Left Resistances

Worn down by the unraveling of the Keynesian social compromise and taken aback by the collapse of the Soviet empire, the Left was not at its best - electorally or intellectually – in the early years of the post-Cold War era. Adding to the morass, social justice advocates had to deal with a Zeitgeist full of neoconservative pronouncements about the demise of collectivism and neoliberal celebrations of globalization.

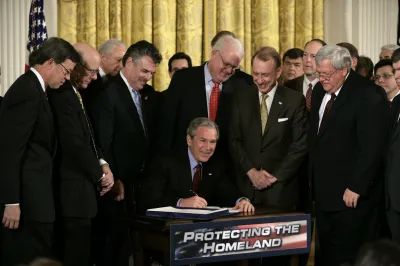

Gradually, however, the survivors of the “End of History” took advantage of their exile from the mainstream and adjusted their own lenses. Much of the left learned to expose the fallacies of the “war on terror”, to debunk the efficient market hypothesis, and to counter the arguments of fossil fuel lobbies. The disastrous Bush wars, the stock market crash, and the IPCC’s increasingly ominous alarms made left critiques impossible to dismiss. Politically, however, progressives hardly reaped the rewards of their adversaries’ discredit.

Two decades later, the task confronting Left activists seems even more daunting. While still reeling from their failure to take advantage of the legitimacy crises of neoconservatism and neoliberalism, they now must reflect on these missed opportunities in light of the new challenges posed by the world’s far-right drift. Trained to question assumptions about the elective affinities of capitalism and democracy, the contribution of free trade to global prosperity, and the virtues of enticing private investors to lead the energy transition, their skills are of little use against foes whose policymaking is predicated on executive privilege, mercantilist calculations, and unapologetic extractivism.

Rather than reckoning with a rapidly deteriorating political environment, it may be tempting to pretend that nothing has really changed. Hence the propensity, in some quarters of the Left, to indulge in the comfort of waging yesterday’s wars. The stakes are arguably too high, however, to keep looking at uncharted perils through familiar but increasingly obsolete prisms. Indeed, neither the anti-imperialist indictment nor the anti-totalitarian endorsement of the defunct international liberal order can shed much light on our dystopian world.

From Washington to Beijing, via Moscow, Delhi, Ankara and Jerusalem, the strongmen in charge of the brutal new order seem bound by a kind of gentlemen’s agreement: while vying for access to energy sources and treating their own citizens without much regard for human rights and civil liberties, they tend to respect each other’s license to govern their regional zones of influence as they please. This explains why, despite their cynical and predatory ways, they tend to fancy themselves as peacemakers.

To offer a measure of hope in this context, the Left must take stock of what it is up against and reorganize accordingly. Assessing its progress thus involves tracking: (1) the sites where resistances are emerging – i.e., where social movements are taking root but also the issues around which they are mobilizing; (2) the strategies that activists invent or rediscover to undermine overtly undemocratic regimes; and (3) the new solidarities rising among peoples and communities who share the misfortune of being targeted by one of the world’s major bullies.

How Italy Lost its Antifascist Compass

Interview conducted on 13 October 2025

“The movements we're dealing with today in Italy, the cradle of fascism, never disappeared. There is no point in talking about the return of fascism; it has always been there.”

Year Zero in The Middle East

Interview conducted on 30 August 2025

"This is a significant moment for the region. But will it also be a defining moment for the world? How can we build alliances around this so that it does not remain the destructive phenomenon we are witnessing? I think that is the big question."

THE ARGENTINIAN LABORATORY

Interview conducted on 01 April 2025

"Milei presented himself as the final outcome of the representational crisis of the system."

POSTDEMOCRACY IN AMERICA

Interview conducted on 23 February 2025

“Race has always been used, in American politics, as a battering ram against every public good, any redistributive impulse, any idea of collective freedom or social freedom. If you go in there with race, saying that what you’re doing is protecting white people from black people, then you end up protecting capitalists from social provision.”

GENOCIDAL INTENT

Interview conducted on 26 January 2025

"The genocide requires the intent to destroy people in whole or in part, or any protected group, in whole or in part. And the way to understand it is not really to just look at the evidence, but at the relation between evidence. So, in fact, it's become a meta-process. It's evidence about evidence."

Portraits

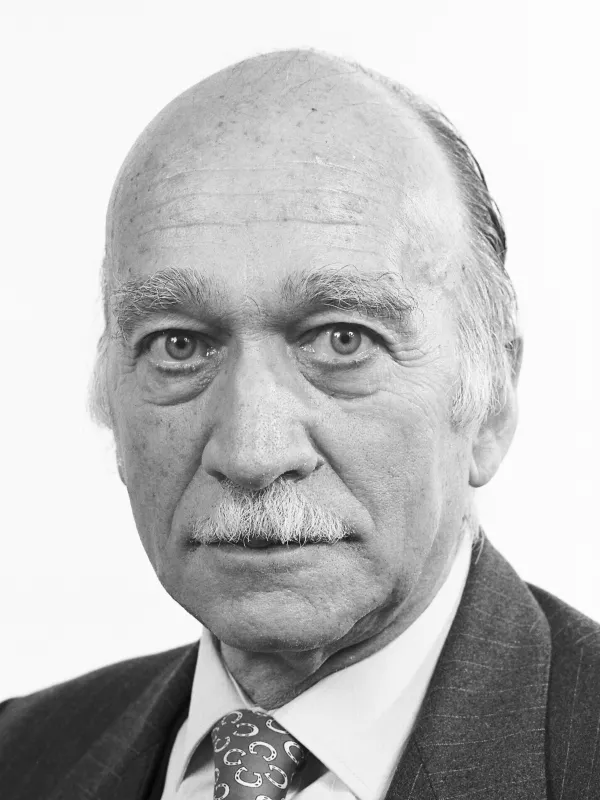

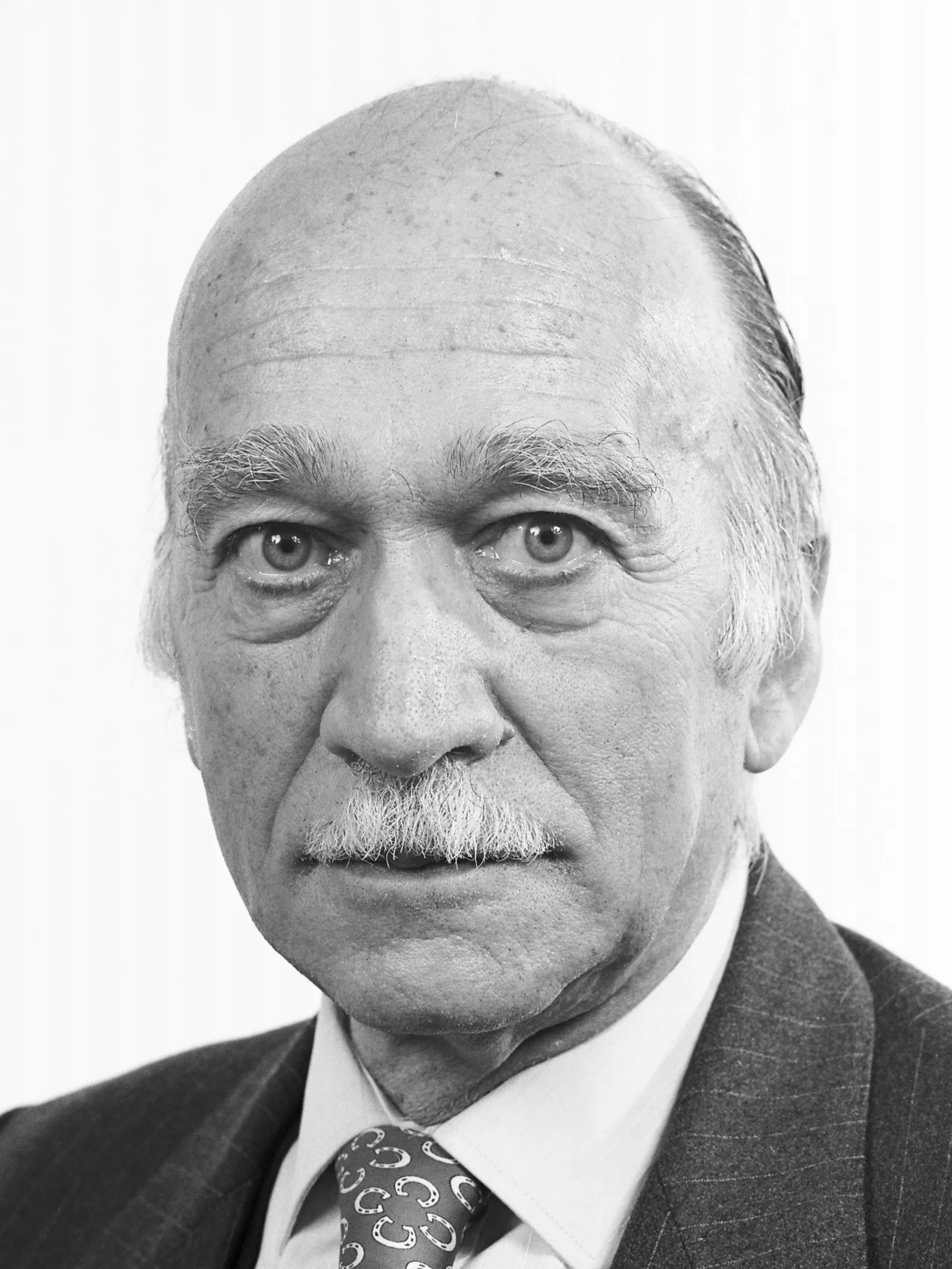

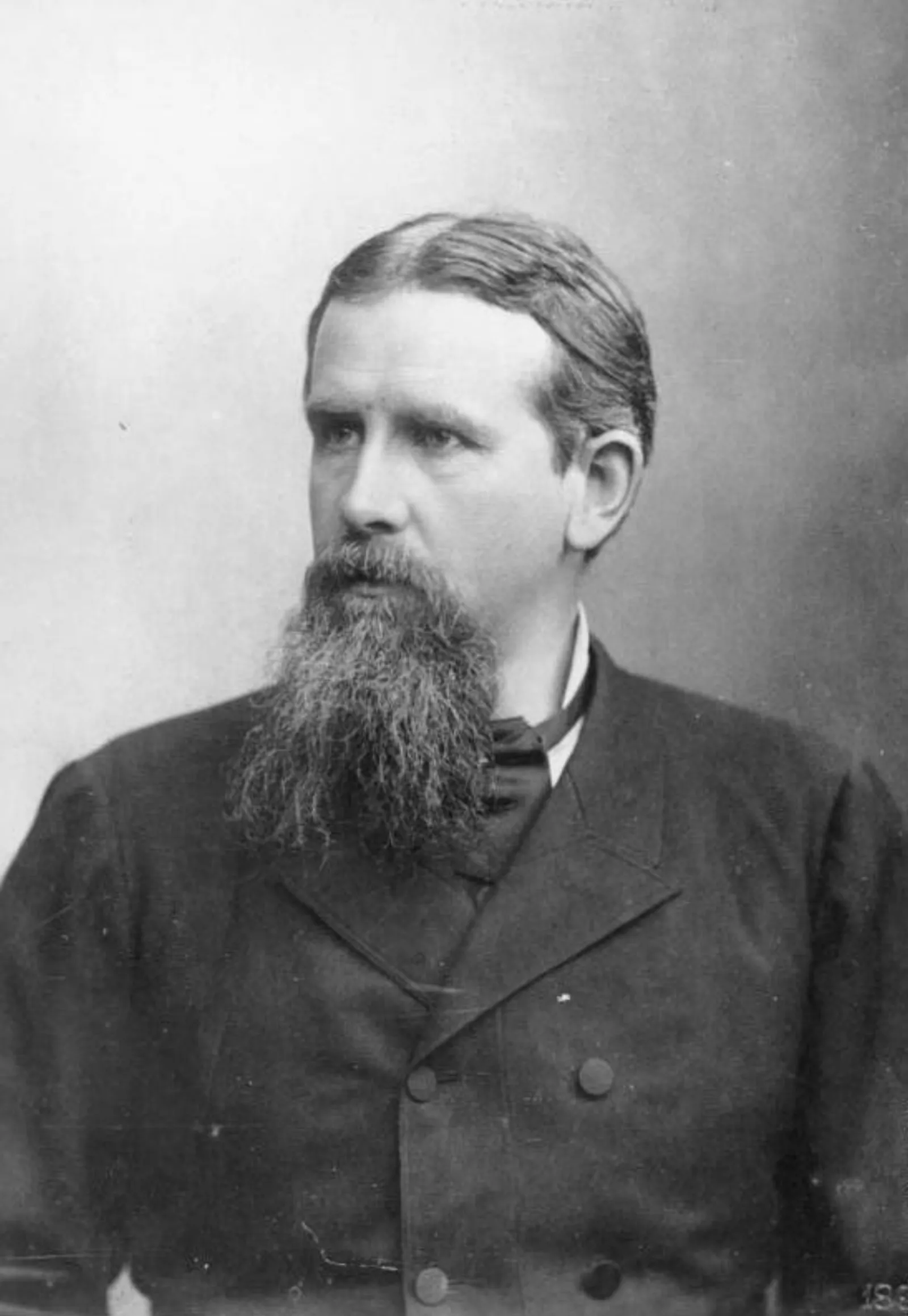

Giorgio Almirante

In 1946, when supporters and associates of Benito Mussolini founded the neofascist party Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI), they chose a tricolor flame as an emblem. While the most significant symbols of fascism had, until then, been the fasces or the imperial eagle, Giorgio Almirante, one of the co-founders who would become MSI’s long-time president, saw the flame as a powerful image: Mussolini’s spirit escaping from his coffin. He succeeded in imposing the symbol to galvanize his troops and engrave in their minds the idea that fascism should remain “the ultimate goal” (‘il traguardo’) he had helped to launch.

During the war, Almirante had been a theorist of racism and a propagandist of anti-Semitic “racial laws”. Throughout his entire parliamentary career, and until his death in 1988, he shamelessly asserted that his Movimento Sociale Italiano had been conceived as a party of "fascists within a democracy”. His ambition was simply to adapt an old cause to the realities of the new era. Responding in 1982 to an exhortation by the founder of the Italian Radical Party, Marco Pannella, to clarify his party’s relationship to the fascist legacy, Almirante stated: “[The MSI] represents fascism as freedom, not as a regime—that is, as a movement, as a social tradition, as a synthesis of values”.

Under Almirante, the MSI was fiercely anticommunist and dedicated to an alliance with the monarchist right, which was unwilling to compromise with the “Constitutional Arc”. The party remained implicated in a range of conspiracy to overthrow the State and instigated terrorist acts until the 1980s. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Giorgio Almirante also activated his international neo-fascist networks. In particular, he was behind the creation of the National Front in France in 1972, advising members of the far-right Ordre Nouveau (New Order) movement on how to establish a party of “fascism with a smiling face”.

Initially a film critic and voice actor, Almirante later became involved in political journalism. He soon became editor of the newspaper Difesa della Razza (“Defense of the Race”) and in 1938 signed the Manifesto della razza (“Manifesto on Race”), which set out the racist measures implemented by Mussolini. The scribe then rose through the ranks in Sardinia and Libya, where he took part in the North African Campaign. When the Italian Social Republic was established in 1943, a puppet state and vassal of the Third Reich, Almirante followed the Duce to Salò. This earned him the position of chief of staff of the “Ministry of Popular Culture” headed by Fernando Mezzasoma during the last two years of the war. It was then that he demanded that his followers prepare for a “physical confrontation” with the partisans and that he himself became actively involved in this counter-resistance, on the side of the Lepontine Alps and in Tuscany.

When the MSI was founded in 1946, Almirante established the party headquarters at Via della Scrofa 39, which would later become a legendary address for the Italian right, just like Via delle Botteghe Oscure for the communists, Piazza del Gesù for the Christian Democrats, and Via del Corso for the socialists. In addition to the management office, it also housed the editorial office of the newspaper Il Secolo, a sort of central organ for the neo-fascists. Silvio Berlusconi with Forza Italia and then Giorgia Meloni and her Fratelli d’Italia later took up residence there. A leading figure of the Italian far right during the First Republic, Almirante has enjoyed a posthumous revival since the turn of the century as an idol of transalpine neo-fascists. Under Berlusconi’s leadership, when the restoration of fascist heritage and monuments began in Italy, some municipalities even went so far as to rename streets in honor of Giorgio Almirante and other prominent figures of historical fascism. More recently, Almirante was also celebrated by Meloni, who claimed in her autobiography Io sono Giorgia (“I am Giorgia”), published in 2021, to have “taken over from Giorgio Almirante,” her long-time political idol.

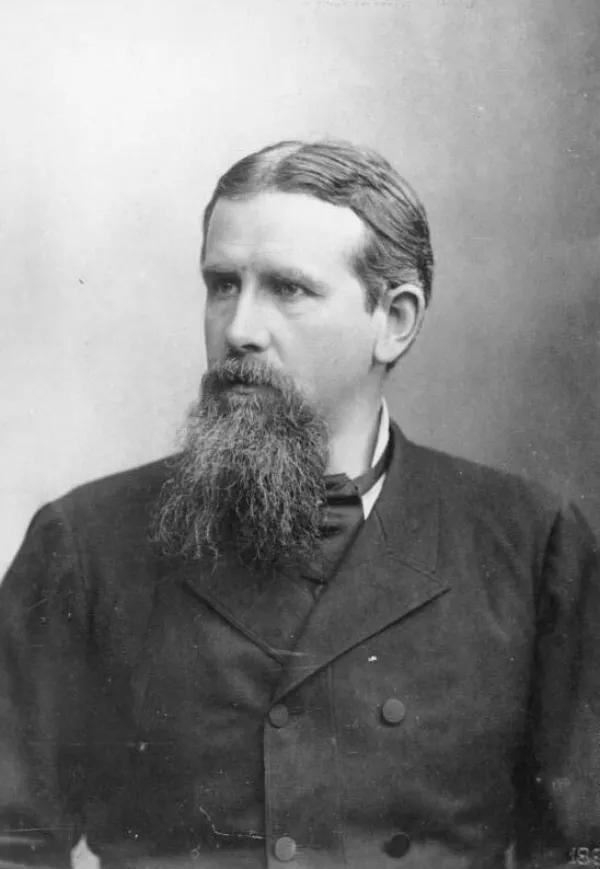

Raphaël Lemkin

Raphael Lemkin (1900-1959) was a Jewish Polish lawyer trained at the Lwów law school (now Lviv, Ukraine), who escaped to Sweden and eventually to the United States after the occupation of Poland by the Nazis. He coined the term genocide and was pivotal in clarifying its multifaceted legal definition, with which state-led mass murder could be criminalized.

In the early 1920s, Lemkin was already scrutinizing the systematic elimination of the Armenian people that had accompanied the fall of the Ottoman Empire. Then, two decades later, he became one of the first legal scholars who not only perceived the specific nature of the crimes committed against the European Jews, but who also extended the notion of genocide to instances of settler colonial violence, such as the treatment received by some Slavic groups during the Second World War.

As outlined in his major research on Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, genocide “is intended (…) to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves. The objectives of such a plan would be disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups, and the destruction of the personal security, liberty, health, dignity, and even the lives of the individuals belonging to such groups. Genocide is directed against the national group as an entity, and the actions involved are directed against individuals, not in their individual capacity, but as members of the national group1.”

1 Raphael LEMKIN, Axis rule in occupied Europe : laws of occupation, analysis of government, proposals for redress, Washington, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Division of International Law, 1944, p. 79.

Francesca Albanese

Francesca Albanese is an Italian international lawyer and academic affiliated to Georgetown University and the organization Arab Renaissance for Democracy and Development. She has served as the UN Special Rapporteur on the Palestinian Territories since 2022, and her three year mandate was renewed in 2025.

Since her first report, calling for action to end the Israeli settler-colonial occupation and apartheid regime, including through boycotts and sanctions, Albanese has personally been the target of recurrent smear campaigns, along with delegitimation attempts against the United Nations. Her latest report presented in March 2024 at the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva expounded detailed evidence for Israel’s intentional enactment of at least three “genocidal acts” against the Palestinians.

She is currently preparing a report on Israel's experimentation with new military technology, such as remote-controlled quadcopters, autonomous lethal weapons and killer robots.

Patrick Buchanan

According to his apologists, Patrick Buchanan is neither a racist nor an antisemite. He merely says racist and antisemitic things. As a former speechwriter and pundit, Buchanan has certainly resorted to words in order to make a living. Yet it would be unfair to suggest that, instead of being a true bigot, Buchanan was only playing one on TV.

Regarding race relations in the US, Richard Nixon, who employed him at the time, summarized his press secretary’s position as “segregation forever”. As for Jews, Buchanan’s statement on Treblinka not being an extermination camp squarely falls under the rubric of Holocaust denial – not to mention his kind words about Hitler. As fellow conservative commentator Charles Krauthammer once remarked, “(t)he interesting thing (about Buchanan) is how he can say these things and still be considered a national figure.”

One should add that even his most fervent advocates never tried to argue that Buchanan’s homophobic, xenophobic and sexist rants did not reflect his true self. At best, they might have claimed that the views he proffered on the AIDS epidemic – nature’s revenge on homosexual practices – immigration – an existential threat – and the role of women – “building the nest”, like “Momma Bird” – were less his own than those of the God he worships.

Born in Washington in 1938, Patrick Buchanan was raised as a traditionalist Catholic. His great-grandfather fought under General Robert E. Lee, and he remains a proud member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. A streetfighter and a bully in his youth – his family’s Jewish neighbors were his favorite target – “Pat” eventually matured, attending the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University and starting his journalistic career at the Saint-Louis Globe-Democrat.

In 1966, Buchanan was hired by Richard Nixon’s campaign team to write the speeches meant for the candidate’s conservative base. Among other accomplishments, he coined the phrase “Silent Majority”. After the election, he worked as White House assistant and speechwriter, kept his job during Nixon’s unfinished second term and remained faithful to his boss until the bitter end – he even urged the President to burn the Watergate tapes in order to stay in power.

When Gerald Ford took office, the new administration briefly considered making Buchanan the US ambassador to apartheid South Africa. However, because of his segregationist inclinations and his excessive enthusiasm about getting the job, the State Department eventually rescinded the offer. Temporarily retired from politics, Buchanan embarked on a long and successful career as a news commentator, first at NBC radio then on cable TV – where he successively joined NBC’s The McLaughlin Group and CNN’s Crossfire and The Capital Gang. In these popular shows, Buchanan was typically cast as the conservative voice pitted against a liberal counterpart.

The renowned pundit came back to the White House in 1985 as Ronald Reagan’s Communications Director. During his two-year tenure, Buchanan was instrumental in the organization of the President’s visit to the German cemetery of Bitburg, where 48 Waffen SS members were buried. While busy defending the Administration’s decision – in the face of widespread outrage – the Communications Director used his spare time fighting the deportation of suspected Nazi war criminals to countries of the Eastern bloc. For Buchanan, honoring the Wehrmacht’s sacrifice and frustrating the plans of “revenge-obsessed Nazi hunters” were two sides of the same mission – one that his great-grandfather would have surely condoned.

After leaving the Reagan administration and returning to punditry, Buchanan felt freer to embrace his favorite causes. In 1989, for instance, he paid yet another tribute to his Confederate ancestor by writing a column about the so-called Central Park Five case: in his article, he called for the public hanging of at least one of the Black teenagers falsely accused of having raped a white jogger.

At about the same time, Pat started encouraging his sister Bay, who had also worked for the Reagan administration, to pursue her “Buchanan for President” initiative. The siblings’ platform was two-pronged.

On the domestic front, Buchanan lambasted the open border policy promoted by the globalist wing of the Republican party – or at least by the contributors to the editorial pages of the Wall Street Journal: mass immigration from non-European countries, he warned, would fatally imperil the cultural and moral fabric of the United States.

With respect to foreign affairs, the former speechwriter argued that the closing of the Cold War should also mark the end of US military involvement throughout the world. Hence his staunch opposition to the Gulf War in 1990, which prompted his decision to run against George H.W. Bush two years later.

In the Republican primaries of 1992, Buchanan ran as the paleoconservative candidate: he challenged the incumbent President, whom he accused of harboring both a liberal and an imperialist agenda. Bush, Buchanan complained, had not only reneged on his “no new taxes” pledge: even more importantly, his administration had failed to curb immigration, to hinder women’s access to abortion and to suppress gay rights. Meanwhile, he added, the Jewish lobby and its neoconservative proxies were allowed to dictate the terms of America’s foreign policy.

Buchanan failed to win the nomination but still received almost a quarter of the votes. He also delivered his famous “culture war” speech at the Republican convention, where he claimed that America was in the grips of a decisive struggle for its own soul: the choice was between remaining “God’s country” or descending further down the liberal and multicultural path of moral decline. Though some commentators blamed the Republican defeat in the presidential election on the chilling effect of Buchanan’s oratory, the paleoconservative tribune persisted. After returning to Crossfire, he created a foundation called the American Cause to prepare himself for his next bid. He ran against Bob Dole, in the 1996 primaries, and was defeated once again.

After his second attempt, Buchanan began to despair of the Republican party, which he left in 1999. The following year, he ran as the candidate of the Reform party. While his campaign failed miserably, he inadvertently played a decisive role in George W. Bush’s controversial victory. In Palm Beach, Florida, about 2,000 ballots meant for Al Gore, the Democratic candidate, were mistakenly credited to him. Because the conservative Supreme Court rejected Gore’s request for a recount, his opponent was declared the winner in Florida, which gave him enough delegates to become President.

After 2000, Buchanan gave up on presidential politics and left CNN for MSNBC, where he was one of the few pundits who opposed Bush’s decision to invade Iraq. He also became even more overt in the defense of his other pet causes: one of his columns stated that the UK should not have declared war on Nazi Germany and his book entitled Suicide of a Superpower explicitly lamented the waning of white supremacy in America. Yet it was not until 2011 that MSNBC decided to end his contract.

Five years later, Donald Trump won the presidential election on a platform that largely echoed Buchanan’s. The latter had endorsed the MAGA candidate of course, though Trump’s success must have been bittersweet for the culture war veteran – who continued to write articles, mostly for Peter Brimelow’s white supremacist site VDARE, until 2023.

Similarities between their outlooks notwithstanding, the extent of Buchanan’s actual influence on the 47th President is open to debate. What his charmed professional life reveals, however, is the fact that long before Trump, Washington’s mainstream media and political establishment would already welcome an unapologetic segregationist and Hitler sympathizer as one of their own.

Friedrich Ratzel

Friedrich Ratzel (1844–1904) was a German geographer and zoologist who had a major influence on German geopolitical thought at the turn of the 20th century. Intoxicated by his social Darwinism, he developed dubious biologistic concepts to describe the differential development of states and their spatial expansion.

His ideas are considered a decisive impetus for the “Lebensraum” ideology of National Socialism, the postulate that a strong and self-sufficient nation-state requires ample space and resources to feed its population and support its industry, which in turn legitimizes plundering neighboring territories.

Eighty years after Hitler’s defeat, Ratzel’s infamous concept seems to be enjoying a rebirth of sorts, at least among the advocates of a “Russian World” that would absorb Ukraine, of a “Land of Israel” that would annex the West bank and Gaza, and even of a “Greater America” that would range from Greenland to the Panama Canal and even include Canada

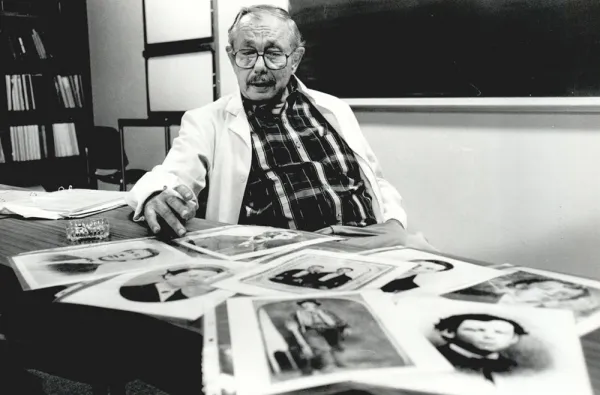

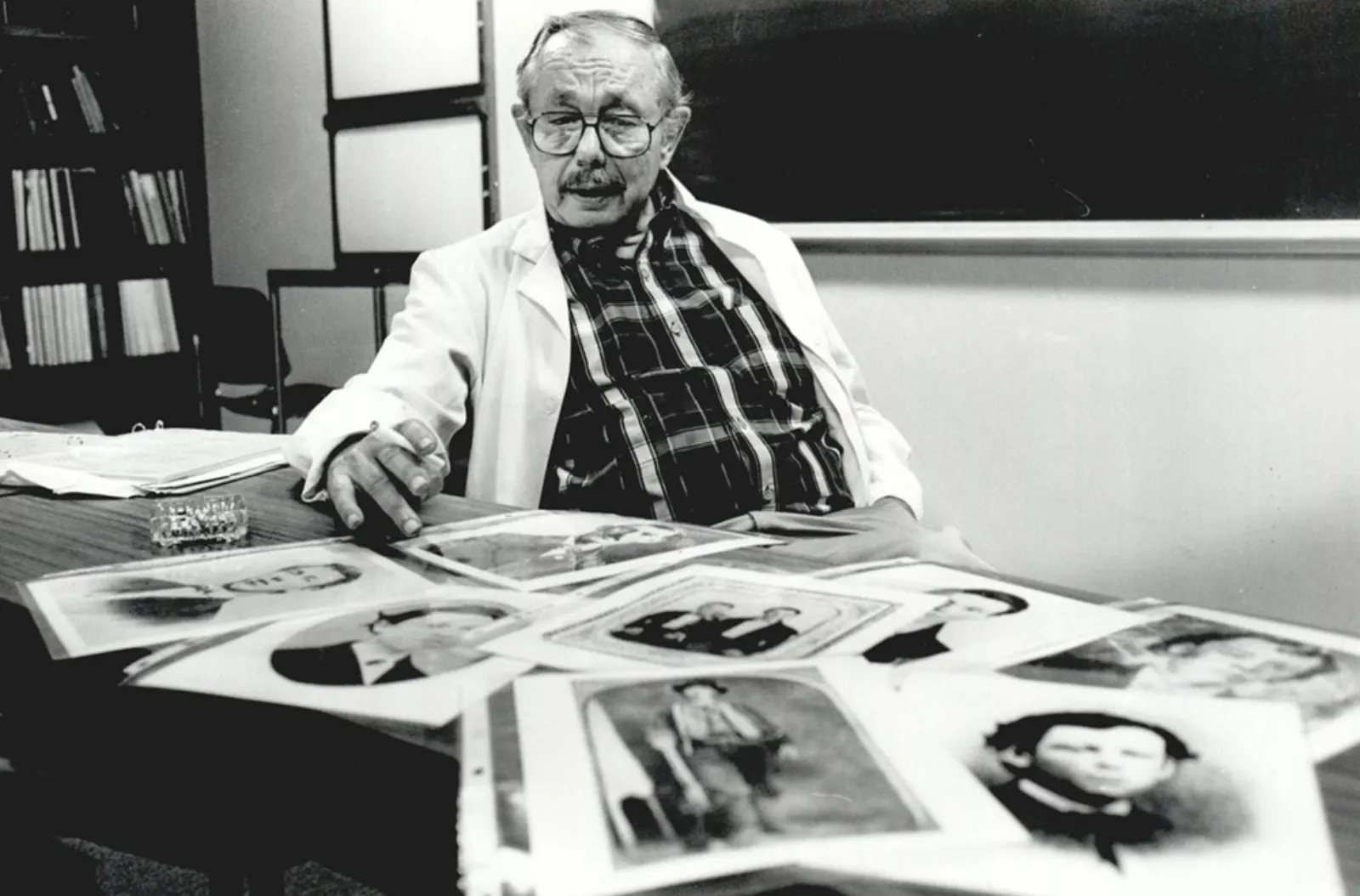

Clyde Snow

“Being dead is not a problem, dying is.” Clyde Snow often repeated these words, as the bodies he autopsied lay at the bottom of mass graves. An expert listener to such silent witnesses, the American medical examiner and anthropologist spent years reconstructing the story of their final hours by documenting the traces of abuse, torture, beatings, or execution engraved in their bones. Snow’s work was ultimately aimed at identifying these bodies and restoring their dignity.

Forensic anthropology began in 1865, when Clara Barton was commissioned by Abraham Lincoln to identify unknown soldiers who had fallen on the battlefield during the Civil War. In 1984, the discipline took on a new dimension. Clyde Snow's expertise was then called upon in Argentina, where it was no longer just a matter of restoring the identity of human remains, but of proving, through anthropometric study, the “dirty war” waged from 1976 to 1983 by the military dictatorship of General Videla.

Clyde Snow enthusiastically accepted the mission, seeing it as an important new application of forensic anthropology: documenting human rights violations. He thus headed to the mass graves where death squads had piled up some of the 30,000 desaparecidos. Bullet wounds and perimortem fractures were among the evidence that the anthropologist then presented at the trial of the Argentine generals responsible for these massacres, leading to the conviction of five of them.

In Croatia, he discovered the remains of 200 patients and hospital staff executed by soldiers. In El Salvador, he found the skeletons of 136 children and infants who had been shot by army squads. In the Philippines, Bolivia, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Rwanda, Chile... all over the world, Clyde Snow has excavated bodies from mass graves and provided evidence of atrocities committed by governments, dictatorial regimes and generals, so that those responsible can be brought to justice. As one of the main witnesses at Saddam Hussein’s trial for genocide against the Kurdish ethnic group in 2007, the anthropologist stood for four hours presenting detailed forensic evidence of the use of sarin gas and summary executions.

A member of the United Nations Human Rights Commission, Clyde Snow became the father of a movement that put forensic anthropology at the service of human rights campaigns against genocide, massacres, and war crimes. In more than 20 countries, he scientifically and psychologically trained experts in excavation techniques designed to preserve evidence, identify human remains in conflict situations, and reconstruct the conditions of their death.

Bones never lie and never forget, Clyde Snow used to say. “Their testimony is silent, but very eloquent.”

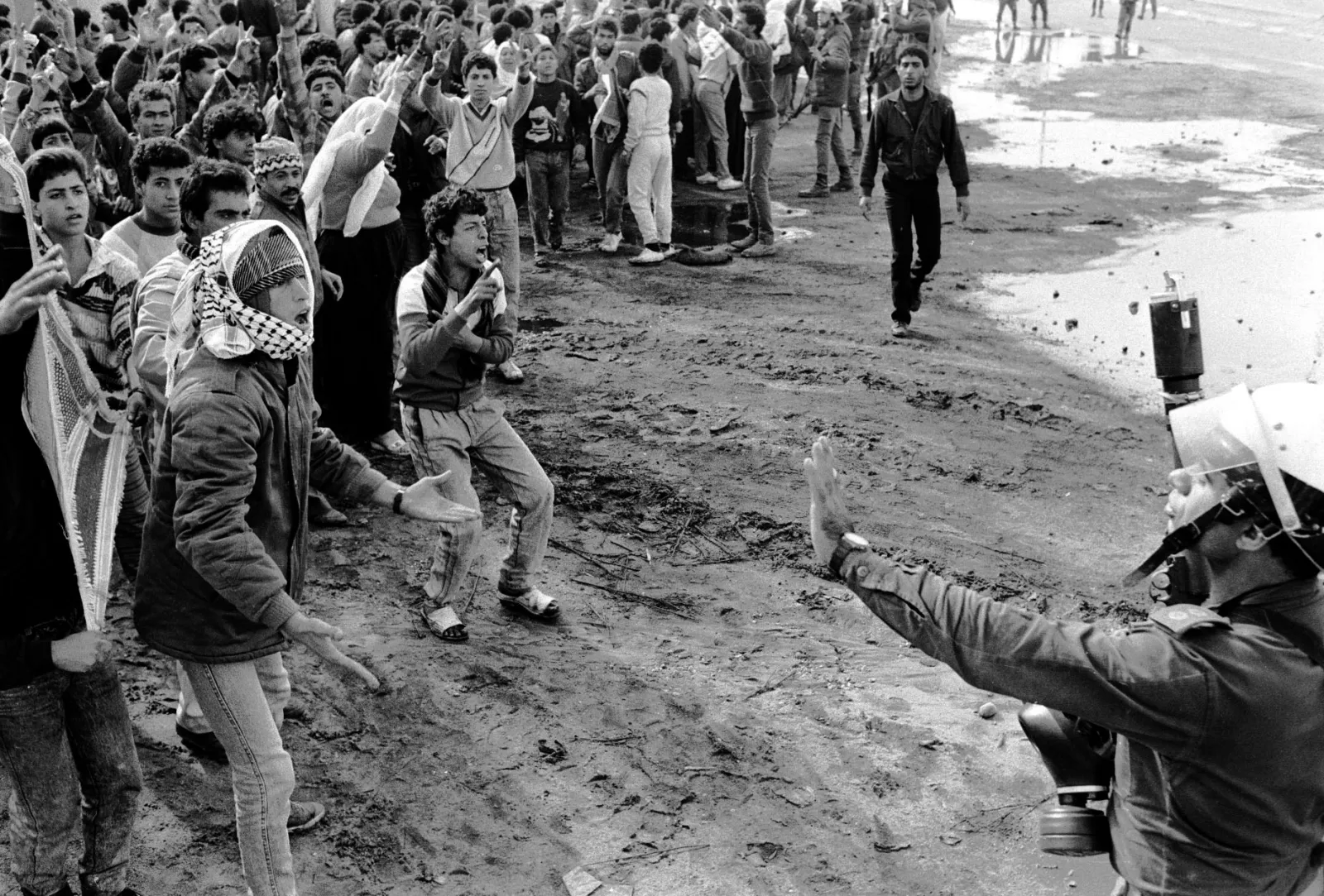

Ghassan Abu-Sittah

Ghassan Abu Sittah is a British-Palestinian surgeon, who regularly intervenes in conflict and crisis situations, including in Palestine where he first came as a medical student at the time of the First Intifada. During the Nakba, his father’s family were expelled from their land and became refugees in the Gaza Strip, before moving to Kuwait and later to the United Kingdom.

Amidst the urgency of October 2023, Abu Sittah once again returned to Gaza to volunteer with Doctors Without Borders, performing numerous amputations and other procedures at al-Shifa, al-Awda, and al-Ahli hospitals. The latter was targeted by a first Israeli attack on October 17 of that year, killing and injuring hundreds of civilians, as Abu Sittah was conducting an operation inside the hospital.

With his first-hand experience of devastating injuries, including burns caused by white phosphorus, he has supported multiple investigations into war crimes. There have been multiple attempts to silence Abu Sittah and to suspend his medical license. In April 2024, Germany banned him from obtaining a visa for one year in the entirety of the Schengen area.

Palmiro Togliatti

Palmiro Togliatti occupies a singular place in the history of the Italian left. As the founder of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) and an outspoken opponent of fascism, he was also a man of compromise who gave up on his revolutionary hopes after the resistance war.

A friend of Gramsci, he joined the Italian Communist Party (PCI) in 1914 and campaigned on its far left for its transformation into a revolutionary party. Faced with the PSI’s reformism during the factory occupations of the biennio rosso, he broke away and participated in the founding of the PCI at the Livorno Congress. In the 1920s, Togliatti took on increasing responsibilities within the party and distinguished himself as a privileged intermediary between Moscow and Europe. After Gramsci’s arrest, who had become secretary general of the PCI, Togliatti also faced repression. Fortunately, he was in Moscow when the main Communist leaders were arrested. Appointed to the party leadership, he worked from abroad to organize the PCI clandestinely and develop a strategy to defeat fascism, which gradually took the form of the “popular front policy”. His analysis of fascism as a “reactionary mass regime” is recorded in the “Course on Adversaries” he gave in Moscow in the spring of 1935.

During the war, the anti-fascist struggle was closely tied to the fight against capitalism (see text on the Action Party in chapter 2). It was in this sense that the various resistance parties (the PCI, PSI, and Partito d'Azione) agreed on a principle of non-compromise with the monarchy. The anti-fascists demanded the king’s abdication and Marshal Badoglio’s resignation, both of whom were accomplices of Mussolini’s regime, in order to prevent the popular resistance effort from being hijacked by the monarchist elite.

Yet, when he returned to Italy in March 1944, Togliatti broke with the anti-fascist line and called for the formation of a government with the king and Badoglio. This break, known as the “Svolta di Salerno”, can be explained by directives he received from Stalin on the night of March 3-4, 1944. These directives prioritized the geopolitical interests of the USSR, (i.e., the consolidation of Italy’s power vis-à-vis Germany and England), rather than the interests of the Italian working class. Where anti-fascism could have led to the construction of a new political order, the Salerno turning point neutralized its aspirations and replaced it with diplomatic anti-fascism, under the leadership of the Communist Party.

After Italy’s Liberation, Togliatti found himself at the head of the largest communist party in the West, and seemed determined to do everything in his power to integrate it into liberal democracy. The amnesty he signed on June 22, 1946, as Minister of Justice, was intended to promote Italian reconciliation after the civil war and stabilize the Republic’s institutions. In concrete terms, it absolved thousands of fascists of their war crimes and allowed them to remain in their positions in the administration, the army, and large companies. Although aggravated crimes were theoretically excluded from the amnesty, these exceptions were rarely applied by the Italian judiciary, 90% of whom were still from the fascist administration. On the other hand, partisans were prosecuted by the courts, which fueled deep resentment among former resistance fighters. While this gesture helps us understand how Italy’s transition from fascism to democracy took place, it also explains the survival of fascism in democracy. Indeed, the amnesty allowed for the rapid rebirth of legal political fascism, with the founding of the Italian Social Movement in 1946. By prioritizing institutional and state reconstruction, Togliatti and the PCI participated in a process of erasing the memory of fascist crimes, which has long benefited the Italian far right.

The trajectory traced by Togliatti, who remained at the forefront of the PCi until his death in 1964, demonstrates the ways in which anti-fascism was overtaken by heterogenous logics (Soviet, conservative, and liberal), and thus diverted from its initial goal.

Beppe Grillo

An accountant by training who later became a comedian and then a populist leader, Beppe Grillo is a key figure for understanding the transformations of Italy’s political landscape in the 2010s. He gained nationwide fame through his satirical stage shows and television appearances, where he filled stadiums and drew laughter by relentlessly castigating Italian politicians, whom he accused of widespread corruption. Critical of the operations of major industries, Grillo often relied on experts to grasp the technical dimensions of the issues he addressed, incorporating this detailed knowledge into his performances. When Telecom Italia was privatized, for instance, he purchased shares in the company in order to secure an invitation to its annual general meeting, where he publicly denounced the privatization in front of its investors.

Beppe Grillo’s career took a decisive turn in the early 2000s, following his meeting with Gianroberto Casaleggio. After encountering Casaleggio, a specialist in digital communications, at the end of one of his shows, Grillo was encouraged to create a website through which he could disseminate his views on current affairs and politics. Launched in 2004, Beppe Grillo’s blog quickly became a must-read platform in Italy. He used it to denounce politicians’ spending practices and the lack of generational renewal within the political class, which he described as a “gerontocracy.” The blog also served as a space to criticize the privatization of public services and the corruption that accompanied these processes. In 2007, drawing on his growing influence, Grillo called for the organization of a “Vaffanculo Day”, held on September 8. Thousands of people gathered across the Italian peninsula to collect signatures in support of a proposed bill titled Clean Parliament, an explicit reference to the Mani pulite investigations. The bill sought to bar individuals with criminal convictions from entering Parliament and to limit parliamentary careers to two consecutive terms. Although only 50,000 signatures were required, the Grillini collected more than 300,000.

In October 2009, Grillo founded the Movimento Cinque Stelle (Five Star Movement). Claiming to be “neither right nor left,” the party adopted a populist orientation, both in its methods and in the substance of its demands. Its five core themes echoed the topics developed on Grillo’s blog and were designed to appeal to a broad constituency by addressing issues that directly affected people’s material conditions while articulating a shared critique of governmental mismanagement: the return to public control of water services, a zero-waste policy, the expansion of sustainable public transport, a transition to renewable energy, and free access to Wi-Fi. Corruption remained a pervasive concern throughout the movement’s discourse, while free Internet access was framed as a means of circumventing the political propaganda disseminated through television.

Grillo and Casaleggio devised an organizational structure that they believed would guard against the corruption they denounced in other political parties. Their so-called “transparency strategy” stipulated that both party policies and electoral candidates would be selected through online voting. The movement was almost entirely digitized: it had no physical headquarters, and the Internet—still only partially embraced by its political rivals—served as the primary infrastructure for what they presented as a form of direct democracy. All of the movement’s statutes, press releases, and policy proposals were made publicly available online. Communication took place almost exclusively through social media. Viewing the press as hostile, the movement avoided making major announcements through newspapers and sharply limited its presence on television. The party also claimed to operate without a hierarchical structure. Candidates were expected to embody the moral integrity that the movement accused other politicians of lacking: elected representatives were required to have clean criminal records and to commit themselves to opposing public funding for political parties. Because Beppe Grillo had been convicted in 1980 of involuntary manslaughter following a car accident that resulted in three deaths, he was therefore ineligible to stand for election. Rather than weakening his authority within the movement, this restriction paradoxically reinforced his popularity, as it was interpreted by supporters as a guarantee of his sincerity. At the same time, Grillo retained the power to exclude activists who challenged him.

Despite this emphasis on direct democracy, criticism of the established order, and interest in environmental issues and certain public services, Beppe Grillo did not defend workers’ rights. A precursor to Javier Milei and Donald Trump, he mobilized his critique of the political system to attack specific aspects of the state, particularly social welfare. Echoing the anti-state rhetoric of Berlusconi’s right wing, he denounced “welfare dependency” and criticized the power of trade unions. The model of society he promoted was environmentally oriented but rested above all on individual responsibility. Through this combination, Beppe Grillo and the Five Star Movement succeeded in attracting voters from both the right and the left. The movement quickly achieved electoral success. In the February 2013 legislative elections, Grillo’s party upended the political landscape by winning 25.6% of the vote in the Chamber of Deputies and 23.8% in the Senate. It thus sent 109 deputies to the Chamber and 54 senators to the upper house. All were politically inexperienced, and their arrival initially disrupted established parliamentary routines. Enrico Letta, Prime Minister from 2013 to 2014, acknowledged that “it woke us up. And it is largely thanks to them that we chose new figures to lead the assemblies: a former anti-Mafia magistrate in the Senate [Pietro Grasso] and a former official of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in the Chamber [Laura Boldrini]” (1). In 2014, seventeen Grillini were elected to the European Parliament, even though the movement had long embraced the anti-EU stance of its founder, who viewed Italy’s representation in the European Union as excessively costly. In the June 2016 municipal elections, the Five Star Movement won mayoral races in Rome and Turin. Beppe Grillo’s party benefited significantly from the crisis of the Italian right, particularly the conflict that had been ongoing since 2010 between Silvio Berlusconi and his former ally Gianfranco Fini. In 2014, the exposure of a scandal involving rigged public contracts for the organization of the 2015 Milan World Expo—implicating both Berlusconi and the Democratic Party—further boosted the Five Star Movement’s popularity. In the 2018 legislative elections, it emerged as Italy’s leading party with 32% of the vote and formed a coalition government with Matteo Salvini’s League, led by Giuseppe Conte, who was close to the movement.

However, the arrival of the Five Star Movement in government marked the beginning of its decline. Indeed, inconsistencies soon became apparent: once in power, the movement did not overthrow the traditional elites. Its anti-establishment promises seemed hollow. The universal basic income promised by Beppe Grillo was implemented, but on a much smaller scale than had been claimed. As the movement’s election results declined and Conte’s government collapsed due to conflicts within the coalition, Beppe Grillo was disavowed by his base. In November 2024, his role as “guarantor” of the party was removed by a vote of the movement’s constituent assembly. Nevertheless, he continues to preach to the converted by updating his blog.

Sources

(1) "L’irrésistible ascension d’un ovni politique", Jérôme Gautheret, Le Monde, 13 mars 2017

"En Italie, la normalisation politique du Mouvement 5 étoiles", Jérôme Gautheret, Le Monde, 17 novembre 2020

"Le temps des frondeurs", Raffaele Laudani, Manière de voir, 1e avril 2021

"L’homme de la semaine : élections législatives en Italie", Philippe Ridet, Le Monde, 7 janvier 2013

"Beppe Grillo navigue sur l’impuissance de la politique", Gaël de Santis, L’Humanité, 21 mai 2014

Gianfranco Fini

Born in 1952, Gianfranco Fini kept Mussolini’s fascist legacy alive until the end of the 20th century. A journalist by training, he cut his teeth in the Youth Front, the youth wing of the Italian Social Movement (MSI), a neo-fascist party founded in 1946 by ex-leaders of the Republic of Salò, among others, and attended by former members and nostalgics of the fascist regime. The Youth Front enjoyed a certain degree of autonomy from the MSI and did not function solely as an institutional organization. Like many far-right movements, especially those made up of young people, the Youth Front used violence as a means of political action. During the Years of Lead, Youth Front militants and anti-fascist activists regularly clashed in violent and sometimes deadly encounters.

A protégé of MSI leader Giorgio Almirante, Fini rose rapidly through the Youth Front’s ranks, being appointed president by Almirante in 1977, a position he held until 1988. He was then elected secretary general of the MSI. Since 1947, the Italian Social Movement had been excluded from the “Constitutional Arc”: to keep fascism, which the MSI claimed to represent, at bay, all parties had agreed never to include it in an electoral alliance and never to allow any of its members to join the government. To come to power, the MSI had no choice but to try to expand its electorate by its own means. Convinced that, for the party to gain popularity, it needed to focus on winning over part of the Christian Democracy electorate (rather than trying to recruit communists, as some within the MSI suggested) Gianfranco Fini reoriented the party’s political line toward the center-right. This strategy proved successful a few years later, when the Christian Democrats were severely shaken by the Tangentopoli scandal, while no MSI members were targeted by corruption investigations. At the polls, the MSI gained in popularity. But the party’s allegiance to fascism and Fini’s sometimes colorful rhetoric prevented the MSI from becoming truly popular with the public. In 1989, Fini declared that he “still believed in fascism”; in 1990, he claimed that “Mussolini was the greatest statesman of the 20th century”; and, in 1994, that “Mussolini was not a criminal”. In 1993, he lost the Rome municipal elections in the second round. After this electoral defeat, Fini decided to adopt a new discursive strategy to give the MSI greater respectability. Neither fascist nor neo-fascist, he started posturing as a “post-fascist”.

Although the strategy to soften the party’s image was underway, it was not yet sufficient to completely alter public opinion. It was by collaborating with Silvio Berlusconi’s party, Forza Italia, that Fini managed to bring his party into government in 1994. At last, the “constitutional arc” was broken. Five ministers, including the vice-president of the Council of Ministers, were members of the MSI. To further reposition the party, particularly on the international stage, Fini decided in 1995 to transform the MSI into the “National Alliance”, while remaining at its head. The re-founded party removed all “archaic” fascist elements from the MSI’s political program, notably by swapping the corporatist vision of the state for market capitalism. Fini asserted that from then on, fascism would be nothing more than a historical reference and no longer the party’s ideology or objective. Under Fini’s leadership, the former MSI thus became a supposedly moderate right-wing party. A skilled tactician, he even made public appearances during which he denounced fascism, notably during a visit to Auschwitz in 1999—which did not prevent Polish anarchists from pelting him with eggs. During a diplomatic trip to Israel in 2003, he went so far as to say that Mussolini’s regime was “a shameful chapter in the history of our people” and that fascism was “absolute evil”. At the time, Fini was seeking Berlusconi’s position: with prosecutors closing in on Berlusconi, he hoped to replace him as head of the Council of Ministers if he were to resign. In the meantime, he held important positions in the Italian government and parliament. From 2001 to 2006, he was Deputy Prime Minister, a role he combined with that of Minister of Foreign Affairs from 2004 to 2006. From 2008 to 2013, he was President of the Chamber of Deputies.

In 2009, Fini and Berlusconi decided to merge the National Alliance and Forza Italia. But from 2010 onwards, Fini disapproved of Berlusconi’s policies, which he considered too closely aligned with those of the Northern League, and repeatedly called for the Prime Minister’s resignation before founding the parliamentary group Future and Freedom for Italy. However, he failed to win a seat in the 2013 elections, the first time since 1983, and withdrew from political life. In 2024, Fini was sentenced to two years and eight months in prison, a sentence he will surely not serve, after a media outlet owned by Berlusconi revealed that he had authorized the fraudulent sale of a Monegasque apartment belonging to the National Alliance to his partner’s family.

Enrico Berlinguer

Born in Sardinia on May 25, 1922, into a family of intellectuals, Enrico Berlinguer rose rapidly through the ranks of the Italian Communist Party, which he joined in 1944. In 1949, he became secretary general of the Communist Youth Federation, a position he held until 1956. He also served as president of the World Federation of Democratic Youth from 1950 to 1953. In 1956, the party’s secretary general, Palmiro Togliatti, invited him to join the PCI’s leadership group. When Luigi Longo died, he took his place at the head of the PCI in 1972.

Enrico Berlinguer is best remembered for the “historic compromise” he attempted to organize with the Christian Democrats in the 1970s. In an article published in the magazine Rinascita on September 28, 1973, entitled “Reflections on Italy after the events in Chile”, he drew the following conclusion from the assassination of Salvador Allende in Chile in 1973 and Pinochet’s coup d'état: in a world divided into two blocs, that of liberal democracy led by the United States and that of the Soviet Union, a union of the left could never come to power in Europe without being overthrown by a fascist coup organized by the CIA and networks of the Atlantic. He called on the Christian Democratic Party to “transcend partisan divisions” and form a coalition government to represent the majority of the Italian population.

Berlinguer was right to be concerned about US interference. On the one hand, there are plenty of examples of American interventionism after the war. On the other hand, Frédéric Heurtebize’s work traces the CIA’s surveillance of the PCI since the beginning of the republic, which intensified in the 1970s.

At the 14th PCI congress in Rome in March 1975, Berlinguer therefore made a formal proposal to establish an “historic compromise” with the Christian Democrats. For Aldo Moro, head of the DC, this was not without interest. While the PCI had won 27.2% of the vote in the May 1972 legislative elections, this figure rose to 34.4% in the June 1976 legislative elections. The DC would benefit greatly from the support of a party representing a third of the electorate and whose popularity was on the rise in order to remain in power. The DC had also just suffered a setback: although it had supported the repeal of the divorce law, almost 60% of the Italian population voted to retain it in the referendum of May 12, 1974, dealing a blow to the Christian Democrats’ symbolic stranglehold on political life.

On all sides, such a historic compromise was difficult to accept. DC voters feared communists’ arrival in government. Far-right movements were outraged, arguing that it was a plan by the PCI to seize power. The communist base felt betrayed, arguing that Berlinguer was abandoning his electorate to defend bourgeois democracy. As for the Americans, it is an understatement to say that they were not reassured by the possibility of communists joining a NATO government, even though Berlinguer had claimed to be distancing himself from Moscow’s policies and felt “safer” west of the Iron Curtain. Washington feared that, despite Berlinguer’s comforting words, the compromise was a Soviet Trojan horse designed not only to impose communist policies but also to gain access to NATO military secrets. During a meeting with Aldo Moro, Gerald Ford and Henry Kissinger threatened to withdraw from NATO if communists joined the Italian government.

Despite these intimidation tactics, Berlinguer and Moro worked to establish the compromise. Starting in the summer of 1976, communists in the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate stopped opposing the laws proposed by the government in order to allow them to be passed. In July 1977, a programmatic agreement signed by both parties authorized the PCI’s active participation in the development of policies defended by the DC government, except in matters of foreign policy. In January 1978, Berlinguer, strengthened by his party’s influence and aware of the DC’s dependence on the PCI, requested the appointment of Communist ministers. After his request was rejected, the party organized thousands of mass rallies to demand the entry of communists into the government. On March 9, Berlinguer secured the communists’ entry into the parliamentary majority in exchange for increased decision-making powers.

However, an event disrupted the DC and the PCI’s collaboration. On March 16, 1978, the day on which members of the PCI were to enter the government for the first time, five members of Aldo Moro’s escort were assassinated by a group of Red Brigades and the leader of the DC was held captive for 54 days. While the Red Brigades proposed negotiating a prisoner exchange for his release, the DC and the PCI chose to take a firm stance. For Berlinguer, the situation was delicate: even though the Red Brigades had no links to the PCI, their ideological affiliation with the far left led a section of public opinion to conflate the two organizations. As leader of the PCI, negotiating would be tantamount to legitimizing the violence of the Red Brigades. For their part, the DC’s representatives feared that negotiations would undermine the authority of the state—which did not prevent them, three years later, from paying a ransom to free Ciro Cirillo, another party member kidnapped by the Red Brigades in 1981. In reality, Aldo Moro’s kidnapping suited those who feared the arrival of communists in government. Indeed, this affair would put an end to the historic compromise. On May 9, 1978, Aldo Moro was found dead in the trunk of a car. The DC refused Berlinguer’s request to include communist ministers in the government.

For the first time since the beginning of the republic, the PCI lost votes in the local by-elections of May 14, 1978, winning only 26.5% of the vote. In January 1979, under pressure from metalworkers who wanted to organize a general strike, the PCI withdrew its support for the Andreotti government in both houses and once again became the leading opposition party. At this point, Berlinguer felt that the government was not consulting the party sufficiently. In its reports, the CIA welcomed the decline of his party in the 1979 legislative elections and the 1980 regional elections. Faced with the hostility of Bettino Craxi’s Socialist Party to an alliance with the PCI, Berlinguer reinvested in his working-class electorate by supporting the strikes at the Fiat factories.

For Berlinguer, the historic compromise was part of a broader political movement that he had initiated: Eurocommunism. According to historian Frédéric Heurtebize, this “political phenomenon, largely forgotten today”, nevertheless constituted a major development for the Italian and, to a lesser extent, French communist parties because it marked a distancing from the Soviet Union and an effort to reconcile communist principles, democratic principles, and capitalist societies. This was not the first time that the PCI had asserted its autonomy from Moscow. In 1956, Palmiro Togliatti, Berlinguer’s predecessor as party leader, called for the development of an “Italian path to socialism”, and in 1968, the PCI denounced the repression of the Prague Spring by communist tanks.

But under Berlinguer’s leadership, the PCI moved closer to other communist parties west of the Iron Curtain. In July 1975, he met with the national secretary of the PCE, Santiago Carrillo, and in September of the same year, with the national secretary of the PCF, Georges Marchais. In March 1977, the three men met in Madrid to reaffirm their autonomy from Soviet communism. But differences of opinion between the PCF and the PCI, particularly on economic and foreign policy (unlike the PCF, the PCI was in favor of European integration) and their differences in political weight (the PCI was more influential) in addition to the failure of the historic compromise that was the spearhead of Eurocommunist policy, contributed to the failure of Eurocommunist sentiment.

Despite the interruption of the historic compromise and the failure of Western communism to integrate at the European level, Berlinguer profoundly changed communist political practice by reconciling it with the operations of Italian democracy. Under his leadership, the PCI won numerous electoral victories and thus represented about one-third of the population. While campaigning for the 1984 European elections, he died of a cerebral hemorrhage during a public speech on June 11, 1984. Tragically, he did not live to see the PCI win 34% of the vote just a few days later. His death marked the beginning of the party’s decline: his successors found it increasingly difficult to avoid the general crisis of communism in Europe.

Sources

"Enrico Berlinguer", Encyclopédie Universalis, Geneviève Bibes.

Les Transitions italiennes. De Mussolini à Berlusconi, Philippe Foro, L’Harmattan, 2004.

"Washington face à la participation des communistes au gouvernement en Italie (1973-1979)", Frédéric Heurtebize, Vingtième siècle. Revue d’histoire, 2014/1 n°121, 95-111.

Le péril rouge. Washington face à l’eurocommunisme, Frédéric Heurtebize, Presses Universitaires de France, 2014.

Kyle Rittenhouse

A man “whose sole qualification is killing people standing up for Black lives and getting away with it”. That’s how Cori Bush, then Democratic U.S. Representative for Missouri, described Kyle Rittenhouse in 2021. The young murderer had just been found not guilty in his trial for voluntary manslaughter, attempted manslaughter, and reckless endangerment. On August 25, 2020, Rittenhouse shot and killed two people in the town of Kenosha, Wisconsin: Joseph Rosenbaum and Anthony Huber, two demonstrators who had come to protest the murder of Jacob Blake by a local police officer. Rittenhouse then wounded a third man, Gaige Grosskreutz, who was trying to stop the killing by pointing a handgun at him. Even though his first two victims were unarmed - except for a skateboard in Huber's case - and he was in possession of an AR-15 semi-automatic rifle, Rittenhouse, who would soon become a MAGA darling, was acquitted on grounds of self-defence.

At the time of the shooting, Rittenhouse was 17 years old. He traveled from Antioch, Illinois, to act as a vigilante in Kenosha. His goal, he would later explain during his trial, was to prevent anti-racist organizers from threatening the safety and property of honest business owners. Parading through the streets with his loaded rifle, he fired when Rosenbaum, Huber, and Grosskreutz successively tried to disarm him.

During the trial, and even more so after his acquittal, both the right-wing media and neo-fascist organizations, as well as elected Republicans and their base, treated Rittenhouse as a hero — two-thirds of Donald Trump voters saw him as an example of patriotism. He was interviewed twice by the famous columnist Tucker Carlson, who was still on FOX News at the time and who reached one of his largest audience by interviewing him; the Proud Boys, one of the leading far-right organizations, made him their mascot; he was offered numerous jobs and internships — both by the gun lobby and by MAGA senators and congressmen — and was even received, with his mother, by the former and future president at his Mar-a-Lago lair in November 2021.

After an unsuccessful attempt at publishing video games based on his exploits, Rittenhouse gradually withdrew from the spotlight, even though the Texas chapter of the National Association for Gun Rights continues to call on his services and Turning Point, the libertarian association headed by Charlie Kirk, persists in organizing events where he is presented as America's ideal son-in-law. This is because, as Cori Bush pointed out, shooting unarmed protesters is really his only qualification.

On the other hand, Rittenhouse's hour of glory remains an important reminder to anyone who doubts that murderous hatred is indeed the most powerful driving force behind the MAGA movement.

Moshe Dayan

For anyone who came of age during the Cold War, and particularly among supporters of Israel, Moshe Dayan (1915–1981) is an iconic figure. One of the first prominent Israeli politicians to be born in Palestine, he joined the Haganah, the Zionist paramilitary organization, at the age of 14, before enlisting in the British Army during World War II. From the declaration of independence in 1948 until his death in 1981, Moshe Dayan held numerous positions in the army and government: he was Chief of Staff from 1955 to 1958, Minister of Agriculture in the early 1960s, Minister of Defense in the governments of Levi Eshkol during the Six-Day War and Golda Meir during the Yom Kippur War, and finally Menachem Begin’s Minister of Foreign Affairs between 1977 and 1979, at the time of the peace negotiations with Egypt.

A fervent supporter of the occupation of the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza, Dayan campaigned after 1967 for a dual strategy of quelling resistance while integrating Palestinians into the Israeli economy, notably through the widespread distribution of work permits.

Moshe Dayan's name has recently returned to the headlines because of a famous eulogy: On April 30, 1956, the then chief of staff of the army visited the Nahal Oz kibbutz on the Gaza Strip border to pay tribute to Ro'i Rothberg, a kibbutznik killed the day before by Palestinian refugees who had returned to the place from which they had been expelled eight years earlier.

Moshe Dayan's speech remains famous in Israel, mainly because it called on Israelis never to let their guard down. However, it is the fact that the Nahal Oz kibbutz was one of the places most violently attacked by Hamas militants on October 7, 2023, that has brought it back into the spotlight. For advocates of Israeli “reprisals,” Moshe Dayan's call for uncompromising firmness in 1956 is more relevant than ever today. But critics of the ongoing destruction of Gaza focus on two other aspects of the famous general's speech.

First, they recall that when Moshe Dayan took the floor at Nahal Oz, he began his speech as follows: “Yesterday morning, Ro'i was murdered. Intoxicated by the serenity of dawn, he did not see those who were waiting for him in ambush at the edge of the plowed field. But let us not cast shame on his murderers. Why blame them for the burning hatred they feel toward us? For eight years they have lived in the refugee camps of Gaza, while before their very eyes we have made our own the land and villages where they and their ancestors lived. It is not the Arabs of Gaza we should ask to account for Ro'i's blood, but ourselves. How could we have closed our eyes and refused to face our destiny and the mission of our generation, in all its cruelty?”

Second, as historian Omer Bartov points out, Moshe Dayan’s lucidity proved short-lived. For when he recorded his eulogy for Israeli radio the next day, there was no trace of the passage about the refugees and their good reasons for rejecting the settlers rule1.

1Omer Bartov, As a former IDF soldier and historian of genocide, I was deeply disturbed by my recent visit to Israel, The Guardian, 13 August 2024

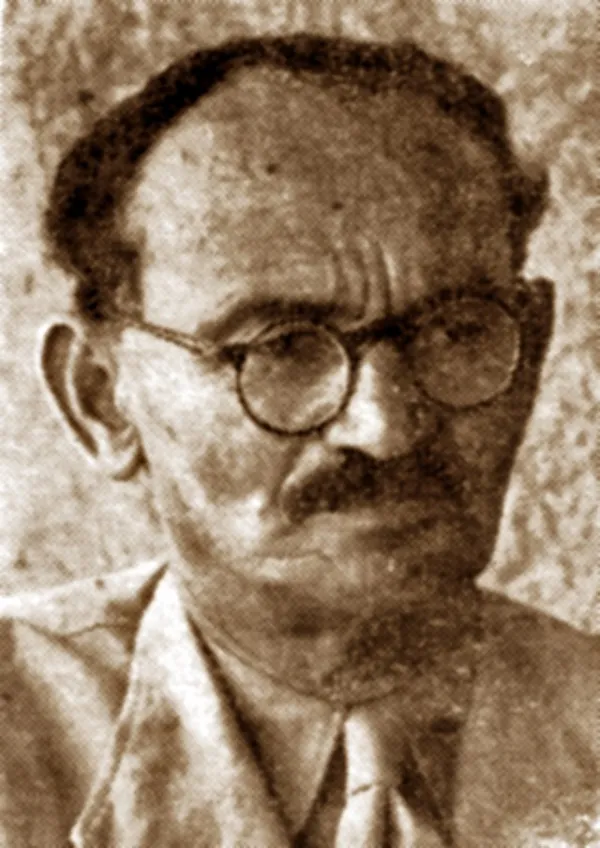

Yosef Weitz

Yosef Weitz (1890-1972) was one of Modern Israel’s founding fathers, emigrating from present-day Ukraine in 1908 to champion the Zionist cause, becoming director of the Land and Afforestation Department of the Jewish National Fund (JNF) during the Mandatory Period.

He had a notorious role in the frantic expropriation of Palestinian lands, and in consolidating the war’s spoils over decades through agriculture and arboriculture. He thereby implemented Israel’s founding prime minister David Ben Gurion’s call to “make the desert bloom”, all the while uprooting hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from their lands. The Ottoman property laws, taken up by the British mandate and then by the Israeli occupation, were employed to legitimize, through its cultivation, colonial ownership of the land seized from the local population.

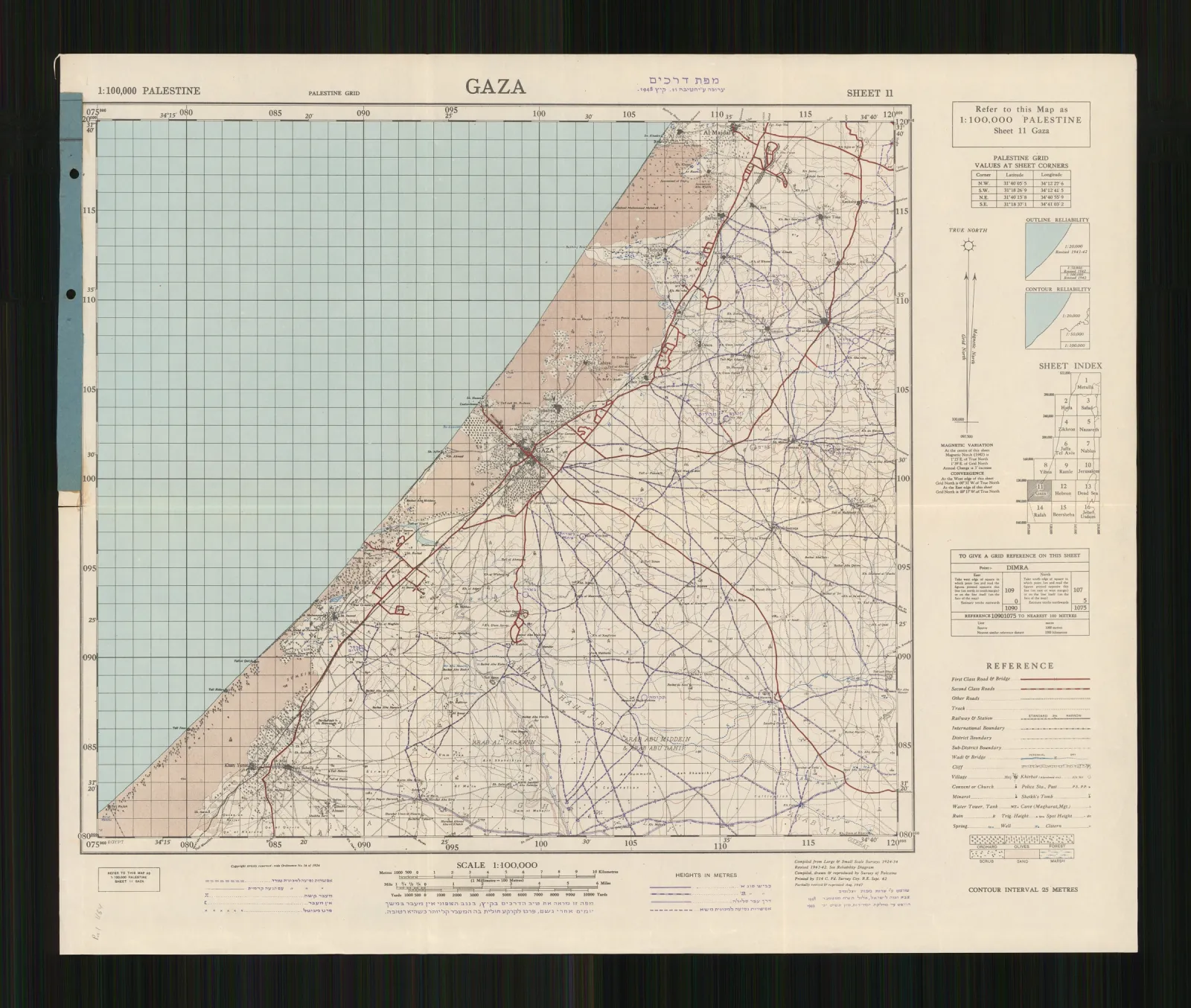

Timelines

1949

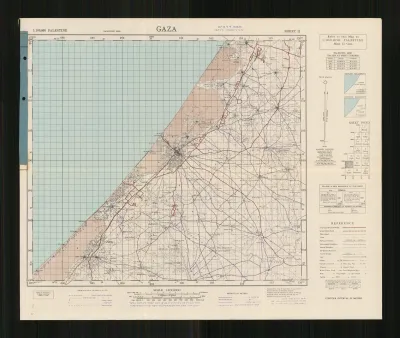

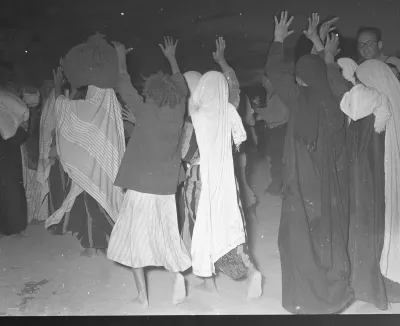

Creation of the Gaza Strip: The armistice signed between Israel and Egypt in February 1949 put the 555 square kilometers area henceforth known as the Gaza Strip under Egyptian control. Out of the 750,000 Palestinians expelled from their homes during the Nakba (the catastrophe), 200,000 were forced to resettle in Gaza, many of them in refugee camps.

1953

Attack of al-Bureij camp. In 1953, Moshe Dayan, the newly appointed IDF chief of staff, created Unit 101, a commando unit whose mission was to eliminate “infiltrators”, i.e., refugees trying to return to their homes. On August 28 of that year, a patrol of Unit 101 led by Ariel Sharon entered the al-Bureij camp in the Gaza Strip and killed up to 50 civilians in what was framed as a preventive mission against further infiltrations.

1956

Khan Yunis and Rafah massacres. During the Suez campaign, the IDF briefly occupied Gaza as part of a combined attempt by Israel, France and Britain to occupy the Sinai, topple Gamal Abdel Nasser and reopen the Suez Canal. During their incursion, Israeli soldiers rounded up and killed hundreds of men, first in the Khan Younis refugee camp, on November 3, and nine days later in the city of Rafah.

1967

Occupation of Gaza. Israel occupied the Gaza Strip, as well as the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights in June 1967. Dubbed the Naksa (the setback), the conquest of these territories was followed by what Palestinians remember as the “Four Year War”. Ariel Sharon, then head of Israel's Southern Command, orchestrated the division of the Strip into zones, the deportation of thousands of Gazans and the destruction of several refugee camps in order to quell the resistance.

1987

First Intifada. The First Intifada started in Gaza, on December 8, 1987: a riot erupted in the Jabalia refugee camp after an Israeli vehicle caused a crash that killed four Palestinians. The upheaval would rapidly spread to the rest of the Strip and the West Bank. Violently repressed by Israeli forces, the Intifada lasted six years, during which a hundred Israelis and a thousand Palestinians were killed.

1996

The Iron Wall. One year after the signing of the Oslo I Accord, the Israeli authorities sought to tighten their control over the allegedly autonomous Gaza strip by erecting a barrier called the Iron Wall. Fully erected by 1996, this construction has played a crucial role in the isolation and de-development of Gaza.

2004

Second Intifada. During the Second Intifada (September 2000-February 2005), Israeli forces launched a number of retaliatory raids in Gaza: “Operation Rainbow”, in May 2004, involved the murder of more than 50 Palestinians, including children, and the destruction of three hundred homes in Rafah, whereas “Operation Forward Shield”, in August, and “Operation Days of Penitence”, in October, killed at least 134 Palestinians in the towns of Beit Hanoun and Beit Lahia.

2008/9

The First Gaza War. In December 2008, Israel broke what had been a fragile ceasefire with Hamas by launching “Operation Cast Lead”: combining air strikes, naval operations and ground invasions, the mission lasted until the end of January 2009 and killed about 1,400 Palestinians and injured 5,300 in Gaza City, Rafah, and elsewhere in the Strip. Particularly brutal was the Zeitoun District Massacre: entire neighborhoods were razed, creating about 100,000 refugees, whilst white phosphorus munitions were used on civilian populations in densely-populated residential areas.

2012

Operation Pillar of Defense. Starting with the assassination of Ahmed Jabari, chief of the Hamas military wing in Gaza, Israel launched “Operation Pillar of Defense” in November 2012: the maneuver destroyed settlements all over the Gaza strip, killing 171 Palestinians, including 102 civilians, in the span of 8 days, and displacing 700 families.

2014

Battle of the Withered Grain. In order to dissuade Hamas from firing rockets from Gaza, Israel conducted a seven-week-long operation, dubbed “Protective Edge”: ground and air forces launched about 50,000 shells onto the Strip, in a combination of bombs, tank missiles, and other artillery. About 2,200 Gazans were killed including 1543 civilians and 10,000 wounded.

2018/9

The Great March of Return. From March 2018 to December 2019, Gazan civilians, eventually backed by Hamas, demonstrated peacefully every Friday to claim their “right of return” and protested the blockade imposed on the Strip. Israeli soldiers systematically responded with deadly force, killing 214 demonstrators and over 36,000 injured in the course of 21 months.

2021

Unity Intifada. The so-called Unity Intifada was triggered by an Israeli Supreme Court decision, in May 2021, ordering the eviction of four Palestinian families from East Jerusalem. Violence escalated after the Israeli police stormed the Al-Aqsa Mosque and Hamas and Islamic Jihad retaliated by launching rockets from Gaza. In response, the IDF conducted a two-week operation “Guardian of the Walls”, which killed 260 people, destroyed about a thousand housing units and resulted in the internal displacement of more than 70,000 Palestinians, in what Tsahal described as the “first artificial intelligence war”. Journalists were targeted in the shelling of the al-Jalaa Tower, which housed Al Jazeera, Associated Press, and several other media.

2022

Operation Breaking Dawn. In August, 2022, then Prime Minister Yair Lapid and Defense Minister Benny Gantz ordered “Operation Breaking Dawn” in retaliation for ongoing rocket attacks by Hamas and Islamic Jihad: it involved some 147 airstrikes and killed about 50 civilians in Gaza City, Rafah, Khan Yunis, Beit Hanoun, and Jabalia. “Breaking Dawn” was the last operation of its kind before the ongoing genocidal campaign.

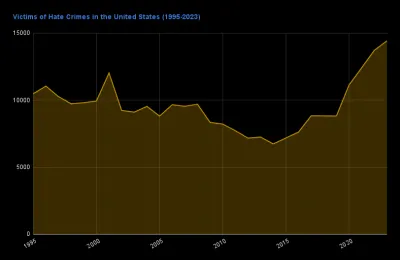

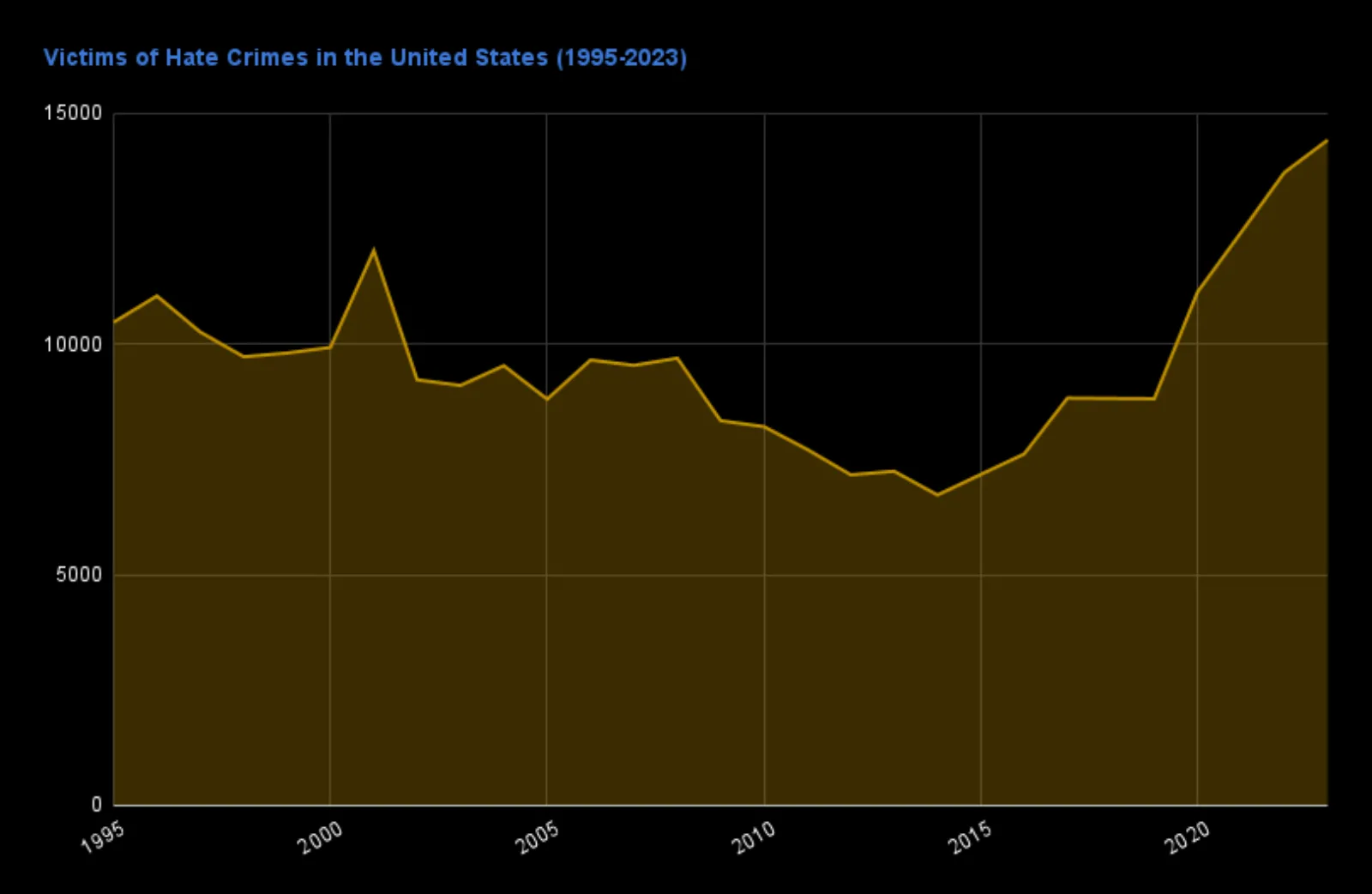

2015-2023

It took nineteen years for the number of victims of hate crime in the United States to drop by 36%. In 2014, it reached its lowest since the 1990s. In only nine years, that number went back up 115%.

Many researchers, including Griffin Sims Edwards and Stephen Rushkin, have documented the impact of Donald Trump’s hate speech, and the legitimacy it acquired after his victory, on the rise of domestic terrorism since 2015. Here are a few examples of what they’ve termed, “the Trump effect”.

June 17, 2015

Dylann Roof, a 21-year-old white supremacist and self-proclaimed neo-Nazi, opened fire on the Black community of Mother Emanuel Church in Charleston, South Carolina. He had attended an hour-long Bible study class at the religious establishment before gunning down nine of its participants. “I almost didn’t go through with it because everyone was so nice to me,” he told the police, but the man was determined to start a race war. Radicalized online after spending hours reading the Council of Conservative Citizens’ racist diatribes, Roof, a native of South Carolina, bitterly regretted the good old days of the Confederate States for whom “slavery subordination to the superior race is [the] natural and normal condition [of the negro]”. The day after the massacre, all flags were lowered to half-mast, and only the Confederate flag, with which Roof loved to take photos, continued to fly proudly over the Capitol in Columbia.

August 11-12, 2017

In Charlottesville, Virginia, hundreds of white supremacists, neo-Confederates, neo-fascists, neo-Nazis, members of the alt-right, the Ku Klux Klan, and far-right militias gathered to protest the city's decision to remove the statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee from a park. The “Unite the Right rally”, which aimed to unify the American white nationalist movement, was met with resistance from numerous anti-fascist activists. On August 12, neo-Nazi James Alex Fields Jr. drove his car into a group of counter-demonstrators, injuring 35 and killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer. Far from condemning the rally and the hateful motivations of its initiators, Donald Trump established an equivalence between the neo-fascists and anti-fascists clashing in Charlottesville, declaring that “there are very fine people on both sides”.

August 3, 2019

In El Paso, Texas, on the U.S.-Mexico border, Patrick Crusius committed one of the deadliest mass murders on U.S. soil since World War II. Stating that he wanted to kill as many Mexicans as possible, he opened fire at a Walmart store, killing 23 people and wounding just as many. Prior to the shooting, Crusius was obsessed with the immigration debate. Praising Donald Trump's hardline border policy on social networks, everything in the manifesto he wrote to denounce the “Hispanic invasion” echoed the president's rhetoric on Mexican immigration. Three months earlier, at a rally in Florida, Trump had asked his supporters for ideas on how to “stop these people”. One of his supporters had shouted “Shoot them!”. The crowd laughed, the president smiled.

May 14, 2022

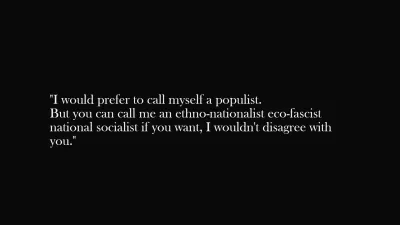

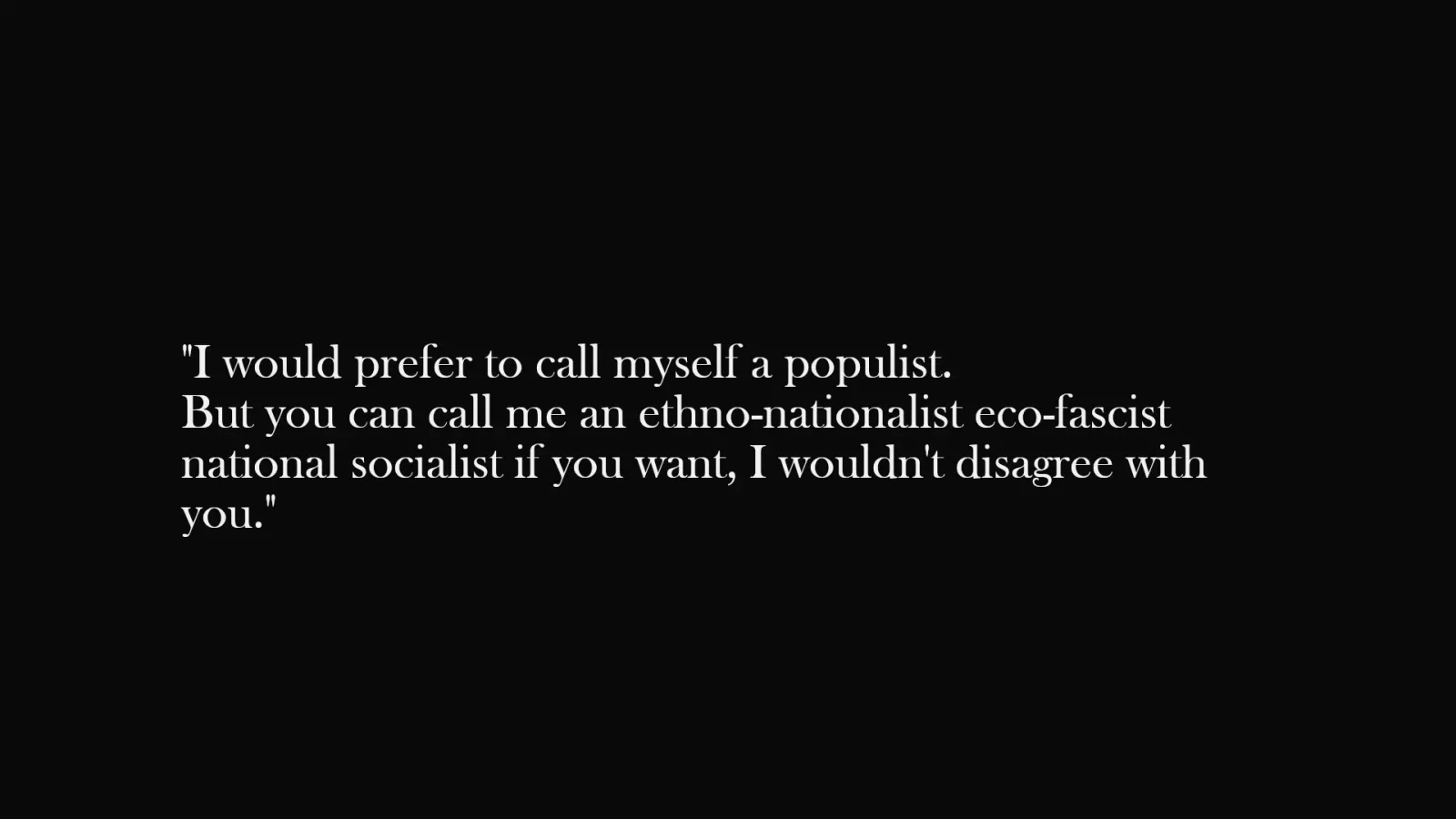

Payton Gendron, a proponent of the “Great Replacement” theory and self-described ethno-nationalist and white supremacist, was eighteen years old when he killed ten people, all of whom were Black, and wounded three others in a grocery store in Buffalo, New York. With this act, he hoped to “terrorize all non-white and non-Christian people, and drive them out of the country”. In the manifesto he published online before the attack, Gendron said he initially identified as left-wing, before being convinced by the populist, supremacist, anti-Semitic, and ecofascist ideological positions of Neo-Nazi Andrew Anglin. Anglin was one of Donald Trump’s earliest supporters in 2015, calling on his readers to follow him. He wrote, “let's vote for the first time in our lives for the only man who truly represents our interests.”

May 6, 2023

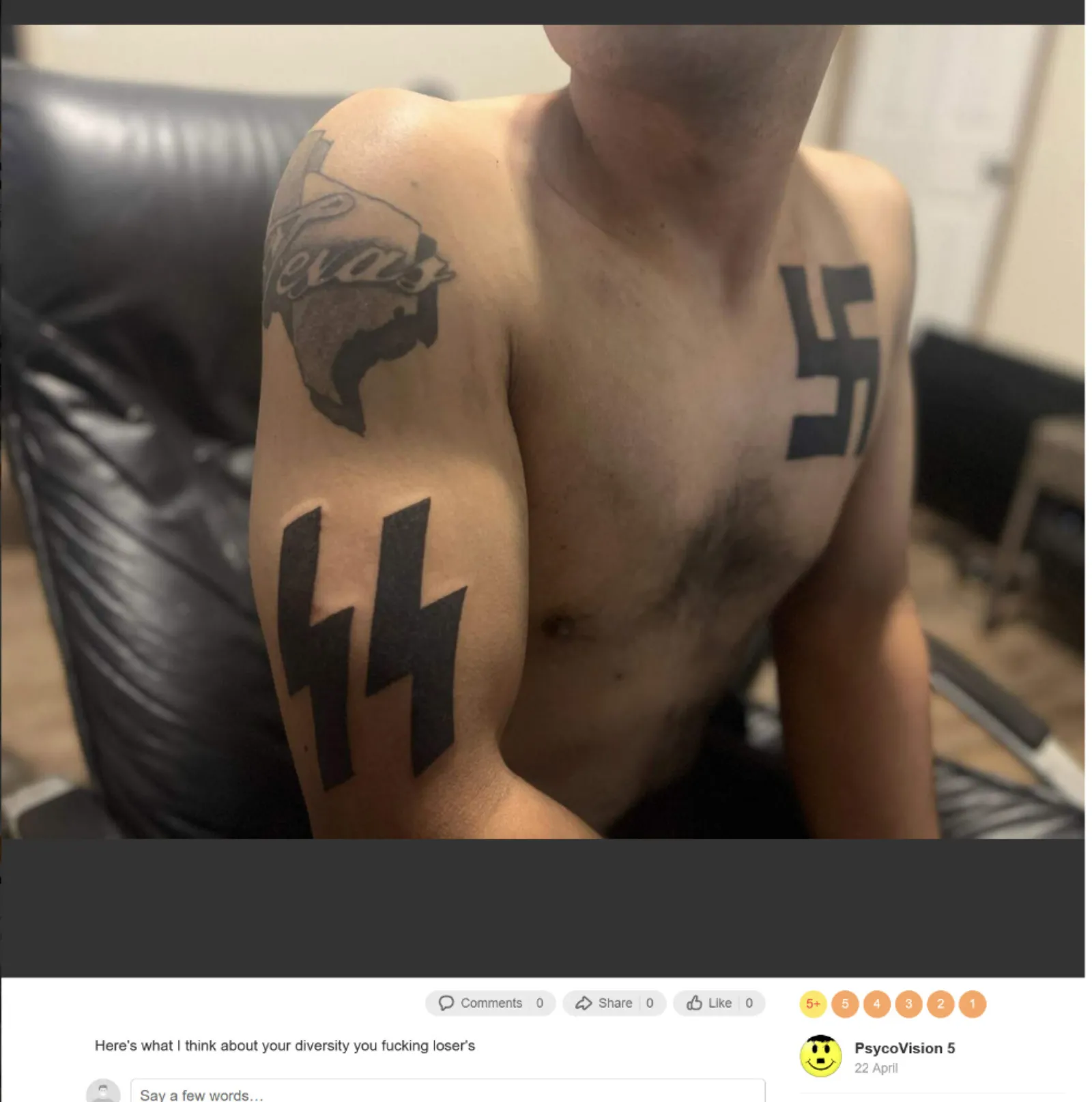

Mauricio Martinez Garcia is a Neo-Nazi, a (non-white) white supremacist, and an incel who killed eight people, including a three-year-old asian boy, in a shopping center in Allen, Texas. During the shooting, he wore a tactical vest embroidered with an “RWDS” (Right Wing Death Squad) crest. On his profile on the Russian social network Odnoklassniki, Garcia posted photos of his fascist tattoos, expressed his hatred of Asians, Arabs, Jews, and women, and fantasized about race wars and the collapse of society as a whole.

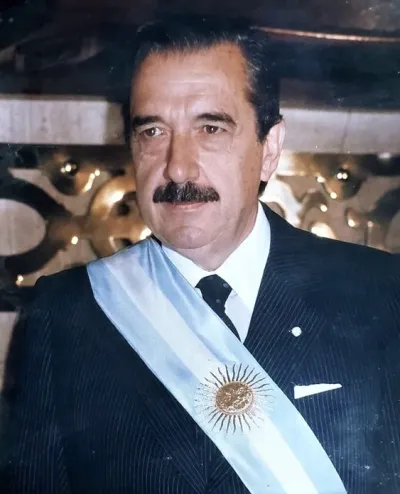

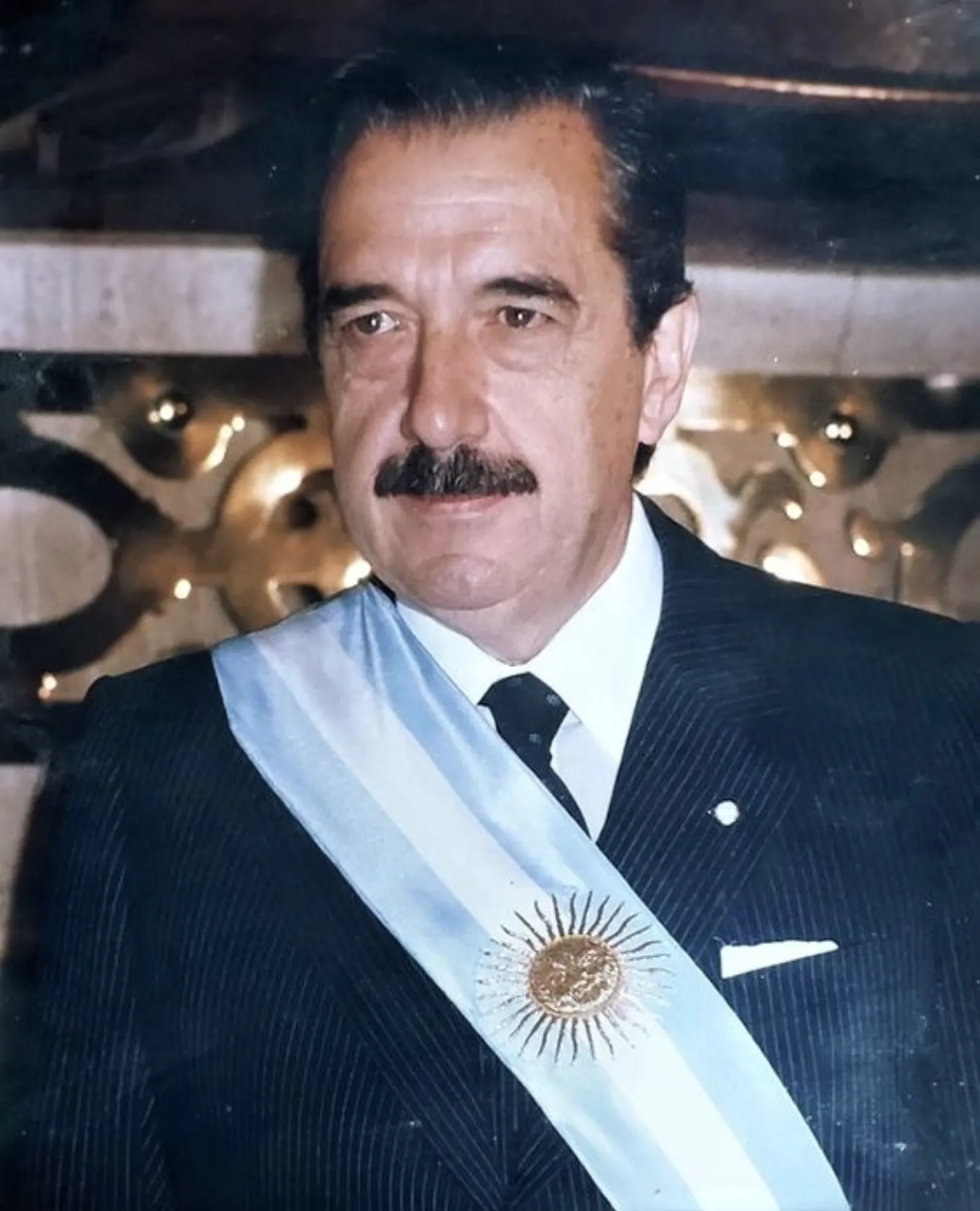

December 1983 - July 1989

Raúl Alfonsín

Candidate of the social-democratic Radical Civic Union (UCR) in the 1983 election, Raúl Alfonsín’s presidency marked Argentina’s return to democracy after decades of military rule interspaced by periods of Peronist domination. Shortly after taking office, he set up the first official inquiry into the dictatorship’s crimes, the CONADEP (National Commission on Disappeared Persons). As opposition leader, he later signed the Pact of Olivos, a memorandum of understanding for a constitutional reform allowing his successor Carlos Menem to be reelected in 1995.

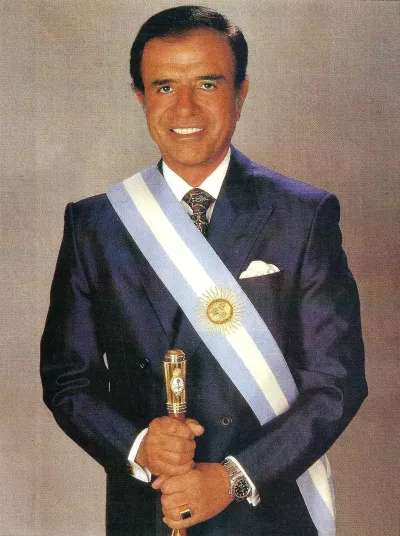

July 1989 - December 1999

Carlos Menem

Peronist Carlos Menem came to power in 1989, in a context of hyperinflation and social unrest, aiming to promote a newfound national stability. He immediately implemented neoliberal structural reforms and sweeping privatisations along the precepts of the Washington Consensus, and pegged the Argentine peso to the US dollar. Menem was re-elected in 1995, but his monetary and trade policies plunged his country into recession by the end of this second mandate. He also pardoned military and police commanders of the “Dirty War” period, responsible for killing thousands of civilians.

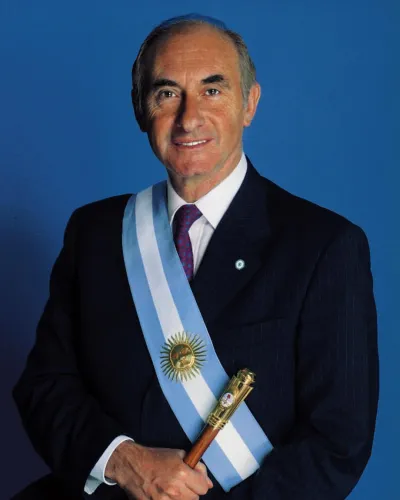

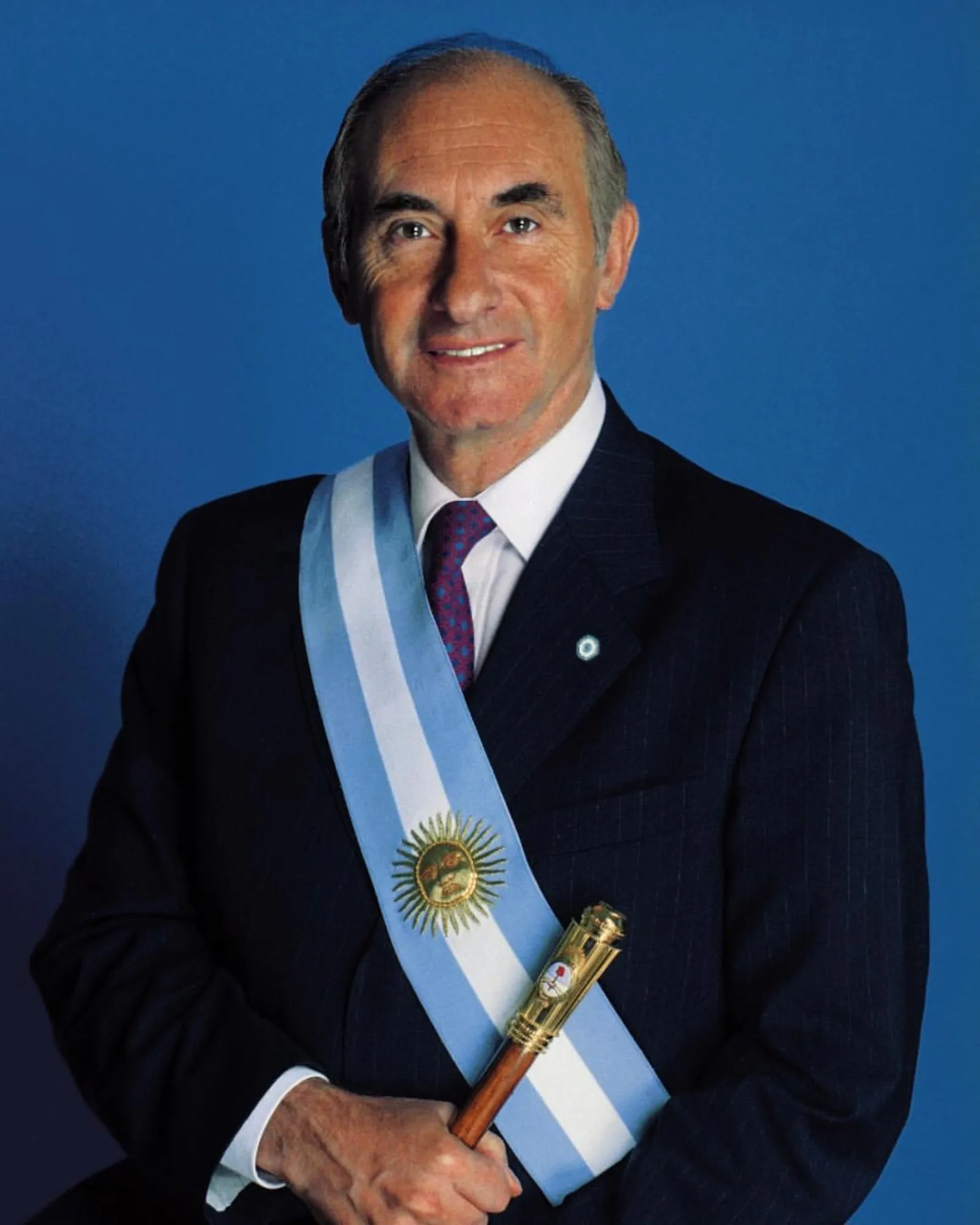

December 1999- December 2001

Fernando de la Rúa

Menem’s short-lived successor, mayor of Buenos Aires Fernando de la Rúa, could not reverse Argentina’s downward trend at the turn of the century. He called a state of emergency in December 2001, enforcing the “corralito”, a limit on cash withdrawals. In the midst of this full-blown banking and currency crisis, massive popular protests erupted. Eventually, grassroots opposition movements initiated among others by the piqueteros forced him to resign. He famously fled from the presidential Casa Rosada in a helicopter.

May 2003 - December 2007

Néstor Kirchner

Following the ‘Great Depression’, under the two interim presidencies of Adolfo Rodríguez Saá and Eduardo Duhalde, Néstor Kirchner came to power in 2003, aiming to bolster the Peronist Justicialist Party’s support among the working class. He managed to stitch together a broad, consensual coalition on a platform of economic growth, moderate redistribution, human rights justice, and restored sectoral collective bargaining. His relative success in some of these areas made him a symbolic figure of the Latin American “Pink Tide” of the early 2000s, albeit without him ever truly tackling the structures of capital accumulation.

December 2007 - December 2015

Cristina Fernández de Kirchner

Cristina Fernández de Kirchner succeeded her husband, initially aiming to build on his progressive policies with nationalisations, energy prices subsidies, currency controls, and the introduction of a Universal Child Allowance program. Going into her second mandate, however, she went down the path of fiscal austerity, passing a series of controversial measures dubbed sintonía fina [fine tuning]. By the end of her term, Kirchner faced major protests in a context of stagnating wages, growing inflation and corruption scandals.

December 2015 - December 2019

Mauricio Macri

Amidst intense polarization between Kirchner’s supporters and opponents, known as la grieta [the crack], the millionaire businessman Mauricio Macri was elected in 2015. Macri formed a conservative-reformist centre-right coalition, Cambiemos, with which he was able to reverse many of Kirchner's policies through liberalization, deregulation, drastic cuts to public spending, His allegedly meritocratic agenda did not improve either unemployment or inflation, however. Soon confronted with a severe monetary crisis, Macri signed on to a $57 billion IMF loan – the biggest in the organisation’s history. In 2023, he stood openly behind Milei’s candidacy. Many cadres of the new far-right libertarian government hail from his traditional conservative party, Republican Proposal.

December 2019 - December 2023

Alberto Fernández

Alberto Fernández was Chief of the Cabinet of Ministers under the two Kirchner administrations until his resignation in 2008, He defeated incumbent Macri in the 2019 election. Fernandez had in the meantime reconciled with former president Cristina Kirchner, who had become too unpopular to run herself, but provided crucial support for his ticket and then served as a discreet vice-president. Fernández’s term was marked by the Covid-19 crisis and its socio-economic consequences, and by a continued degradation of living standards and soaring inflation levels, leading many disoriented voters, especially young ones, to cast their vote on Milei in 2023.

1979

Ten days after the start of the hostage crisis at the US Embassy in Tehran, President Jimmy Carter issued Executive Order 12170, which imposed the seizure of all Iranian government assets held in the US, freezing more than $8 billion in bank deposits, gold reserves, and other assets. A trade embargo was also imposed. This measure was lifted in January 1981, as part of the Algiers Accords, which constituted a negotiated settlement in exchange for the release of the hostages. Diplomatic relations between the two countries had been formally suspended since April 1980.

1983

Sanctions were extended to the military sphere in the context of the Iran-Iraq War (1981-1988). Ronald Reagan launched Operation Staunch, which imposed an arms embargo, including on American-made spare parts. The Iran-Contra affair revealed that arms sales had secretly continued, via Israel, with the dual purpose of securing the release of seven American hostages held in Lebanon and generating a budget surplus to supply military equipment to the Nicaraguan Contra insurgents, who Regan supported.

1995-1996

In 1995, Bill Clinton prohibited American companies from supervising, managing, and financing the exploitation of oil resources located in Iran. His administration once again blocked all commercial activity between the two countries. The following year, the US Congress passed the Amato-Kennedy Act, which was intended to put an end to the acquisition of weapons of mass destruction and support for terrorism by Iran and Libya. The various sanctions included in the law also applied to international economic operators. Two years later, following a compromise negotiated with the EU, European companies were temporarily exempted from these sanctions. Following the election of reformist Mohammad Khatami in 1997, some of these measures were also relaxed.

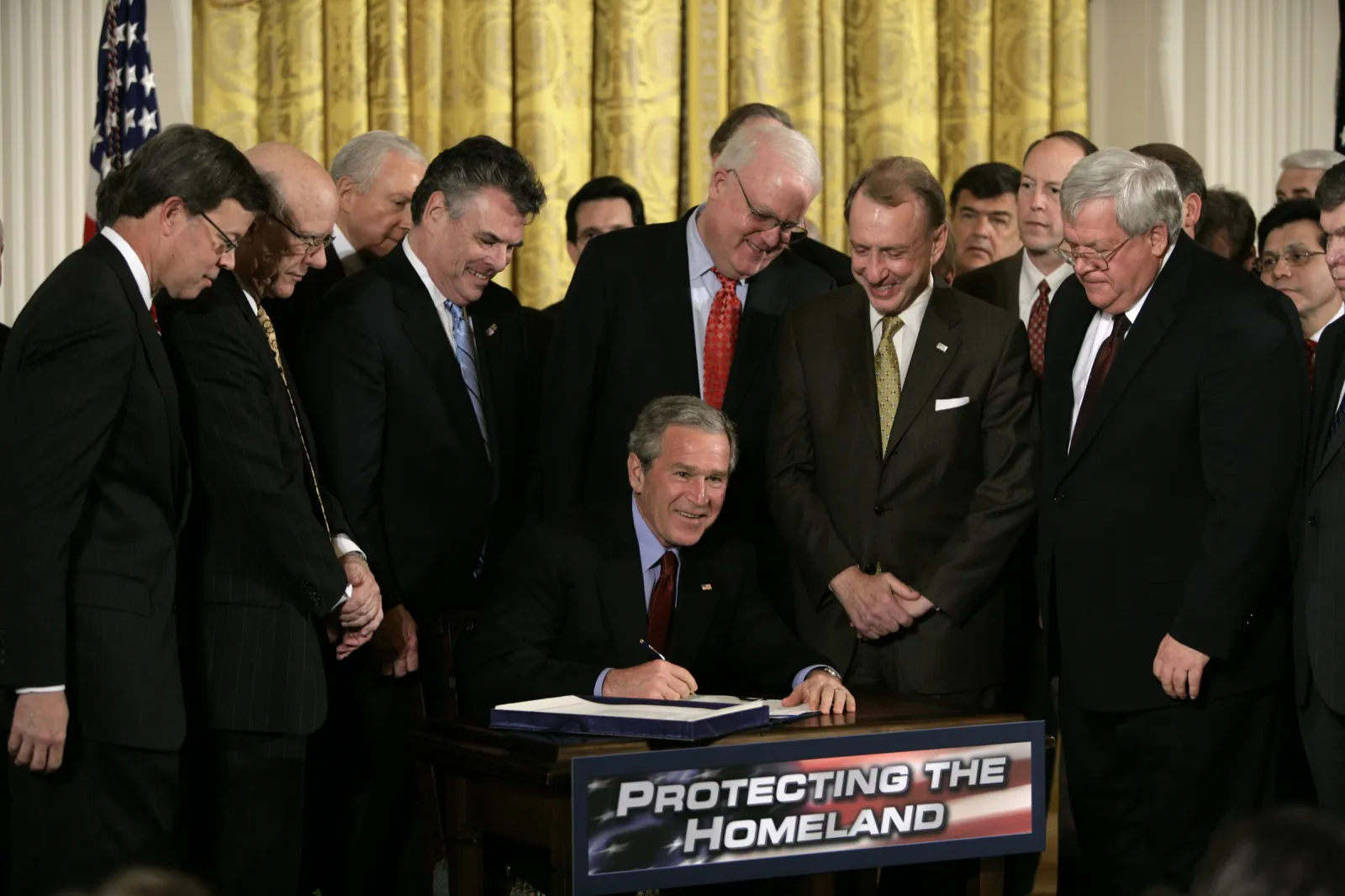

2004-2006

G.W. Bush imposed sanctions on Iranian scientific publications in order to hinder nuclear engineering research. A new Executive Order also froze the assets of individuals linked to Iran’s nuclear program. The country’s banking institutions were then denied direct access to the US financial system. A list of undesirable individuals and entities was drawn up by the Treasury. These were added to the automated filtering systems used by many international banks and may also have been subjected to sanctions under the Patriot Act.

2010-2014

Barack Obama further tightened the screws by ratifying the Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act, passed by Congress. This was a measure aimed at strengthening economic restrictions against Iran, notably by banning imports of various Iranian products, and through another package of financial sanctions, imposing record fines of several billion dollars on certain major European banking institutions.

2018-2019

Donald Trump imposed a series of measures with an explicit title: the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act. The sanctions, lifted under the nuclear agreement signed in Vienna in 2015, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), were also reintroduced. Chinese, British, and Emirati investors were severely penalized for their activities in Iran. Through the Treasury, the White House blocked transactions with the Iranian iron, steel, aluminum, and copper sectors and directly targeted Supreme Leader Khamenei and his entourage, including judges and Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif.

2021-2024

The return to power of the Democratic administration did not lead to the lifting of Trump’s sanctions. On the contrary, the Biden administration used the crackdown on protests following the death of Mahsa Amini as a pretext to introduce new measures targeting the country’s security organization, such as the Morality Police. Other sanctions were presented as solutions to the development of Iran’s ballistic program.

2025

At the dawn of his second term, Trump came back with a vengeance, promising a campaign of “maximum pressure” on Iran. He renewed a wave of sanctions against Tehran’s military-industrial complex, taking shock actions against prominent figures, extending the list of undesirable institutions, and making a particular effort to torpedo Sino-Iranian trade.

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter

Because resisting the world's rightward drift starts with taking the measure of it