain from taking immediate action and instead fund further research. He was not convinced that all the effects of warming would be harmful. “The credible range of effects is extremely broad,” he wrote. “By the middle of the next century, we may have a climate almost as different from today’s as today’s is from the peak of the last major glaciation. At the other extreme, we may only experience noticeable but not necessarily unfavorable effects around mid-century or later.”

Schelling maintained that climate change would not produce new types of climate but would simply shift the distribution of climatic zones across the Earth. This idea foreshadowed a recurring argument of later climate skeptics: that humanity could continue to burn fossil fuels without restriction and deal with the consequences through migration and adaptation. Schelling noted that past human migrations “to and throughout the New World subjected large numbers of people—together with their livestock, food crops, and culture—to drastically changed climate.” Although he acknowledged that these migrations occurred in eras without modern political boundaries, he nevertheless suggested that adaptation would be the best response.

He argued that there was sufficient time to prepare and that during this interval, the rising cost of fossil fuels would naturally curb their consumption. “The slowing rate of fossil fuel use,” he wrote, “will make adaptation to climate change easier and may permit more absorption of carbon into non-atmospheric sinks. It will also permit conversion to alternative energy sources at a lower cumulative carbon dioxide concentration, and it is likely that the sooner we begin the transition from fossil fuels the easier the transition will be.” All of this, Schelling believed, would occur spontaneously as market forces took effect, making regulation unnecessary.

Given the numerous uncertainties he emphasized, Schelling’s faith in market self-correction was striking. Fossil fuel use has, in fact, risen dramatically over the past four decades, even as global warming has accelerated. Yet had his prediction been correct, there would indeed have been no need for government intervention. Consequently, the panel did not recommend any program of emissions reductions, despite acknowledging that “the sooner we begin the transition, the easier it will be.” Instead, they concluded:

“In view of the uncertainties, controversies, and complex linkages surrounding the carbon dioxide issue, and the possibility that some of the greatest uncertainties will be reduced within the decade, it seems to most of us that the near-term emphasis should be research, with as low a political profile as possible... We do not know enough to address most of these questions right now. We believe that we can learn faster than the problem can develop.”

Following this debate, meteorologist John Perry published a response in Climatic Change with the programmatic title “Energy and Climate: Today’s Problem, Not Tomorrow’s,” arguing that delay carried its own risks.

The third Academy assessment was the 1983 report Changing Climate. Whereas the chapters written by natural scientists—addressing topics such as climate dynamics, water availability, and marine ecosystems, and including Roger Revelle’s warning about sea-level rise from the potential disintegration of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet—emphasized the serious consequences of unmitigated warming (while acknowledging the need for continued research to reduce uncertainties), the chapters authored by economists, as well as the report’s synthesis, adopted a cautious “wait-and-see” approach. The first chapter, written by William Nordhaus, Jesse Ausubel, and Gary Yohe, acknowledged the “widespread agreement that anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions have been rising steadily, primarily driven by the combustion of fossil fuels.” However, the authors emphasized the “enormous uncertainty” beyond 2000 and the “even greater uncertainty” regarding the “social and economic impacts of possible future trajectories of carbon dioxide.” The economists assumed that serious changes could be discounted into the future. Nordhaus thus called for the implementation of a permanent carbon tax as a market-based solution to rising emissions.

This argument was echoed by the final chapter, written by Schelling. His logic of climate discounting stipulated that climate change was “beyond the lifetimes of contemporary decision-makers.” Schelling argued against isolating CO₂ emissions from other variables such as dust, land-use changes, and natural variability, maintaining that it would be mistaken to assume a “preference for ... dealing with causes rather than symptoms... It would be wrong to commit ourselves to the principle that if fossil fuels and carbon dioxide are where the problem arises, that must also be where the solution lies.”

The synthesis of the report, written by Nierenberg, followed the economists’ line: “Viewed in terms of energy, global pollution, and worldwide environmental damage, the CO₂ problem appears intractable,” it stated, but “viewed as a problem of changes in local environmental factors—rainfall, river flow, sea level—the myriad of individual incremental problems take their place among the other stresses to which nations and individuals adapt.” Nierenberg argued that the potential uninhabitability of certain regions due to rising sea levels could be offset by migration: “Not only have people moved,” he observed, “but they have taken with them their horses, dogs, children, technologies, crops, livestock, and hobbies. It is extraordinary how adaptable people can be.”

Nierenberg’s report aligned perfectly with the expectations of the White House. It downplayed scientific disagreements, suggested broad consensus between scientists and economists, and argued that technological innovation would solve future problems. Finally, it concluded that no immediate regulatory action was necessary beyond funding additional research.

The White House subsequently deployed Nierenberg’s report to undermine the Environmental Protection Agency’s emerging climate assessments. The EPA had issued two reports concluding that global warming posed a serious threat and that immediate action was required to reduce coal consumption. In response, Presidential Science Advisor George Keyworth invoked the Nierenberg panel’s findings to discredit the EPA’s conclusions, reporting that “the Science Advisor has discredited the EPA reports … and cited the NAS (National Academy of Sciences) report as the best current assessment of the CO₂ issue,” adding that the press had largely dismissed “EPA alarmism” in favor of “the conservative NAS position.”

The environmental philosopher Pierre Charbonnier’s reading of Thomas C. Schelling departs from the line developed by Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway in the history of organized climate denial. For Oreskes, Schelling can be listed among those experts who lent intellectual cover to a strategy of delaying action by stressing uncertainty and national interest. Charbonnier does not dispute this, but he argues that this is only half the story: Schelling was influential not simply because he minimized risk, but because he succeeded in translating climate change into the language of power, security, and strategic bargaining — a language state elites were already using. In other words, even without fossil-fuel lobbying, his framework would have been attractive to governments.

Charbonnier reconstructs Schelling’s climate paradigm around three principles. First, risk is subordinate to adaptive capacity: climate change is real but slower than technological progress and therefore manageable in the long run, mainly through future innovation; its effects will be uneven and will track global inequalities. Second, fully binding, universal carbon agreements are structurally unlikely, because climate change is entangled with energy security and geopolitical rivalry; states will not sacrifice sovereignty for what is framed as a secondary risk. Third, climate policy becomes a permanent negotiation, analogous to arms-control talks, aimed at finding an “optimal” level of warming. This is the climatic equivalent of Schelling’s nuclear “focal point”, beyond which emissions turn from economically positive to strategically dangerous.

To name this fusion of deterrence thinking, cost–benefit reasoning, and fossil developmentalism, Charbonnier speaks of “Strangelove ecology”: an ecology that does not challenge the strategic premises of the Cold War state but uses them to make climate governable. Its power, he stresses, lies in offering a ready-made geo-economic synthesis to decision-makers, something most normative environmentalism has failed to do.

Sources : Naomi Oreskes et Erik M. Conway, Merchants of Doubt, Bloomsbury Press, 2010, chap. 6; Pierre Charbonnier, Vers l’écologie de guerre, La Découverte, 2024, chap. 5.

Roger Revelle

Roger Revelle (1909–1991) was an eminent oceanographer and climate scientist, recognized for his pivotal role in the history of climate research and for his influence as a mentor to future U.S. Vice President Al Gore, who studied with him at Harvard in the 1960s.

Revelle’s interest in global climate change deepened in the late 1950s, when he co-authored with Hans E. Suess the seminal paper “Carbon Dioxide Exchange Between Atmosphere and Ocean and the Question of an Increase of Atmospheric CO₂ During the Past Decades.” The study demonstrated that the oceans could not absorb all anthropogenic carbon dioxide, implying that atmospheric concentrations would inevitably rise as a consequence of fossil-fuel combustion. Shortly thereafter, Revelle secured funding for his colleague, chemist Charles David Keeling, to conduct systematic measurements of atmospheric CO₂. This foundational research produced the now-famous Keeling Curve—showing CO₂’s steady increase over time—for which Keeling would later receive the National Medal of Science and be made famous by Al Gore in An Inconvenient Truth.

In 1965, the President’s Science Advisory Committee asked Revelle, then director of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, to write a summary of the potential impacts of carbon-dioxide-induced warming. Revelle knew that there was much about the problem that remained uncertain, so he focused his essay on the impact he considered most certain: sea-level rise. He also made a striking forecast: “By the year 2000 there will be about 25% more CO₂ in our atmosphere than at present [and] this will modify the heat balance of the atmosphere to such an extent that marked changes in climate... could occur.”

Two decades later, Revelle contributed a chapter to Changing Climate: Report of the Carbon Dioxide Assessment Committee (1983), a study supervised by William A. Nierenberg. In this report, he again warned that the disintegration of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could trigger a global sea-level rise of five to six meters: “The oceans,” he stated, “would flood all existing port facilities and other low-lying coastal structures, extensive sections of the heavily farmed and densely populated river deltas of the world, major portions of the states of Florida and Louisiana, and large areas of many of the world’s major cities.” Regarding mitigation, Revelle advocated a pragmatic transition toward natural gas and nuclear energy while phasing down coal and oil, emphasizing the importance of sustained research and the dangers of overstating uncertainty.

Revelle became the focus of controversy in the early 1990s when a small group of scientists claimed he had reversed his position on global warming. The claim stemmed from an article co-authored with S. Fred Singer and Chauncey Starr, titled “What to Do About Greenhouse Warming: Look Before You Leap,” published in 1991 in Cosmos: A Journal of Engineering and Science, the journal of Washington’s exclusive Cosmos Club. Listed as second author, Revelle appeared to endorse the view that the most probable warming over the next century would be modest—less than one degree Celsius.

The article, however, was a source of embarrassment for Revelle. Cosmos was not a peer-reviewed scientific journal, and colleagues reported that Revelle privately dismissed the piece as “garbage.” Oceanographer Walter Munk noted that Revelle was known for his reluctance to refuse requests and suggested that he had not explicitly agreed to be listed as co-author. Revelle’s longtime secretary, Christa Beran, later testified in an affidavit that Revelle had commented, “Some people don’t think Fred Singer is a very good scientist.”

The episode coincided with the final months of Revelle’s life and placed him under considerable stress. In February 1991, he suffered a major heart attack while returning to La Jolla from a conference, which required a triple-bypass operation. After a series of postoperative complications and infections, his health deteriorated further, leaving him too weak to continue regular correspondence or mentoring. He died of a second heart attack in July 1991. The Cosmos article was subsequently exploited during the 1992 U.S. presidential campaign to discredit Al Gore by portraying Revelle as having renounced the very warnings about climate change he had helped to pioneer.

Source : Naomi Oreskes et Erik M. Conway, Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming, New York, Bloomsbury Press, 2010.

Siegfried Fred Singer

Siegfried Fred Singer (1924–2020) was a physicist and political entrepreneur whose career spanned upper-atmosphere research, satellite meteorology, and later interventions in environmental policy debates. As shown in Merchants of Doubt, his trajectory illustrates how Cold War scientific authority was repurposed to contest regulation by emphasizing uncertainty, costs and market solutions. Trained as a physicist during the Second World War, he gained recognition in the 1950s for rocket studies of cosmic rays and the Earth’s magnetic field and emerged as an early advocate of scientific satellites. He later directed the National Weather Satellite Center and held policy posts in the Nixon and Reagan administrations, positioning himself at the intersection of science and government.

In 1970 Singer appeared as an eco-Malthusian environmentalist. At an AAAS symposium he invoked Garrett Hardin’s well-known 1968 article on the “Tragedy of the Commons” and argued that environmental protection was necessary. In a 1971 book on population he described the risks of unchecked growth and endorsed precautionary measures. By the late 1970s, however, his views shifted. A Mitre Corporation report advocated cost–benefit analysis as the arbiter of environmental regulation and emphasized the heavy costs of pollution control relative to uncertain benefits. By the early 1980s Singer had moved toward a free-market, Cornucopian view in which technological innovation, spurred by deregulation, would obviate ecological constraints.

Singer’s ideological shift became visible in the acid rain controversy. When the Reagan administration bypassed the National Academy and commissioned its own review in 1982–83, William A. Nierenberg was appointed chair. At the White House’s request, Singer was added to the panel, the only member without a full-time academic affiliation. The panel’s consensus text concluded that sulfur dioxide emissions were the dominant cause of acid deposition and that reductions should begin immediately despite uncertainties. Singer dissented, producing a separate appendix that stressed residual scientific doubt, highlighted the costs of emissions controls, and advocated a least-cost trial before serious abatement. His framing resonated with utility industry arguments and helped justify regulatory delay. The Executive Summary was reordered and softened in consultation with the Office of Science and Technology Policy, ensuring that uncertainty appeared first. Singer later claimed that postponing action saved billions per year.

Singer also disputed the scientific basis of stratospheric ozone depletion, suggesting that the Antarctic ozone hole could be explained by stratospheric cooling and natural variability rather than chlorofluorocarbon emissions, thereby reversing the conclusions of mainstream atmospheric chemistry. He further contested the findings of the U.S. Surgeon General and the Environmental Protection Agency, claiming that their reviews were politically motivated. His anti-EPA report, funded via the Tobacco Institute through the Alexis de Tocqueville Institution, exemplified the alignment of his interventions with corporate interests.

Singer became a public critic of mainstream climate science in the late 1980s and 1990s, stressing that uncertainties made costly measures premature. In 1991, he co-authored an article with Roger Revelle and Chauncey Starr in Cosmos titled “What to Do About Greenhouse Warming: Look Before You Leap.”1 Archival evidence and testimony indicate that Revelle, frail from heart surgery, was reluctant and only minimally involved. The published article nonetheless implied that global warming would likely be modest and not significantly different from natural variability, contrary to the consensus Revelle and Hans Suess had helped to establish in their seminal 1957 article Carbon Dioxide Exchange Between Atmosphere and Ocean2 and the Question of an Increase of Atmospheric CO₂ during the Past Decades. During the 1992 U.S. presidential campaign the Cosmos piece was weaponized to discredit Al Gore, Revelle’s former student. When Justin Lancaster, a graduate student close to Revelle, publicly disputed Singer’s portrayal, Singer sued him for libel, resulting in a gag order and settlement.

By the mid-1990s, climate science had advanced to detection-and-attribution studies. Using “fingerprinting” techniques, scientists such as Benjamin Santer demonstrated that observed atmospheric warming patterns were consistent with greenhouse forcing and inconsistent with natural variability alone. In 1995 Santer, together with Tom Wigley and others, authored Chapter 8 of the IPCC’s Second Assessment Report, concluding that “the balance of evidence suggests a discernible human influence on global climate.” This statement galvanized opposition. Singer, along with Frederick Seitz and other members of the Marshall Institute network, attacked the IPCC process in Science, the Wall Street Journal and other outlets. He accused Santer of having altered the report after its acceptance in Madrid, of suppressing uncertainties, and of excluding dissenting voices such as Patrick Michaels. These charges were false: the revisions were mandated by IPCC procedure, uncertainties were explicitly included, and Michaels had been invited to contribute but declined. Nonetheless, the accusations gained traction in political and media arenas. Seitz accused Santer of “corruption of the peer-review process,” and Singer repeated claims of “scientific cleansing.” Professional societies and leading scientists publicly defended Santer and the IPCC process, but the campaign nevertheless reinforced the impression that anthropogenic climate change remained unsettled, providing political cover for inaction.

Singer’s intellectual trajectory intersected with the Cornucopian philosophy of Julian Simon. Simon’s insistence that human ingenuity would indefinitely expand resources and improve living standards found echoes throughout Singer’s interventions. Singer himself had been vexed by apocalyptic claims since 1970, when in a Science editorial he argued that fossil-fuel combustion would not yield serious warming because aerosol cooling would counterbalance the greenhouse effect. His warning to scientists was “not to cry wolf needlessly or too often.” While aerosols did indeed mask early warming, Singer dismissed the possibility that continued CO₂ accumulation would eventually overwhelm them.

In the 1980s Singer recognized that Cornucopian arguments presupposed abundant, affordable energy, but he soon dropped this caveat. By the 1990s he was firmly aligned with Simon’s worldview. His 1999 book Hot Talk, Cold Science: Global Warming’s Unfinished Debate, introduced by Seitz and published by the Independent Institute (where Simon served as an advisor), exemplified this orientation. He also contributed to Simon’s edited volume The State of Humanity alongside Patrick Michaels and Laurence Kulp.

Singer’s career thus went through a shift from Cold War physicist to organized denier. His scientific credentials, once central to the institutionalization of satellite meteorology, became tools in campaigns that delayed regulation of acid rain, ozone-depleting chemicals, tobacco smoke, and greenhouse gases. He did not typically deny phenomena outright; instead he magnified uncertainties, stressed economic costs, and promoted market mechanisms. Alongside Seitz, Nierenberg, and Jastrow, he became one of the central architects of organized climate skepticism—an enduring merchant of doubt.

1 Revelle, Roger, Chauncey Starr, and S. Fred Singer. “What to Do About Greenhouse Warming: Look Before You Leap.” Cosmos: A Journal of Engineering and Science 5, no. 2 (1991): 28–33.

2 Revelle, Roger, and Hans E. Suess. “Carbon Dioxide Exchange Between Atmosphere and Ocean and the Question of an Increase of Atmospheric CO₂ During the Past Decades.” Tellus 9, no. 1 (1957): 18–27.

Source : Naomi Oreskes et Erik M. Conway, Merchants of Doubt. How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming, New York, Bloomsbury Press, 2010.

William A. Nierenberg

William Aaron Nierenberg (1919–2000) was a physicist of the Cold War generation whose authority and political commitments made him a key figure in the Reagan administration’s handling of environmental science. Trained at Columbia University during the Manhattan Project, he later directed Columbia’s Hudson Laboratories and in 1965 became director of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, where he consolidated strong ties between oceanography and military-funded research.

By the 1970s Nierenberg had established himself as both a prominent administrator and an outspoken conservative. He defended the Vietnam War, criticized the student movement and took a combative stance toward environmentalism, particularly in its opposition to nuclear power. These positions made him a precious asset for Ronald Reagan’s agenda. He served on the administration’s transition teams, was considered for the post of science advisor, joined the National Science Board, and was repeatedly consulted on defense and energy issues.

His most consequential role came during the acid rain controversy of the early 1980s. By then, extensive research in North America and Europe had shown that sulfur dioxide emissions from coal and oil were the principal cause of acid precipitation. Reports by the National Academy and the Environmental Protection Agency called for sharp emission reductions. Confronted with these findings as well as the prospect of costly regulation, the Reagan White House commissioned a new review under the Office of Science and Technology Policy, appointing Nierenberg as chair.

The “Nierenberg panel” largely confirmed the scientific consensus that acid rain was real, anthropogenic, and damaging, and recommended beginning emissions reductions without further delay. Once drafted, however, the report was altered under political pressure. At the insistence of the White House, Fred Singer was added to the panel and produced a dissenting appendix stressing uncertainty and costs. More significantly, the Executive Summary that policymakers would read was revised in consultation with White House officials. Strong language calling for abatement was softened, uncertainty emphasized, and progress under existing laws highlighted. Several panelists protested against these unauthorized changes, but Nierenberg allowed them to stand, giving the administration cover to postpone action.

In the short run, his authority helped Reagan block congressional initiatives, stall bilateral negotiations with Canada, and delay substantive regulation until the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments. In the longer run, Nierenberg maintained and even increased his influence through the George C. Marshall Institute. Cofounded in 1984. by him, Robert Jastrow and Frederick Seitz, this institute became a central platform for questioning climate science. His career shows how Cold War physicists, shaped by the atomic and military-industrial complex, came to use their authority not to deny environmental science outright but to amplify uncertainty and highlight economic costs in order to defer regulation.

Faithful to his ideology and methods, Bill Nierenberg would also become a key figure in the science–policy debates surrounding climate change when he was appointed chair of the Carbon Dioxide Assessment Committee (see the portrait of Thomas Schelling in chapter 4).

Source : Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2010).

Thierry Déau

Ranked 233rd richest professional in France in 2025 by Challenges1, with a fortune of €600 million, Thierry Déau is spearheading environmental derisking in France. He is close to Emmanuel Macron—notably, he provided significant funding for his first presidential campaign. And, he founded the Meridiam investment fund in 2005, which manages more than €23 billion in assets. By specializing in sustainable infrastructure investments, Meridiam prides itself on complying with a number of criteria defined by international organizations, such as the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment and the environmental, social, and governance standards of the European Investment Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and the International Finance Corporation.

Today, Meridiam manages 130 projects worldwide, ranging from a wind farm in Egypt to Terminal B at LaGuardia Airport in New York City to five hospitals in Turkey. On its website, the investment fund divides its assets into three categories: (1) “sustainable mobility”, which includes the construction of railways, tramways, and airports, (2) “innovative low-carbon solutions”, because Meridiam invests in renewable energy production, drinking water supply, and electric vehicle charging stations, (3) and finally, ironically, the misnamed “essential public services” (hospital beds, healthcare facilities, and nurseries).

Thierry Déau was one of the main instigators of derisking. After working for ten years at Egis Projects, a subsidiary of Caisse des Dépôts specializing in long-term project management, he decided to set up his own fund. His goal was to carry out activities similar to those of Egis, investing in infrastructure, but using private capital. He initially encountered resistance, as he told a journalist from Les Échos, “because the pursuit of short-term profitability is not compatible with public service activities”.2 His success came after the 2008 financial crisis. Thierry Déau attributes this to the fact that investors placed their trust in infrastructure after the failure of derivatives. Given Meridiam’s success, he was chosen as an expert by the European Commission and the European Investment Bank to implement the Juncker Plan, a derisking operation deployed by the European Union to revive the economy and improve European infrastructure. He helped found the Sustainable Development Investment Partnership, a derisking initiative co-founded by the OECD and the World Economic Forum in 2015.

What Thierry Déau strives for is to maintain an impeccable image for his business and himself. Involved in numerous philanthropic initiatives, he is one of the main patrons of the Paris Opera, among other things. Born in Fort-de-France into a modest family, he and his daughter founded the Archery Foundation, which supports students from working-class neighborhoods in their academic and personal development and finances their studies. In 2017, the West Guiana Power Plant project, financed by Meridiam, was awarded land by the National Forestry Office that had previously been used as a hunting forest by the indigenous population, without consulting them. After years of confrontation, Thierry Déau agreed to compensate the Kali'na village financially with an agreement to pay it €150,000, then €50,000 per year for the 25 years of operation of the site.3 Where his reputation has been more compromised, however, is in the Veolia-Suez merger case. Déau is among those suspected of influence peddling by the French National Financial Prosecutor's Office.

1 https://www.challenges.fr/classements/fortune/thierry-deau_26789

2 “Thierry Déau, le patron très engagé du fonds Meridiam”, Les Échos, Valérie de Senneville, 24 janvier 2023.

3 “En Guyane, le conflit autour d’une centrale électrique sur des terres amérindiennes se dénoue”, Le Monde, Laurent Marot, 31 octobre 2024.

Timelines

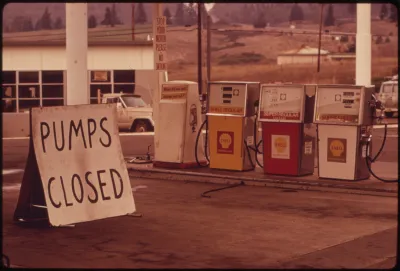

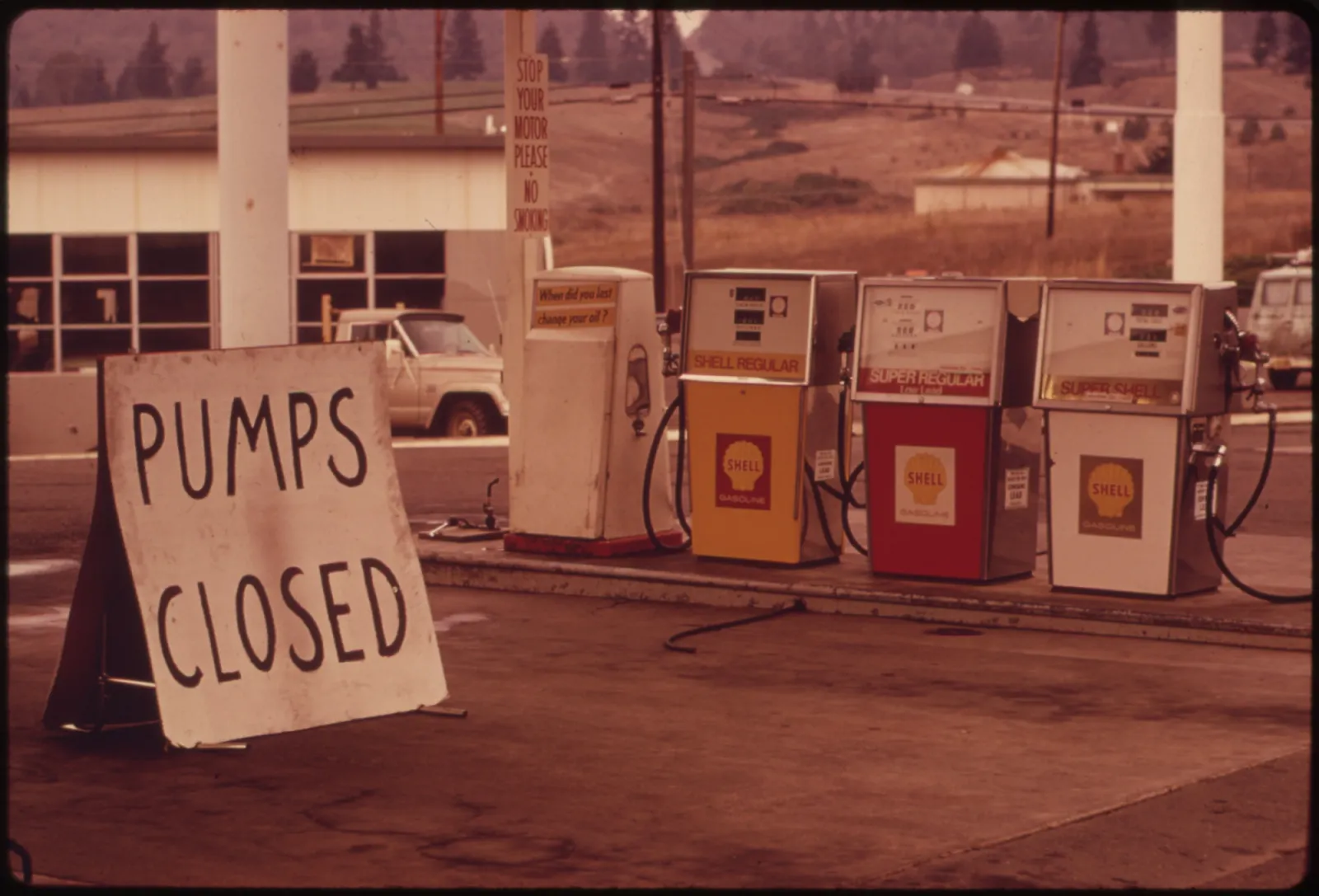

1973

OPEC and the First Wave of Resource Security. OPEC’s rise in the 1970s marked a turning point in Global South sovereignty over resources, challenging Western control by nationalizing oil industries. The 1973 oil shock, Chile’s 1971 copper nationalization, and rising fears of resource scarcity spurred U.S. policies like Nixon’s “Project Independence” and Carter’s energy security push. These revived WWII-era stockpiling strategies, including lithium. Today’s calls for a “Lithium OPEC” echo this earlier scramble to control extractive frontiers central to global capitalism.

2008

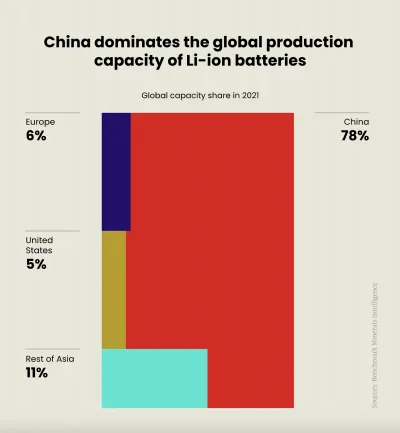

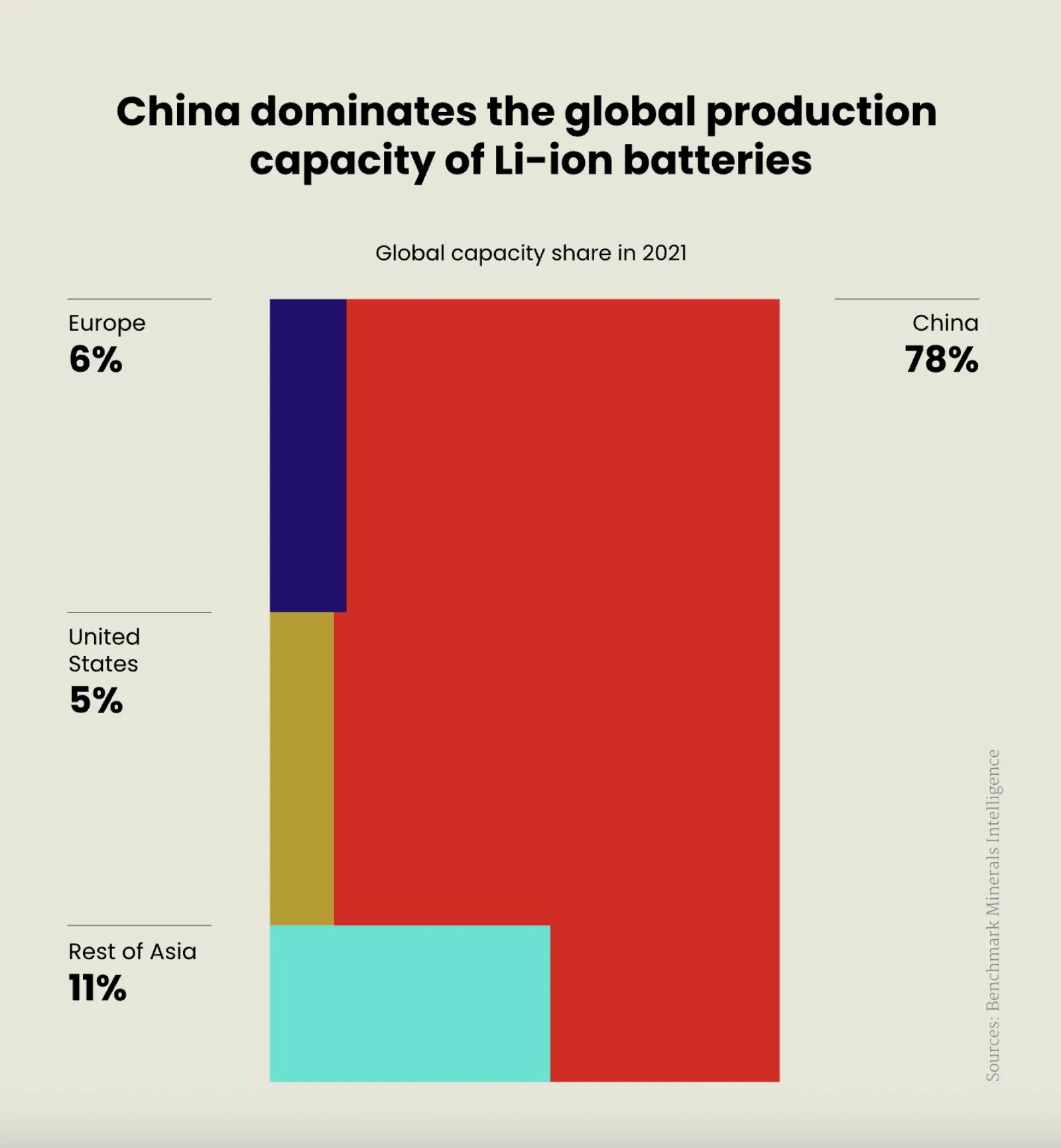

The Commodity Boom. The 2008 commodity boom, driven by China’s industrial rise, exposed Global North anxieties over resource dependence amid the financial crisis. While the U.S. reeled from economic collapse and movements like Occupy rose, resource-exporting nations thrived. Rare earth elements—vital for green tech—became a strategic concern as China gained control over 70% of supply. These materials, though not rare geologically, pose severe environmental and health risks in China, where lax regulation has led to toxic pollution and rising cancer rates in mining regions.

2018

Resource Security under Trump’s First Mandate. In 2018, the Trump administration expanded the definition of “critical minerals,” easing regulations to boost domestic extraction, notably of lithium. This shift, rooted in economic nationalism, linked mineral policy to national security and industrial revival. Executive Orders and bipartisan bills like Murkowski’s “American Mineral Act” framed reliance on Chinese imports as a threat. Ethical concerns over foreign extraction—raised even by officials like Francis Fannon, then Assistant Secretary of the Bureau of Energy Resources at the State Department—bolstered calls to reshore supply chains or source from trusted allies to safeguard the clean energy transition.

2021-2024

Biden’s Industrial Push for Green Dominance. The Biden administration expanded Trump-era mineral policies, tying resource security to the energy transition. A 2021 supply chain review led to a vertically integrated lithium strategy, invoking the Defense Production Act and funding mining, R&D, and recycling. The 2021 Infrastructure Act and 2022 IRA and CHIPS Acts provided billions in incentives while imposing strict sourcing rules to limit Chinese inputs. By 2024, Biden raised tariffs sharply on Chinese EVs, batteries, and minerals, framing green tech dominance as both economic and geopolitical strategy—blurring the line between climate action and protectionism.

2025

Trump 2.0. Since returning to office in 2025, Trump launched an aggressive critical minerals agenda. Executive Orders 14241 and 14272 invoked the Defense Production Act, expedited permits, and investigated import risks. Another order promoted offshore seabed mining for cobalt and rare earths. In May, 10 new mining projects were fast-tracked under the FAST-41 program. These moves aim to boost U.S. resource autonomy and reduce dependence on China, while securing dominance in tech-critical minerals—paradoxically paired with a broader rollback of renewable energy investments.

2015

“From Billions to Trillions”. Accessing private capital to finance infrastructure and public service projects became a solution proposed by international institutions, in a context where austerity policies led them to consider public funding as scarce. In July, the World Bank published “From Billions to Trillions”, and in September, United Nations member states adopted the Sustainable Development Goals. The “From Billions to Trillions” agenda is an initiative of the multilateral development banks (the African Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the European Investment Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank Group, and the World Bank), as well as the International Monetary Fund. It aims to establish the derisking operations necessary to finance the projects contained in the Sustainable Development Goals: leverage through their funds, policy and regulatory advice to help countries attract private capital funds to finance sustainable development. In the European Union, member countries adopted the Investment Plan for Europe. Also known as the “Juncker Plan,” it aimed to make up for lost investment and increase Europe’s competitiveness by using EU and European Investment Bank funds to leverage public and private financing.

2017

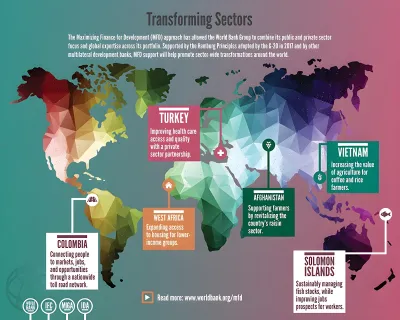

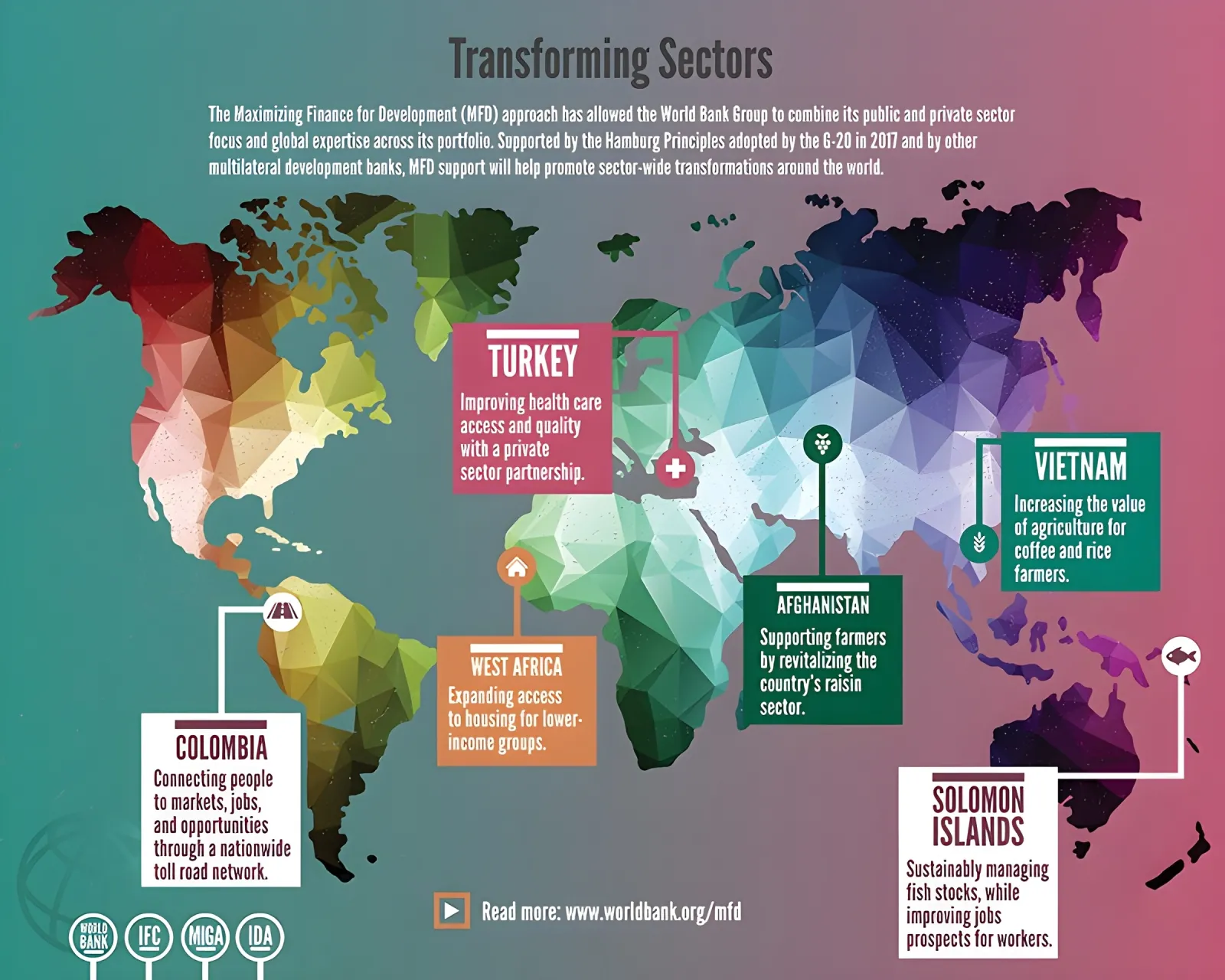

"Maximizing Finance for Development". The World Bank’s “Maximizing Finance for Development” aims to promote the use of private capital to finance development projects that seek to end extreme poverty while meeting sustainable development goals. It represents an intensification and systematization of “From Billions to Trillions”, following on from the Hamburg Principles adopted by the G20 in 2017. The three main priorities of the agenda are: strengthening investment capacity and adapting regulatory frameworks at the national and supranational levels; increasing private sector involvement and prioritizing commercial sources of financing; increasing the catalytic role of multilateral development banks.

2020

The European taxonomy for sustainable activities. The European taxonomy for sustainable activities was adopted in July. It defines the various activities carried out by financial and non-financial companies that could be classified as “green.” This form of regulatory derisking encourages companies to adapt their activities by awarding them “green labels”, without penalizing polluting investments. The green taxonomy acts as a nudge to support sustainable investments in sectors where the state is deemed unable to provide all the necessary financing.

2021-2027

The InvestEU program. In the European Union, the InvestEU program replaced the European Fund for Strategic Investments set up by the Juncker Plan to finance infrastructure projects through derisking. Its objective has been to support the EU’s competitiveness through investments in sustainable, innovative, social infrastructure (education, housing, healthcare, cultural activities, integration of vulnerable people) or small and medium-sized enterprises. For example, the European Green Deal, adopted by the European Parliament in 2020, has benefited from public funding but also largely from private funding mobilized by InvestEU—whose climate objectives will represent at least 30% of the financial envelope.

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter

Because resisting the world's rightward drift starts with taking the measure of it